School as a place of conflict: national agitation in the classroom

In the old Habsburg Monarchy, school policies were an ideological landmine. The extent to which national emotions clouded the view is shown by examples where educational policy decisions led to nationalist escalation and shook the foundations of the Monarchy.

The Cilli school dispute that caused a furore in 1895 was the most serious of the national conflicts in the school sector, its shockwaves extending far beyond the original local setting.

The background was the struggle by the Styrian Slovenes to gain emancipation from the cultural hegemony of the German-speaking Styrians. The town of Cilli (in Slovene Celje) was a German language island in the otherwise Slovene-dominated Lower Styria. The Slovene representatives, wanting to improve their underprivileged situation in the face of German-speaking dominance in the educational sector, demanded the introduction of parallel classes in Slovenian at the local grammar school as a means of remedying the obvious shortage of higher Slovene schools in Styria. Although their cause was legitimate, a dispute arose on the question of the location, since the local German-speaking dignitaries saw themselves as the bastion of German traditions, while the Slovenes insisted that the school should be in Cilli ("Cilli or nothing") in order to underline their claim that they were the regional majority. In the charged atmosphere, the local dispute became a serious political conflict, since it was the first time that the German deputies from the Alpine countries refused to support the government's consensual policies. Within the German-speaking political scene, the Cilli school dispute became a symbol of the shift to an emphatically militant national position.

However, it was not only in the provinces of the Monarchy that educational policies were determined by chauvinistic agitation. In Vienna too, the multi-ethnic metropolis of the Monarchy, the school became the setting for nationalist power struggles, as shown by the example of the Viennese Czechs. As a result of a huge influx of immigrants, the Czechs became the largest of the non-German language groups in the city. Their demand for mother-tongue teaching was rejected in 1896/97 by a regulation of the Lower Austrian Diet that laid down that German was the exclusive language of teaching for all public schools in Lower Austria, of which Vienna was a part at that time.

The Czech community of Vienna contested this regulation before the Reichsgericht (whose functions correspond today with those of the Constitutional Court), which however in 1904 refused to recognise Czech as a customary language despite the large numbers who spoke it. This status formed the basis for the right to mother-tongue education, but according to the court it could only be attributed to long-standing autochthonous ethnic groups, while the presence of Czechs in Vienna, in the judges' opinion, was only the result of recent migration.

Here again, the reactions went far beyond the local setting. The Vienna Czech community was supported by the entire Czech political scene. The Czechs felt themselves disadvantaged in their national development and wanted to see an emphasis on the multi-ethnic character of the imperial capital of the Austrian multi-ethnic state, which had in their eyes long ceased to be a unitary state led by German speakers: "Vienna does not want to be concerned with the intellectual needs of the Czech population, it is not behaving like the first city of the Austrian state but rather like the capital of an eastern province of Germany," was the bitter reaction of a contemporary commentator.

The protests of the Czechs in the Imperial Diet were followed by demonstrations by the German national scene in support of "the preservation of the German character of the city", as encouraged by the Mayor Karl Lueger, and opposing any tendency to impose a multicultural character on the imperial capital.

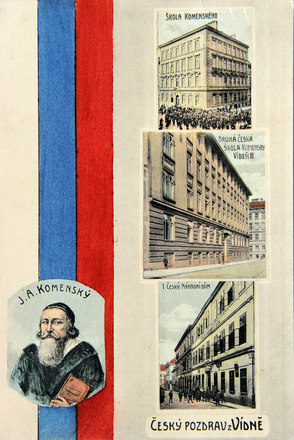

The intransigence of the Vienna school authorities led to the Czech-speaking compulsory schools of the Komenský School Association having to be operated as private schools without public rights. In order to take examinations in Czech, the pupils had no alternative but to travel to the Moravian border town of Lundenburg (in Czech Břeclav), the site of the nearest Czech-language state school. The Czech schools of Vienna were only granted public rights after 1918, in the First Republic.

Translation: David Wright

Brousek, Karl M.: Wien und seine Tschechen. Integration und Assimilation einer Minderheit im 20. Jahrhundert (Schriftenreihe des österreichischen Ost- und Südosteuropa-Instituts 7), Wien 1980

Csáky, Moritz: Das Gedächtnis der Städte. Kulturelle Verflechtungen – Wien und die urbanen Milieus in Zentraleuropa, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Scheu, Harald Christian: Die Stellung von Minderheiten und Volksgruppen in Wien zwischen 1918 und 1934, in: Soukupová, Blanka u. a. (Hrsg): Mýtus – „realita“ – identita. Státní a národní metropole po první světové válce [Urbanní studie 3], Praha 2012, 33–53

Quotation:

"Vienna does not want to be concerned ...": newspaper article from „Der Parlamentär“, 1892, zitiert nach Csáky, Moritz: Das Gedächtnis der Städte. Kulturelle Verflechtungen – Wien und die urbanen Milieus in Zentraleuropa, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010, 143 (translation)

-

Chapters

- The metropolis as melting pot I: Vienna – migration under the Emperor

- The metropolis as melting pot II: Prague

- The metropolis as melting pot III: Budapest and Pressburg/Bratislava

- School as a place of conflict: national agitation in the classroom

- The Moravian Compromise: light at the end of the tunnel?

- The Islam Law of 1912: an example of the integrative effect of the multi-ethnic empire

- The "right of the peoples to self-determination" – the patent solution to ethnic conflicts?