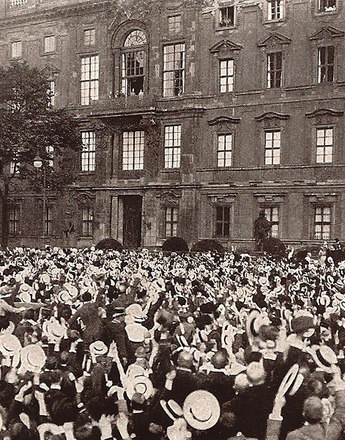

From the perspective of the present, the images of demonstrations of public ‘enthusiasm’ from August 1914 are puzzling and rather difficult to account for. After the wars and genocide of the twentieth century it is almost impossible to understand how the outbreak of conflict between nations could be greeted with such fervour. However, there is a plethora of photographic evidence showing huge crowds of people in Vienna, Berlin or Paris celebrating with ‘exultation’ at the news.

According the historians Matthias Rettenwander and Oswald Überegger, many artists and intellectuals attempted to explain their personal experiences during those days in early August by resorting to the notion of a classless ‘community of the people’. As the two historians have demonstrated, the perspective of the so-called Augusterlebnis (‘August experience’) until very recently was adopted more or less uncritically by scholars researching this period. However, research carried out over the past few years into regional and everyday history, including personal accounts of the period, have led to doubts emerging about this postulated general enthusiasm for the war. More recent studies have shown that it was not a single mood shared equally by everyone; from the very beginning there were large numbers of critical and anxious voices.

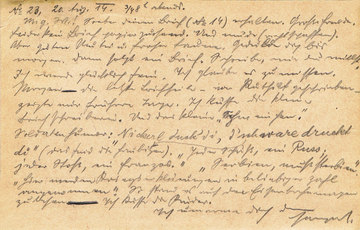

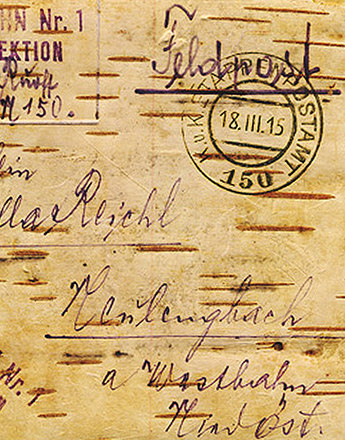

The mood of the letters written by the Hanzels in the first months of the war also veers between euphoria and censure. Ottokar Hanzel writes to his wife on 3 August 1914: ‘The movement of people that is now taking place and in which I am participating is overwhelming and without parallel in history. Only a modern state that is technically equipped [for it] can carry it out successfully. Until now everything has worked out well. Many are full of enthusiasm, almost all of us firmly resolved to do our part in this war that has seized all of Europe.’

In his letters from this time the ‘strength’ and ‘power’ of Austria’s ally Germany are invoked as is the will to fight and courage of the Austro-Hungarian forces. Ottokar Hanzel notes in August 1914: ‘We are all pleased at Germany’s powerful bearing, standing alone in the history of the world. We trust in the united strength of Austria and Germany, and will not be made to fear.’

Mathilde Hanzel saw the outbreak of war in a more critical light. On 12 August 1914 she writes: ‘I deeply lament every drop of blood that has been and will be spilled in this war. Yes, the fatherland, honour, justice; I recognize all that and do my duty; but that in the 20th century so-called civilized people can find no other expedient than war? What a debacle for humanity. Fighting, vanquishing, dying, survivors doomed. We are not yet possessed of true civilization!’

Mathilde Hanzel retained this critical attitude throughout the war. And in her husband’s letters the initially positive view of the war gradually faded. Like the majority of frontline soldiers and most of the population of the Monarchy he was convinced that it would be of short duration and over by Christmas at the latest, with Austria-Hungary and Germany emerging as victors. But when by December 1914 it became obvious that there was no end in sight, the first critical tones start to appear in Ottokar Hanzel’s letters. Thus on 4 December 1914 he writes: ‘Modern warfare is dreadful. On every combatant it places enormous and constant privation, strain, and sadly only too often unutterable suffering.’

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Überegger, Oswald/Rettenwander, Matthias: Leben im Krieg. Die Tiroler Heimatfront im Ersten Weltkrieg, Bozen 2004

Quotes:

„[…] many artists and intellectuals attempted to explain ... “: Überegger, Oswald/Rettenwander, Matthias, Leben im Krieg. Die Tiroler Heimatfront im Ersten Weltkrieg, Bozen 2004, 7

„The movement of people...“: Ottokar Hanzel to Mathilde Hanzel, 03.08.1914, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

„the strenght and power of Austria’s ally“: Ottokar Hanzel to Mathilde Hanzel, 16.08.1914, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

„We are all pleased at Germany’s ...“: Ottokar Hanzel to Mathilde Hanzel, 03.08.1914, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

„I deeply lament every drop of blood ...“: Mathilde Hanzel to Ottokar Hanzel, 12.08.1914, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

„Modern warfare is dreadful ...“: Ottokar Hanzel to Mathilde Hanzel, 04.12.1914, Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Nachlass 1, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien (Translation: Sophie Kidd)

-

Chapters

- How does a collection of letters come to be stored in an archive?

- The protagonists: Mathilde Hübner and Ottokar Hanzel

- Love, marriage, career

- The separation begins

- ‘War fever’ versus the longing for peace

- Italy’s ‘betrayal’ in 1915

- ‘… surely this war must end some time?!’

- ‘… and tomorrow we will start cheerily canvassing for peace.’

- Black marketeering, profiteering and self-subsistence

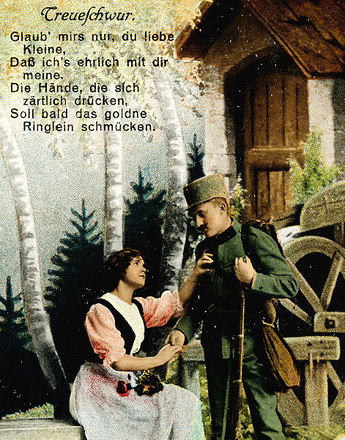

- A love affair in wartime