-

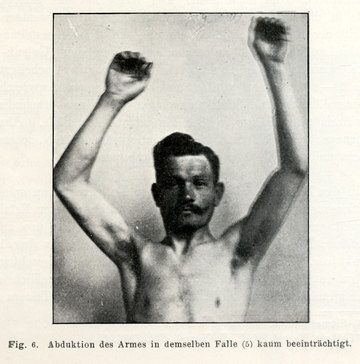

Detailed photo of a mentally ill soldier concerning the neurological effects of bullet wounds (2)

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

-

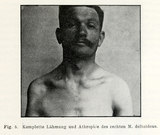

Detailed photo of a mentally ill soldier concerning the neurological effects of bullet wounds (3)

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

-

Detailed photo of a mentally ill soldier concerning the neurological effects of bullet wounds (4)

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

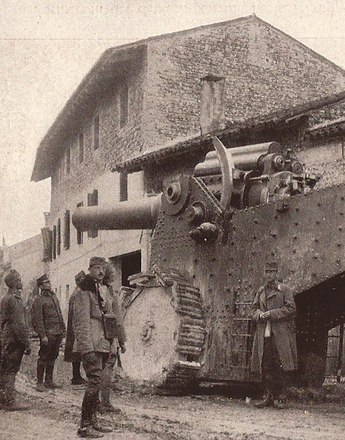

The First World War produced an army of emotionally damaged soldiers who could no longer bear the inconceivable destructive force of modern mechanical warfare. The diagnosis and treatment of mental diseases confronted military psychiatrists with new challenges.

Psychiatrists and neurologists were in no way agreed on the causes of mental disorders, but they were generally of the opinion that the symptoms were not organic or somatic but psychogenetic. The frequently observed locomotor disorders, twitching, trembling or paralysis appeared to indicate a form of male hysteria. Although it had been observed in men a long time before the First World War, it was generally characterised as a typically female disorder. For that reason its occurrence within the Austro-Hungarian army should be relativised.

According to the racial psychiatric interpretation, hysteria was commonplace above all in Slav and Romanian peoples and among Jews, while Germans were only marginally affected. Moreover, they argued, many hysterics faked their symptoms. The Viennese psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg suggested in an essay in the Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift in 1916/17 that the symptoms shown by hysterics served only to "gain advantage or avoid disadvantage". The distinction between "not wanting to be able" and "not being able to want", he said, was particularly difficult.

The trembling war hysteric was seen as the opposite of the heroic masculine soldier who fought wholeheartedly for victory. The symptoms had been considered hitherto to be typically feminine and for that reason diagnosis as a hysteric also asked questions about the soldier’s masculinity. Both patients and medical officers rejected the dishonourable term "hysteria" for military personnel. Instead, doctors preferred the term "neurasthenia", which was used as a synonym for nervousness or hysteria. It was a man’s disease and included different symptoms: nervous exhaustion, agitation, irritability and depression.

In the first two years of the war neurasthenia was a very frequent psychiatric diagnosis. After 1916 it progressed to being a disease specific to officers, an elite and privileged condition. From autumn 1916, psychogenic disorders of the 'simple soldier' were referred to extensively by the dishonourable term "hysteria".

Whereas the hysteric was a persona non grata, the neurasthenic, as neurologist Willy Hellpach put it, was "really the best among those with nervous injury" deserving a different type of treatment:

"The entire medical tone, which is tailored to hysteria, does not fit with neurasthenia. The hysteric requires a hard and implacable hand and even the use of force, because the sick hysteric’s will needs to be broken with a mighty blow. The neurasthenic, by contrast, requires sympathy, commiseration, consolation, a warm heart. [...] In the details of the therapy he needs everything that is poison to the hysteric and prolongs the hysteria. If you treat the neurasthenic like the hysteric, you run the risk of damaging him […] and possibly turning him into a hysteric."

The classification of the pathological symptoms, the diagnosis and the type of treatment therefore depended on the doctors and their individual ideologies. The origin and status of neuropathic patients played an important role in the medical diagnosis as a neurasthenic or hysteric.

Translation: Nick Somers

Hofer, Georg: „Nervöse Zitterer. Psychiatrie und Krieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 15-134

Schwarz, Peter: „Die Opfer sagen, es war die Hölle.“ Vom Tremolieren, Faradisieren, Hungern und Sterben. Krieg und Psychiatrie in Wien, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 326-335

Quotes:

"gain advantage …": Wagner-Jauregg, Julius: Erfahrungen über Kriegsneurosen III., in: Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift (1917), 67, 189, quoted from: Schwarz, Peter: „Die Opfer sagen, es war die Hölle.“ Vom Tremolieren, Faradisieren, Hungern und Sterben. Krieg und Psychiatrie in Wien, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 328 (Translation)

"really the best among those ...": Hellpach, Willy: Therapeutische Differenzierung der Kriegsnervenkranken, in: Medizinische Klinik (1917), 13, 1261, quoted from: Hofer, Georg: „Nervöse Zitterer. Psychiatrie und Krieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 45 (Translation)

"The entire medical tone …": Hellpach, Willy: Therapeutische Differenzierung der Kriegsnervenkranken, in: Medizinische Klinik (1917), 13, 1261, quoted from: Hofer, Georg: „Nervöse Zitterer. Psychiatrie und Krieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 45 (Translation)