From recovery to reintegration: the training of invalids

-

Announcement by the Vienna City Hall concerning the medical treatment and practical training of war invalids, poster, 1915

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

An invalid musician; from Das interessante Blatt, issue No. 3 of 20 January 1916, p. 12

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall

For the first time during the First World War it became clear that specific measures had to be taken to reintegrate draftee war invalids into employment again. This gave rise to the idea of training invalids.

It did not take very long before the war-waging nations – thus also the Habsburg Monarchy – had to face up to the problem that war invalids needed more than just medical care: if the countries wished to avoid providing for them permanently, it was imperative to enable them to return to a civilian occupation. This was also necessary in view of the competition on the job market, and it became virulent particularly at the end of the war, when uninjured soldiers were returning home from the front. But many of the war invalids could no longer pursue their original occupations because of their disabilities and thus had to be re-trained. The slogan was born of training for invalids.

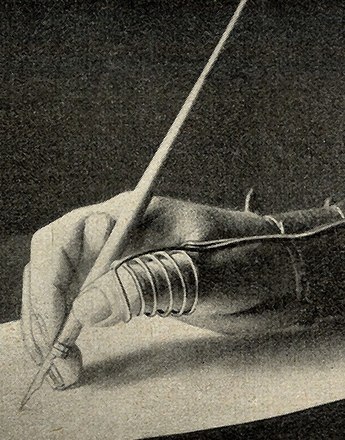

This training started while still in the hospitals, with work therapy. Its purpose was to re-mobilise stiff and lamed limbs, or train the application and use of prostheses. Subsequently, war invalids could then attend various courses. Nearly all commercial and agricultural educational institutions offered training courses for invalids, also many private associations. There was a wide range of options, from literacy and type-writing to regular occupational training. However, not all war invalids exploited these opportunities voluntarily, they often had to be persuaded. Training of invalids was at the heart of war invalid welfare, since it was an ideal example of demonstrating the possibility of re-integrating war invalids into civil life, their return to normality.

The widely publicised measures suggested that every man – if willing and correspondingly trained – could become a fully employable citizen again. There were several impressive successes – musicians with false limbs and blind basket-makers did indeed exist – but in many cases the authorities hoped for more from these courses than they actually achieved. Most by far of the draftees came from agriculture and went back to it, invalids or not. On the other hand, re-training was not suitable for tubercular war invalids. Thus the number of trainees registered by facilities for training invalids remained relatively small, at only 15 %. After the war – when war invalids could no longer be kept in the trainings facilities – training for invalids very quickly disappeared again from the agenda. Despite this, war invalids could still claim free training until 1927.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Pawlowsky, Verena/Wendelin, Harald: Die Verwaltung des Leides. Kriegsbeschädigtenversorgung in Niederösterreich, in: Melichar, Peter/Langthaler, Ernst/Eminger, Stefan (Hrsg.): Niederösterreich im 20. Jahrhundert, Bd. 2: Wirtschaft, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2008, 507-536

-

Chapters

- Invalid pensions, allowances for wounded veterans, state support and maintenance contributions

- The failure of private welfare

- The hospitals

- From recovery to reintegration: the training of invalids

- Work for war invalids

- Heroes or victims? War invalids and their impact on general awareness

- Forms of war injury

- Discontent and misery: war invalids get organised