The Moravian Compromise: light at the end of the tunnel?

The Moravian Compromise was one of the few positive examples of an approach to a fair solution in the field of nationalities policies. Despite the deadlock in the language dispute between Czechs and Germans, a compromise acceptable to both sides and allowing a harmonious coexistence was found here.

Following the escalation that followed the Badeni Language Decree of 1897, the Koerber government cautiously began in 1900 to try to de-escalate the situation in Bohemia. Attempts to reach a compromise once again failed in the face of the irreconcilable attitudes of both German and Czech politicians.

In Moravia, however, success proved possible. In this Crown Land, the two language groups lived alongside each other in less strict geographical and social separation than in Bohemia, which was completely split by the German-Czech antagonism.

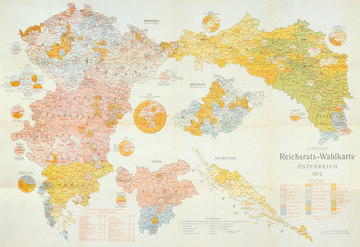

In 1905, a compromise was drawn up that represented a model solution to the power struggle between the national groups. Under the name Moravian Compromise, an agreement was reached on a new regional structure, above all with respect to the organisation of political representation in the Diet.

Thanks to a new electoral register broken down into national curias, a specific number of seats were reserved for each national group according to a fixed formula. It was only possible to vote for candidates within the curias, with the result that Czechs could only vote for Czechs and Germans only for Germans. The aim was to prevent one side out-voting the other, as occurred under the previously purely geographical arrangement, with electoral wards with frequently mixed populations. This national electoral register was based on the principle of personal autonomy, developed by the then Social Democrat member of the Diet and subsequent Chancellor in the First Austrian Republic, Karl Renner (1870 – 1950) as a way of solving the paralysing nationalities dispute.

A decentralised model was also introduced concerning the use of the languages of the country in dealings with the public authorities. Each local authority was at liberty to choose a business language, the only requirement being that the needs of the language minority should not be ignored. Czech, German and mixed districts were defined. When filling public sector vacancies, the prevailing language at the place of employment had to be respected and account taken of the local ratio between the language groups. The split into two parallel language spheres was also enforced in the school system. School districts were separated according to language and two separate sections for the two nationalities set up in the provincial school board.

The Moravian solution led to a perceptible reduction of nationalist extremism and was regarded as a successful model that was also applied to the Bukovina with its four languages. A similar compromise, between the Poles and Ruthenians, was also negotiated in 1914 for Galicia but was frustrated by the outbreak of war.

Even in Bohemia, where the heated situation had slowly calmed down again, a new approach was started. A Czech-German committee with equal representation of the two language groups was set up, and was close to a breakthrough in 1912. However, an at least temporary compromise failed once again in the face of nationalist extremists on both sides. The change in conditions following the outbreak of war in 1914 prevented a solution being found for the problem of national coexistence, which was one of the main reasons for the subsequent collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy. The problem continued for a long time to afflict the relationship between Czechs and Germans.

Translation: David Wright

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Böhmens. Von der slavischen Landnahme bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, München 1987

Kořalka, Jiří: Tschechen im Habsburgerreich und in Europa 1815 bis 1914. Sozialgeschichtliche Zusammenhänge der neuzeitlichen Nationsbildung und der Nationalitätenfrage in den böhmischen Ländern (Schriftenreihe des Österreichischen Ost- und Südosteuropa-Instituts 18), Wien 1991

Křen, Jan: Dvě století střední Evropy [Zwei Jahrhunderte Mitteleuropas], Praha 2005

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

-

Chapters

- The metropolis as melting pot I: Vienna – migration under the Emperor

- The metropolis as melting pot II: Prague

- The metropolis as melting pot III: Budapest and Pressburg/Bratislava

- School as a place of conflict: national agitation in the classroom

- The Moravian Compromise: light at the end of the tunnel?

- The Islam Law of 1912: an example of the integrative effect of the multi-ethnic empire

- The "right of the peoples to self-determination" – the patent solution to ethnic conflicts?