‘If the Monarchy is to go, then at least it should go with honour.’ This saying attributed to Franz Joseph is often quoted as being symptomatic of the general exhaustion of the traditional elites of the Habsburg monarchy.

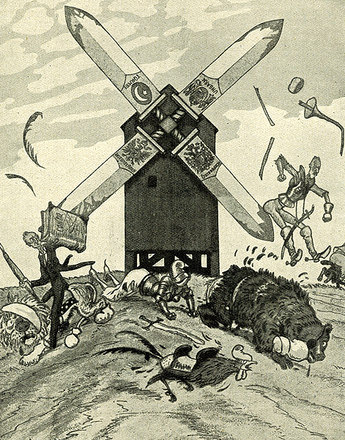

Austria-Hungary’s political leaders found themselves on the horns of a dilemma. Internationally, they were expected to react to the shots fired in Sarajevo; if Austria-Hungary was to avoid becoming a passive player amongst the great powers, it had to make a show of activity, even though those in the corridors of power were fully aware of their own weakness. The fact that they went with eyes open and heads held high into the abyss of destruction is a sign of the callousness of the weary elites of the ancient imperial polity – and even of a kind of death-wish on their part.

The perception of the war as a final struggle destined to determine the future resulted in an apocalyptic mood of another kind. In a debased form of the social Darwinism rampant in the media and the mind of the time, the scientific principal of the ‘survival of the fittest’ was applied to social and ethnic groups.

Vienna and Berlin thought that the final battle between ‘Germandom’ and ‘Slavdom’ was imminent and gladly posed as the defenders of a German-dominated Central Europe threatened by ‘Eastern hordes’. The Habsburg Monarchy was interpreted as a bulwark against ‘pan-Slavist Russia’ and the ‘barbaric Balkans’. Political circles were dominated by a dangerous mixture of imperialist thinking and German nationalist chauvinism.

Others considered that ‘attack as the best form of defence’ was the only possible way of avoiding the threat of going under entirely. These parties understood war as a way of pursuing political ends with other means, and as a ‘bid for liberation’ that would pre-empt the danger of collapse and disintegration. The political faction intent on escalation took refuge in the time-hallowed method of overcoming an internal crisis: rallying the forces by pointing to a common enemy. As Chief of General Staff Conrad von Hötzendorf put it: ‘Only through an aggressive policy with positive goals can we succeed and save ourselves from downfall.’

This renewal of the Monarchy, however, was to take place under the aegis of authoritarian principles. The general enthusiasm for war and the interventions in the political system necessitated by the war were therefore to be used to root out democratic ideals. The image of the ‘Gordian knot’ that can only be undone with the slash of a sword was exploited for all it was worth by those who argued that the long-standing and intractable problems could only be solved through force.

All this clearly reveals a fear that the modernization and progress which had already begun to erode the old structures and threaten the traditional systems and hierarchies would result in radical social change. The elites who had traditionally held the reins of power were seriously disturbed by the growing chorus of voices calling for social reforms and for the right to self-determination for peoples, classes, groups and individual human beings.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Beller, Steven: Franz Joseph. Eine Biographie, Wien 1997

Csáky, Moritz: Das Gedächtnis der Städte. Kulturelle Verflechtungen – Wien und die urbanen Milieus in Zentraleuropa, Wien [u.a.] 2010

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena/Schippler, Bernd: Schwarzbuch der Habsburger. Die unrühmliche Geschichte eines Herrscherhauses (2. Auflage, ungekürzte Taschenbuchausgabe), Innsbruck [u.a.] 2010

Leidinger Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien [u.a.] 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013

Quotation:

‘Only through an aggressive policy...', Conrad von Hötzendorf, Franz, quoted from: Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005, 236 (Translation)