Invalid pensions, allowances for wounded veterans, state support and maintenance contributions

The Habsburg Monarchy was in no way prepared for the provision of the many war invalids. A practically impenetrable jungle of improvised measures lasting until the end of the war proved hardly adequate to regulate this agenda.

The dimension of the First World War, the use of new weaponry and technology, national service and not least medical progress were the reasons that this war, like no other before it, left behind a host of wounded, gravely ill young men, who were marked for their whole lives.

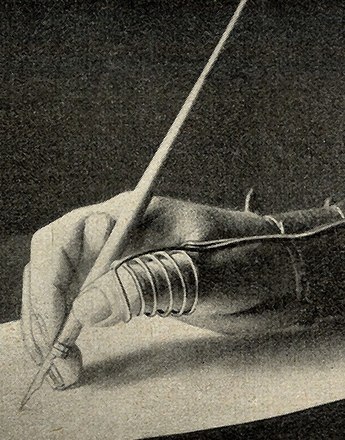

The Habsburg Monarchy was badly prepared for this situation. The old military provision law of 1875, although first put into force after general national service was introduced in 1868, was actually tailor-made for a professional army and entirely unsuitable to cope with the consequences of a war waged under conditions of national service. A soldier serving less than ten years could claim a invalidity pension only if it was clear he would remain permanently and completely incapable of working. There was no provision at all for the great mass of war invalids who, although showing limited employment capability, were still capable – with support – of leading a half-way normal life. They received no more than a small Verwundungszulage (injury allowance).

Instead of introducing an adequate legal regulation of this situation, the Monarchy relied during the war on constantly new, extremely complicated improvisations that could hardly be understood even by the administration: from 1915 on, the Unterhaltsbeiträge (maintenance contributions) issued to relatives of draftees were continued in case of the draftees’ invalidity. But if the invalid had no family, he was reliant upon staatliche Unterstützung (state support); this was raised in early 1918 and renamed Zuwendung (financial contribution).

However, all these support payments – which were devalued during the war on account of the rising cost of living – could be claimed by soldiers only if they could prove their need. An overall, unified provision for war invalids never existed until the end of the war. This was mainly because no consensus could be reached between the Austrian and the Hungarian halves of the empire: Hungary, which contributed less in per cent to the joint budget than it received for its war invalids, blocked all change. Austria thus profited from regulating the provision of its own invalids single-handedly – therefore also as a patchwork system.

It remained reserved for the First Republic to set up a comprehensive provision for war invalids: the Invalids Compensation Act of April 1919 was an example to the world and guaranteed provision of Austrian war invalids for the first time independently of rank and service duration. These men now received a pension that was assessed exclusively according to the harm done and its influence on employment capability.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Pawlowsky, Verena/Wendelin, Harald: Die normative Konstruktion des Opfers. Die Versorgung der Invaliden des Ersten Weltkrieges, in: Cole, Laurence/Hämmerle, Christa/ Scheutz, Martin (Hrsg.): Glanz – Gewalt – Gehorsam. Militär und Gesellschaft in der Habsburgermonarchie (1800 bis 1918) (=Frieden und Krieg. Beiträge zur Historischen Friedensforschung 18), Essen 2011, 359-383

Pawlowsky, Verena/Wendelin, Harald: Government Care of War Widows and Disabled Veterans after World War I, in: Contemporary Austrian Studies, XIX: From Empire to Republic: Post-World War I Austria (2010), hg. v. Bischof, Günter/Plasser, Fritz/Berger, Peter, 171-191

-

Chapters

- Invalid pensions, allowances for wounded veterans, state support and maintenance contributions

- The failure of private welfare

- The hospitals

- From recovery to reintegration: the training of invalids

- Work for war invalids

- Heroes or victims? War invalids and their impact on general awareness

- Forms of war injury

- Discontent and misery: war invalids get organised