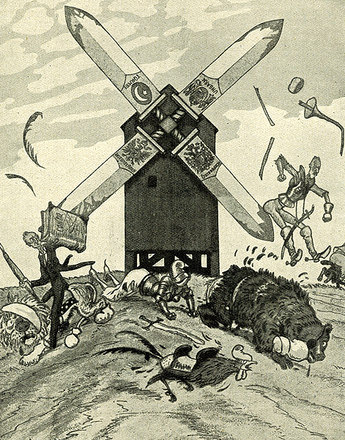

While the war was still raging, a new type of war-related condition was to be seen on the streets of European cities, with its sufferers twitching and trembling as illustration of the inconceivable destructive force of modern mechanical warfare. The condition came to be known as "shell shock".

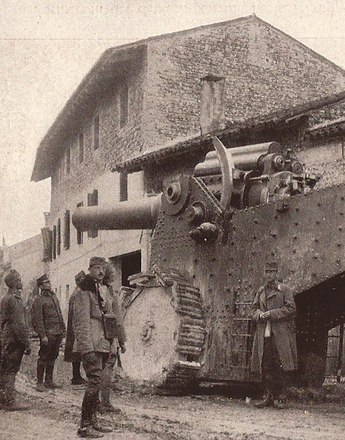

Mental diseases among soldiers reached a hitherto unseen dimension in the First World War. Mechanical warfare produced new subjective experiences: endless days in the trenches, the constant thunder of artillery fire and the sight of severely wounded and mutilated comrades put an immense mental strain on the soldiers and caused huge emotional trauma. The number of soldiers treated for nervous diseases by 1918 in Vienna alone is estimated at over 120,000.

Industrialised warfare made "strong nerves" one of the most important characteristics demanded of the troops. Not only physical but also mental strength was needed to put up with the extreme situation. "In a word: the passive strength of the nerves has extensively replaced the active strength of the muscles", is how Erwin v. Mattanovich, commander in chief of the Graz military command, put it. Many psychiatrists believed that the war contributed to training and hardening the nerves and thus to the strengthening of "soft" and "degenerate" societies. The mental diseases that occurred in their thousands after the first months of the war appear, however, to have rendered the idea of war as a way of steeling the nerves obsolete.

"Soon after the first enthusiasm for the war had dissipated, we saw an increasing number of people with trembling heads, arms and legs, pulling all kinds of faces, stuttering and unable to walk", is how the German psychiatrist Ernst Lüdemann described it.

The emotionally damaged soldiers had a variety of symptoms: twitching, trembling, paralysis, locomotor disorders, mutism or aphonia, stuttering, hearing or sight impairment, contorted limbs, vomiting, bed-wetting, depression, anxiety or twilight states. Depending on the symptoms, the disorders were described as "war neurosis", "war hysteria", "war psychosis", "war neurasthenia" or "mental shock". Today they would be called post-traumatic stress syndrome. The term "war neurosis" was an umbrella term for non-somatic disorders of the psyche or nervous system.

Diagnosis of the disease is based on the assumption that the observed symptoms are connected with specific traumatic experiences. This applies as much to soldiers in present-day wars as to the troops in the First World War. Traumata are not a universal, ahistorical category, however, and present-day pathologies cannot be applied retrospectively to qualify the mental disorders seen during and after the First World War. Diseases like "neurosis" or "hysteria" are not merely a description of "reality" but culturally manufactured phenomena whose historical context must also be taken into account.

Translation: Nick Somers

Hofer, Georg: „Nervöse Zitterer. Psychiatrie und Krieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 15-134

Hofer, Hans-Georg: Effizienzsteigerung und Affektdisziplin. Zum Verhältnis von Kriegspsychiatrie, Medizin und Moderne, in: Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 219-242

Hofer, Hans-Georg: Was waren „Kriegsneurosen“? Zur Kulturgeschichte psychischer Erkrankungen im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Kuprian, Hermann J. W./Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung. La Grande Guerra nell’arco alpino. Esperienze e memoria, Innsbruck 2006, 309-321

Schwarz, Peter: „Die Opfer sagen, es war die Hölle.“ Vom Tremolieren, Faradisieren, Hungern und Sterben: Krieg und Psychiatrie in Wien, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 326-335

Quotes:

"In a word: the passive strength …": Feldmarschall Leutnant Erwin v. Mattanovich: Mut und Todesverachtung, Graz 1915, 9, quoted from: Hofer, Georg: „Nervöse Zitterer. Psychiatrie und Krieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 59 (Translation)

"Soon after the first …": Ernst Lüdemann: Die Nerven. Ihr Wesen, ihre Gesunderhaltung, München 1928, 186, quoted from: Hofer, Georg: „Nervöse Zitterer. Psychiatrie und Krieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 51 (Translation)