The metropolis as melting pot III: Budapest and Pressburg/Bratislava

Budapest was the second capital of the Dual Monarchy and grew rapidly to become a European metropolis. While Budapest took on a decidedly Magyar character, Pressburg/Bratislava remained a classical example of the multi-ethnicity of many central European cities.

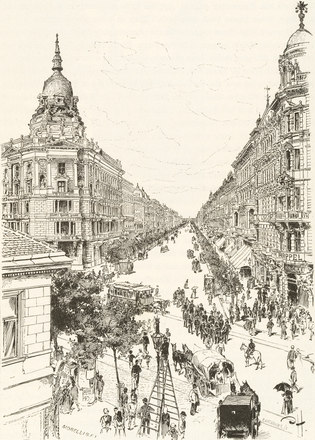

Following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Budapest, which was only created in 1873 through the merger of the former independent towns of Buda (known in German as "Ofen"), Pest and Obuda (German "Alt-Ofen"), acquired a new significance as the Hungarian metropolis.

Budapest rose rapidly from a provincial town to a dynamic cultural centre. The population of just under 500,000 in 1890 had risen to just under 1 million by 1910, making Budapest one of the most rapidly growing cities of Europe. This was due to the huge immigration from various parts of the ethnically heterogeneous country. The young capital was a melting pot for the non-Magyar citizens of the country. Immigrants of German, Slovak and South Slav origin merged to become nationally minded Hungarians. While in 1850 the Hungarian capital was still an ethnically mixed city – the dominant German-speaking middle-class was surrounded by Magyars, Slovaks, Serbs etc. – the rigid Magyarisation policies in the years up to 1900 changed it into a metropolis with a clearly Hungarian-Magyar character. This was reflected in the new self-awareness of the Hungarian nation in the millennium celebrations of 1896, recalling the Magyar occupation of the country one thousand years previously. The monumental buildings and memorials dedicated to the Hungarian national history that were constructed at the time are still a major feature of Budapest's urban landscape today.

The accelerated Magyarisation policies of the Hungarian government also had effects on other cities of the kingdom, which, like the country itself, were themselves often ethnically very mixed. An example is Pressburg, where the variety of names used for this city itself betrays the linguistic heterogeneity of the inhabitants. The old Pressburg, which, when large parts of Hungary were under Ottoman rule, was for a time even the capital of the Kingdom of Hungary, was referred to by the Hungarians as Pozsony and by the Slovaks as Prešporek (today's name, Bratislava, was only created in 1919).

Pressburg/Bratislava is a classical example of the intense cross-cultural interference that characterised many urban centres of central Europe. Large numbers of people could not be unequivocally classified as belonging to one language group, since the phenomenon of bilingualism or multilingualism was very common. For this reason, the statistics are often only a reflection of the current political climate in the nationalities question, since people changed their official membership of one or another language group depending on political circumstances.

In 1901, Pressburg had a population of around 66,000, 50.4% of whom gave German as their mother tongue, 30.5% Hungarian and 16.3% Slovakian. In 1910, i.e. only a few years later, strict Magyarisation policies had significantly shifted the linguistic distribution to the benefit of the Magyars: Germans still accounted for 41.9%, but were only marginally ahead of the Magyars with 40.5%, while Slovaks had fallen to 14.9%. The extent to which these figures can alter as a result of political changes is shown by a comparison with 1930, when Bratislava had become part of Czechoslovakia. Of the now 120,000 inhabitants, 51.3% identified themselves with the Slovak ethnic group, 20.1% with the German and only 16.2% with the Hungarian.

Translation: David Wright

Csáky, Moritz: Das Gedächtnis der Städte. Kulturelle Verflechtungen – Wien und die urbanen Milieus in Zentraleuropa, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Hanák, Péter: Die Geschichte Ungarns. Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart, Essen 1988

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Ungarns 1867–1983, Stuttgart 1984

Lukács, John: Budapest um 1900. Ungarn in Europa, Berlin 1990

Luther, Daniel: Bratislava a mýtos multikultúrnej tolerancie [Bratislava und der Mythos der multikulturellen Toleranz], in: Soukupová, Blanka u. a. (Hrsg): Mýtus – „realita“ – identita. Státní a národní metropole po první světové válce [Urbanní studie 3], Praha 2012, 107–119

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- The metropolis as melting pot I: Vienna – migration under the Emperor

- The metropolis as melting pot II: Prague

- The metropolis as melting pot III: Budapest and Pressburg/Bratislava

- School as a place of conflict: national agitation in the classroom

- The Moravian Compromise: light at the end of the tunnel?

- The Islam Law of 1912: an example of the integrative effect of the multi-ethnic empire

- The "right of the peoples to self-determination" – the patent solution to ethnic conflicts?