The Islam Law of 1912: an example of the integrative effect of the multi-ethnic empire

In 1912, Islam was recognised officially as a religious community with equal rights within the Austrian half of the Empire. In the Christian world of European countries, the Habsburg Monarchy played a pioneering role in this field, and the law's basic features continue to apply today.

Imperial Gazette No. 159/1912 was the result of a cautious approach to Islam and its extensive influence on Moslem society and law. State recognition of Islam as a religious community in Cisleithania was an attempt to integrate Muslims in the Habsburg Monarchy, including those outside Bosnia.

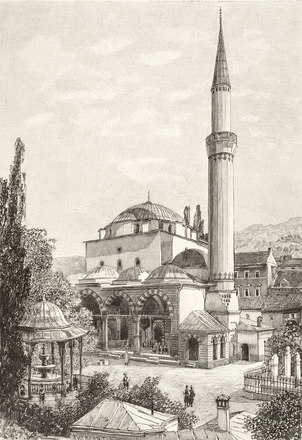

The occupation (1878) and annexation (1908) of Bosnia and Herzegovina brought a country with a Moslem population into the Habsburg Monarchy. Bosnia's integration into the Monarchy as a whole led to Muslims moving into other parts of the Empire, both in the civilian and the military sector.

The extent of migration, however, was relatively small. In the 1910 census, a total of 1,446 persons professed to being Moslems in Cisleithania. Most of these Moslems, 699, were based in Lower Austria, of which Vienna was a part at that time. However, the details are imprecise, since Moslems were often classified under other religious groups in the statistics.

The main obstacle to integration was the different organisational structure of the Moslem religious community, from the point of view of the Habsburg administration, since it was much less hierarchically organised than the Christian denominations. In addition, the rules of Islam had a much greater influence than other religions not only on the religious practices of the faithful but also on many other aspects of daily life, family and criminal law, and the organisation of the community.

For this reason, the existing laws on freedom of religion were regarded as insufficient. The newly created statutory conditions were therefore tailor-made to meet conditions amongst the Bosnian Moslems. The Islam Law of 1912 expressly referred to the Moslem members of the Hanafi rite. The Hanafis are the largest group within Sunni Islam, accounting for over 40% of Moslems, and was predominant in Turkey, the Middle East and, of relevance in this case, the European territories of the Ottoman Empire.

Despite the extensive accommodation of Islam, the new law also involve restrictions. Thus for instance family law imposed a prohibition on polygamy and required the conclusion of a civil marriage ceremony. Since Moslems were not permitted to have their own civil registers, like the Christian and Jewish communities could, they were reliant on the state registry offices.

Full use was never made of the potential of the Islam Law, since the Habsburg Monarchy had only a few more years to live. Thus it was not possible to develop community structures for the Moslems in Cisleithania similar to those for the Christian and Jewish religions. For this reason, they never enjoyed the privileges to which officially recognised religious communities were entitled according to the law.

The construction of a mosque in Vienna was also prevented by the outbreak of war in 1914, although Emperor Franz Joseph had promised a donation of an impressive 250,000 guilders and the City of Vienna had made available a site at Laaer Berg.

Following the collapse of the monarchy, hardly any Moslems were still living in Austria or Vienna. The question only arose again in the face of guest worker immigrants from the 1960s on. The Islam Law, which continued to remain in effect in the Republic, was only extended in 1988 when the restriction to the Hanafi Sunni school was set aside and the provisions extended to all versions of Islam.

Translation: David Wright

Heine, Susanne / Lohlker, Rüdiger / Potz, Richard: Muslime in Österreich. Geschichte – Lebenswelt – Religion. Grundlagen für den Dialog, Innsbruck 2012

Karčić, Fikret: The Bosniaks and the Challenges of Modernity, Sarajevo 1999

Stourzh, Gerald: Die Gleichberechtigung der Nationalitäten in der Verfassung und Verwaltung Österreichs 1848 bis 1918, Wien 1985

-

Chapters

- The metropolis as melting pot I: Vienna – migration under the Emperor

- The metropolis as melting pot II: Prague

- The metropolis as melting pot III: Budapest and Pressburg/Bratislava

- School as a place of conflict: national agitation in the classroom

- The Moravian Compromise: light at the end of the tunnel?

- The Islam Law of 1912: an example of the integrative effect of the multi-ethnic empire

- The "right of the peoples to self-determination" – the patent solution to ethnic conflicts?