-

The Emperor in the war year 1914, propaganda postcard

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H.

Partner: Schloss Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. -

Emperor Franz Joseph: “To my peoples”, special edition of the Official Gazette of the Imperial-Royal Capital and Residence City Vienna, No. 61, 23rd year (29 July 1914)

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H.

Partner: Schloss Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H.

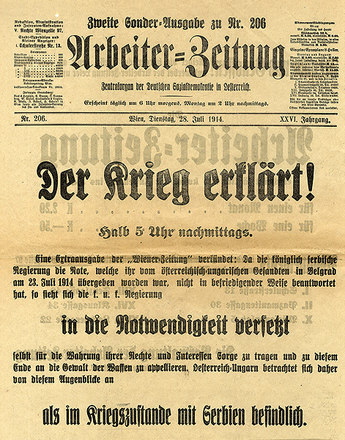

On 27 July 1914 the Austrian foreign minister Berchtold requested Emperor Franz Joseph to sign the declaration of war, on the express grounds that the situation called for swift action, in order to achieve a fait accompli that would forestall any possible peace initiative on the part of the Triple Entente.

At the same moment news arrived of an exchange of fire between Austrian and Serbian units on the Serbian border, which was immediately communicated to Franz Joseph at his summer residence in Bad Ischl. Under the impression that there had been a Serbian act of aggression he signed the declaration of war that very same day, 27 July, including a reference to the exchange of fire that was supposed to have taken place. On the morning of 28 July, however, it became known that the news had been erroneous – possibly deliberately erroneous – and that Serbia had not committed any act of aggression. Thereupon Foreign Minister Berchtold published the declaration signed by the Emperor but with the relevant passage deleted. However, it was not until the following day, 29 July, that Franz Joseph was informed that the news from the border had been a false alarm.

Austria-Hungary’s official declaration of war on Serbia of 28 July resulted in a catastrophic chain reaction. The escalation began. On 30 July general mobilization was ordered in Russia. The following day the same order was given in Austria-Hungary. The wheels of war started to turn.

On 1 August, Germany announced that it was at war with Russia, after having demanded the reversal of the Russian general mobilization in an ultimatum that was immediately rejected by the foreign minister in St Petersburg. A few days later, on 3 August, buoyed up on a wave of enthusiasm for war, Berlin finally also declared war on France and invaded Belgium, as a result of which 4 August saw Great Britain declaring war on Germany. Berlin’s hopes of Britain remaining neutral were now shattered for good.

The Danube Monarchy was also sucked into the maelstrom of escalation after declaring war on Russia on 6 August: as a result, on 12 August Great Britain and France declared war on Austria-Hungary.

The whole development was made even more complicated when further states such as Belgium, a number of Balkan states and the Ottoman Empire sided with one or other of the two power blocks. At the end of August 1914 the conflict acquired a global character when Japan entered the war as an opponent of the Central Powers.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg. Aktualisierte und erweiterte Studienausgabe, Paderborn/Wien [u.a.] 2009

Leidinger Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien [u.a.] 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013