-

Shell hole in Ottokar Hanzel's emplacement, photograph, undated

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

Soldiers wearing gas masks loading shells, photograph, undated

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

On 23 May 1915, despite its alliance with Austria-Hungary and the German Empire, Italy entered the war on the side of the Entente. This act, sometimes referred to as ‘l’intervento’, aroused a wave of outrage and acrimony in the Monarchy. Later the same day a manifesto issued by Emperor Franz Joseph was published, capturing the general mood: ‘The King of Italy has declared war on me. A breach of fidelity the like of which is unknown in history has been perpetrated by the Kingdom of Italy on both its allies.’

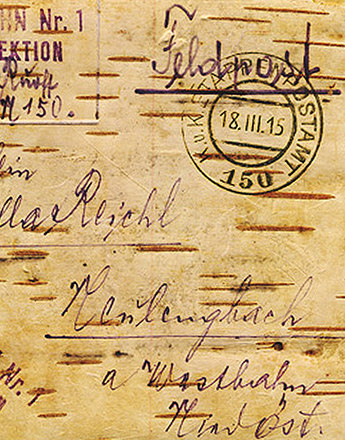

These sentiments are closely echoed by Ottokar Hanzel when describing Italy’s entry into the war in a letter to his wife dated 24 May 1915: ‘How much longer before the thunder of cannon echoes off the faces of the mountains. Italy has perpetrated an unparalleled breach of fidelity; may it be punished for this.’

For Ottokar Hanzel, who had been drafted into the reserve companies ‘Franzensfeste’ and ‘Riva’ until May 1915, the war became a direct threat that aroused concern and anxiety for his own wellbeing and that of his comrades in arms. His awareness that there was a very real possibility of his being wounded or killed caused Ottokar Hanzel to draw up his will in May 1915. The degree to which these daily threats occupied him can be seen from the following lines written to Mathilde Hanzel on 6 June 1915: ‘E. and I have agreed that if anything should happen to one of us, his wife will be notified by the other. Here is the address of E.’s wife [...]. Keep it somewhere safe.’

This is one of the rare passages where Ottokar Hanzel acknowledges directly to his wife that something might happen to him. It stands in direct contrast to most of his descriptions of everyday life at the front, which largely down-played the situation. Thus for example the following comment, from a letter dated 12 November 1915: ‘The firing from the Italians wasn’t bad and what is more was ineffective.’

His letters to Mathilde Hanzel seldom mentioned violence, battles or death. As in other correspondence from the front, particularly those written by officers, the constant danger and destruction were omitted from Ottokar Hanzel’s letters. When he did write about what he was doing at the front he tended to describe visiting other officers or superiors, or harmless leisure occupations such as swimming or reading; his military duties and activities remain vague and his letters give little insight into his actual routine or duties.

The evocation of ‘normality’ that can be seen in Ottokar Hanzel’s letters was intended to spare the feelings of the loved ones they were addressed to. In addition to this form of self-censorship the official censorship regulations also had a limiting effect on what he chose to relate.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Hämmerle, Christa: „… wirf Ihnen alles hin und schau, dass Du fortkommst.“ Die Feldpost eines Paares in der Geschlechter(un)ordnung des Ersten Weltkriegs, in: Historische Anthropologie (1998), 6/3, 431-458

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: „Wenn wir nur glücklich wieder beisammen wären …“ Der Krieg, der Frieden und die Liebe am Beispiel der Feldpostkorrespondenz von Mathilde und Ottokar Hanzel (1917/18), Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Wien 2010

Sturm, Margit: Lebenszeichen und Liebesbeweise aus dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Zur Bedeutung von Feldpost und Briefschreiben am Beispiel der Korrespondenz eines jungen Paares. Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Universität Wien 1992

Quotes:

„The King of Italy has declared war on me ... “: Manifesto by Kaiser Franz Joseph from 23 May 1915, in: Extraausgabe der „Wiener Zeitung“, 24 May 1915, quoted from: Afflerbach, Holger: Der Dreibund. Europäische Großmacht- und Allianzpolitik vor dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2002, 870 (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

„How much longer before the thunder ...“: Ottokar Hanzel to Mathilde Hanzel, 24.05.1915, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

„E. and I have agreed that if anything should happen ...“: Ottokar Hanzel to Mathilde Hanzel, 06.06.1915, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

„The firing from the Italians ...“: Ottokar Hanzel to Mathilde Hanzel, 12.11.1915, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

-

Chapters

- How does a collection of letters come to be stored in an archive?

- The protagonists: Mathilde Hübner and Ottokar Hanzel

- Love, marriage, career

- The separation begins

- ‘War fever’ versus the longing for peace

- Italy’s ‘betrayal’ in 1915

- ‘… surely this war must end some time?!’

- ‘… and tomorrow we will start cheerily canvassing for peace.’

- Black marketeering, profiteering and self-subsistence

- A love affair in wartime