Rebuilding for war: barracks and hospitals in Vienna

-

The arcaded courtyard of the University of Vienna as a hospital garden, photo from Österreichische Illustrierte Rundschau of 6 November 1914

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

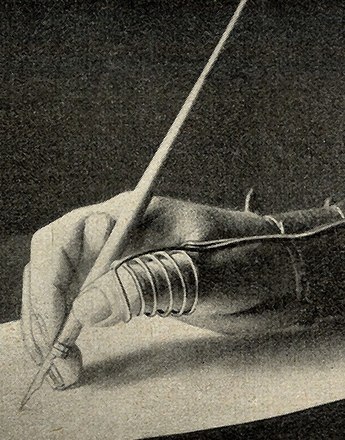

The wife of a reservist makes her small contribution to the Red Cross, photo from Wiener Bilder of 16 August 1914

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

Admissions hut of the No. 1 War Hospital in Ottakring, Vienna, , photo from: Österreichische Illustrierte Rundschau (issue of 31 December 1915)

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall

The outbreak of war put the dynamic urban development and construction in Vienna on hold. Building activity was dictated by the war, its unhappy progress and the inadequate preparation and organization. The constant flow of refugees and wounded soldiers made it necessary to transform Vienna into a city of barracks and hospitals.

The fortifications on the Bisamberg and along the Kahlenberg-Sophienalpe line (Vienna bridgehead) were reinforced on account of the war, and armaments production in the Arsenal was stepped up. New buildings of strategic significance included the Schiffsbautechnische Versuchsanstalt (Marine Engineering Research Institute) and the Exportakademie (and later Hochschule für Welthandel – University of World Trade). The Oesterreichisch-Ungarische Bank (and present-day National Bank) and Technical Museum were completed. In January 1915 the city council invited tenders for an ‘österreichische Völker- und Ruhmeshalle’ (Austrian Hall of Fame). Otherwise there were few commissions for public buildings. Various children’s homes were planned on the outskirts of Vienna, but only a few were built. The war created new priorities.

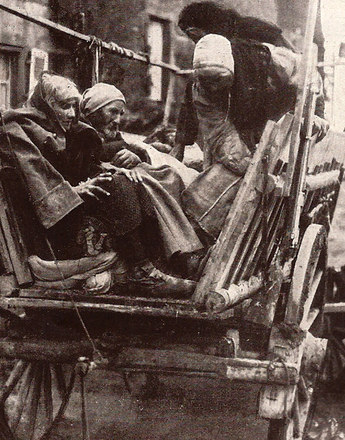

Vienna was the military logistics centre of the Habsburg Monarchy during the war, the administrative centre of all war efforts at the front and behind the lines. It was an important garrison town and became a collection point for both wounded soldiers and refugees from the war zones. Possibly the most important building focuses were the construction of barracks (in Simmering, Favoriten, Meidling and Grinzing) for the medical care of tens of thousands of wounded soldiers. By March 1916, seven war hospitals, ninety-one Red Cross stations, eleven emergency clinics, nineteen canteens and nine charity centres had been built. Added to this, diseases like tuberculosis, smallpox and typhus began to develop, with hunger, dirt and poor hygiene contributing to their rampant spread. A further building focus resulted from the dire supply situation. Vienna needed storage space to keep the materials necessary for war. Apart from the construction of the Municipal Cold Storage, nine warehouses in the Freudenau winter harbour were taken over by the city.

The war called for a process of adaptation. Hotels and boarding houses were rented to house the new departments and offices. Empty buildings (such as the Freihaus or the old circus in Zirkusgasse) as well as former dance halls and restaurants were requisitioned as soldiers’ quarters. Practically half of Vienna’s schools were transformed for military purposes right after the outbreak of war and served as quarters for soldiers and later for the war-wounded. The city’s hospitals were no longer sufficient to look after the wounded, and even Ringstrasse buildings like the university, parliament, Secession and Künstlerhaus were converted into hospitals. Vienna became a huge hospital. In 1915, for example, 260,000 casualties were treated in Vienna. Orphanages were emptied to look after wounded soldiers, and bourgeois families were paid to house the children. One of the major priorities, even after the war, was the erection of emergency accommodation for the mostly impoverished refugees and homeless persons. In 1919, the community began to convert the empty barracks and some school buildings into emergency housing. In the no longer used Kagran and Rossau barracks and in the Arsenal some 515 emergency apartments were created for the homeless, and buildings that had not been completed because of the war were purchased and adapted.

There was a further change in everyday life. As the city filled up with refugees, soldiers and casualties, there was a need for transport planning and organization because of the increasing chaos on the streets, the growing number of accidents and the crowded trams, which were being used to transport goods and wounded combatants. There were increasing calls for the ban on overloading to be observed. One curious by-product of this reorganization of the city was the ban on exposed hatpins in the trams.

Translation: Nick Somers

Békési, Sándor: Straßenbahnstadt wider Willen oder zur Verkehrsmobilität im Hinterland, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 452-461

Fischer, Karl: Garnison, militärische Einrichtungen, in: Csendes, Peter/Opll, Ferdinand (Hrsg.): Die Stadt Wien (Österreichisches Städtebuch 7), Wien 1999, 185-210

Hufschmied, Richard: Energie für die Stadt. Die Kohlenversorgung von Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 180-189

Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas: Die Pflicht zu sterben und das Recht zu leben. Der Erste Weltkrieg als bleibendes Trauma in der Geschichte Wiens, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 14-31

Quotes:

"Vienna was the military logistics centre …": Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas: Die Pflicht zu sterben und das Recht zu leben. Der Erste Weltkrieg als bleibendes Trauma in der Geschichte Wiens, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 16 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- The growing city: Vienna on the eve of the First World Wa

- The war takes over the city

- Rebuilding for war: barracks and hospitals in Vienna

- Vienna as a refugee camp

- Vienna as a centre of the war economy

- Goodbye to the world of yesterday

- Self-help: unofficial allotments and deforesting the Vienna Woods

- Overthrow of the old values: post-war Vienna