-

Cowpox vaccination certificate of Elisabeth Gollhammer, 1916

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

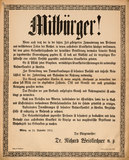

Information poster concerning the risks of contagious diseases, 1914

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall

Although the danger of epidemics was known, the Austro-Hungarian army was not well prepared at the start of the war to combat classic diseases like typhoid fever, cholera, dysentery, typhoid, smallpox or malaria.

To combat the spread of diseases within the army and civilian population, army doctors were required to report every case to their commanders and the responsible political authorities. Quarantine and observation wards were set up behind the lines to prevent the diseases from spreading further to the rear. Steam disinfection, drinking water treatment and hot air chambers, to mention but a few examples, were used to combat disease. Washing machines were purchased, bathing and cleaning stations set up and hygiene in the trenches and barracks monitored. Even postcards and packages had to be disinfected before leaving the hospitals.

In spite of all these measures, it was difficult to prevent and combat disease. The civilian population was insufficiently informed of the health of the troops. The cooperation between military and civilian authorities was also often problematic. Added to this was the fact that at the start of the war the Austro-Hungarian army had no isolation hospitals, so that soldiers suffering from an infectious disease had to be treated in makeshift and inadequately equipped isolation units. There was a shortage of serum preparations, microscopes, disinfectants and trained personnel.

In 1915 a few isolation hospitals were set up. The medical officers in charge were not familiar with the diagnosis or treatment of epidemic diseases, however, with the result that they were often misdiagnosed and incorrectly treated. Lieutenant Karl Fanta describes how the medical officers were overwhelmed: "Patients suffering from dysentery and typhoid fever lay together, and the doctors didn’t know what to do with them."

Vaccinations to prevent infectious diseases were gradually introduced. Troops did not receive vaccinations against dysentery, a serious intestinal disease that was widespread particularly in southern Hungary, Serbia, Bosnia, Galicia and Russia, until the second year of the war. By then 120,000 soldiers had contracted it and 5,000 had died of it. The Ministry of War was also hesitant about cholera vaccinations, arguing that the issuance of vaccine would weaken the troops. In the first three years of the war 16,266 soldiers died of cholera, mainly in Galicia, Russian Poland but also in Bosnia & Herzegovina. After the vaccine was issued by the Ministry, the death rate dropped significantly.

Typhoid fever vaccinations were also initially forbidden by the chief of general staff as they could have severe side effects making it necessary for the soldiers to be put under medical observation. At the start of the second year of the war, however, vaccination was allowed but it was very unpopular with the troops. As for smallpox, which occurred mainly on the eastern and north-eastern fronts, targeted vaccination was relatively successful. Typhus, transmitted by clothes lice and widespread above all in the Serbian army and among Austrian prisoners of war, was also finally curbed through systematic delousing.

Translation: Nick Somers

Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Teil 2, Wien 2002

Dietrich, Elisabeth: Der andere Tod. Seuchen, Volkskrankheiten und Gesundheitswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2011, 255-275

Quotes:

"Patients suffering from dysentery …": Aufzeichnungen Leutnant Karl Fanta, 122. Besitz von Dr. Karl Fanta, quoted from: Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Teil 2, Wien 2002, 541 (Translation)