The development of new weaponry produced novel and medically challenging injuries and diseases.

War surgeons studied weapon technology and the effects of projectiles on the human body so as to ensure a suitable treatment. Both the Central Powers and the Entente used missiles forbidden under international law. The Fourth Hague Convention of 1907 prohibited the use of "arms, projectiles, or material calculated to cause unnecessary suffering". This included in particular dum-dum, semi-jacketed and hollow-point bullets. These bullets disintegrated into fragments within the body or exploded, doubling the diameter of the bullet. A single hit caused severe injury to the tissue, extreme loss of blood and a large exit wound. Because of the fragmentation of the projectile, treatment was very difficult. Soldiers hit by a dum-dum bullet suffered particularly badly.

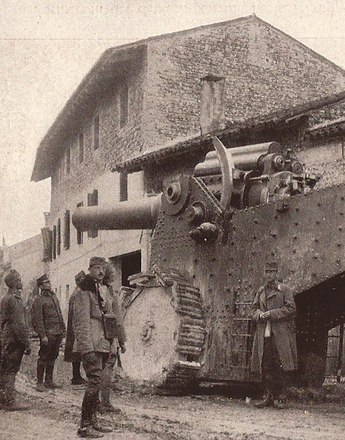

Three quarters of the wounds were caused by artillery shrapnel. They severed and destroyed whole parts of the body and because of the fragments distributed within the body entailed huge losses of blood. Grenade explosions caused dizziness, hearing impairment, paralysis and bleeding from the nose and mouth. Hand grenades also produced terrible injuries, loss of limbs and burns. Added to this were the serious injuries from aerial bombs, mortars and landmines. Poison gases like chlorine, phosgene or mustard gas caused mass devastation. Those who survived a gas attack often had lung inflammations and painful burns.

The conditions for treating the wounded at the front were often difficult. Operations and even amputations on occasion were performed at first-aid stations that were under fire. The medical orderlies had insufficient training. There was a shortage of blood, oxygen and respirators. The bandaging material and morphine were also inadequate to treat the injured soldiers. Iodine was used to disinfect wounds, and there were no antibiotics. Blood poisoning, tetanus and gangrene could have fatal consequences, although the introduction of vaccinations after the first months of the war significantly reduced deaths from tetanus.

The many injuries to the mouth and face, which disfigured soldiers to the point of unrecognizability, were particularly horrifying. Many lost half of their face, which had to be replaced by a prosthesis. In spite of progress in plastic surgery, many soldiers remained disfigured for life. As Karl Kraus wrote in Die Fackel in November 1916: "The face of this world will be a prosthesis." Kraus’s quotation highlights the general dismay at the countless men with facial injuries, which became a symbol of the atrocities of the Great War of 1914 to 1918.

Translation: Nick Somers

Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Teil 2, Wien 2002

Kraus, Karl: Die Fackel, Heft 437-442, 31.10.1916, 120. Unter: http://corpus1.aac.ac.at/fackel/ (23.06.2014)

Quotes:

"arms, projectiles, or material calculated …“: IV. Haager Abkommen, quoted from: Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Teil 2, Wien 2002, 475 (Translation)

"The face of this world …": Kraus, Karl: Die Fackel, Heft 437-442, 31.10.1916, 120. Unter: http://corpus1.aac.ac.at/fackel/ (23.06.2014), (Translation)