-

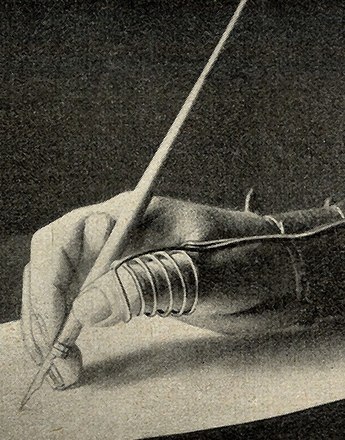

War invalids seeking employment in the Österreichischen Arbeitsnachweis für Kriegsinvalide of 15 December 1915

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

Advertisement for the Imperial-Royal Employment Placement Agency for War Invalids, poster, 1917

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall

Helping war invalids to become employable again was not enough. Hence action was taken already during the war in order to re-integrate them in practice into the work process.

War invalids could not attain the same performance level in their work as healthy employees. Therefore, the invalids compensation law enforced after the war specified the measure of disability – and thus the level of the pension – according to the reduction in employability. Individual job centres were set up for war invalids already during the war, designed to meet the needs of this group. Here it was relatively easy to accommodate war invalids, since employers were forced to employ personnel with physical disabilities on account of the war-related lack of manpower. For example, the military was interested in deploying war invalids in the armaments industry. However, the state committees for the welfare of returning soldiers, which formed the pool of authorities in charge of war invalid welfare, preferred to find more permanent jobs for war invalids, which would offer them employment also in peacetime.

In principle, providing war invalids with jobs was regarded as the main foundation for re-integrating these men into civil life. The resistance shown by quite a few of the injured, who found they “had had their bones shot to pieces for the state […] and so now they should also be kept by the state” was rigorously opposed by the authorities: it was argued that only by cheerful acceptance of work could an invalid prove eligible to be provided for by the state.

It was natural that the reduced capacity to work of these persons also gave rise to the idea of accommodating war invalids separately in their own trade and production cooperatives for invalids, where they were not confronted with competition from able-bodied workers. However, the first experiments of this nature did not extend beyond the character of pilot projects. There was no money. The same applied to the garden settlements proposed by the Kriegerheimstättenbewegung (movement for homesteads for returning soldiers); intended to accommodate returning soldiers, they would also include self-provision. People asked themselves everywhere whether it would be better to group war invalids together so they could bear their fate together, or whether this would exacerbate their exclusion from the rest of society. War invalids themselves often had their own ideas of how to earn their living and applied in many cases for less demanding jobs as janitors or in state provision posts. Tabaktrafiken, the state tobacco shops, were also popular. They were traditionally and preferentially given to war invalids, especially those blinded in the war.

After the war the Employment of Invalids law regulated the accommodation of war invalids on the job market; it was the direct predecessor to the present-day Austrian law for the employment of persons of disability.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Healy, Maureen: Civilizing the Soldier in Postwar Austria, in: Wingfield, Nancy M./ Bucur, Maria (Hrsg.): Gender and War in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe, Bloomington/Indianapolis 2006, 47-69

Quotes:

“had had their bones shot to pieces …“: Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, AT-OeStA/AdR BMfsV Kb, Kt. 1357, 2748/1918, AV Troppau v. 14.7.1917 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Invalid pensions, allowances for wounded veterans, state support and maintenance contributions

- The failure of private welfare

- The hospitals

- From recovery to reintegration: the training of invalids

- Work for war invalids

- Heroes or victims? War invalids and their impact on general awareness

- Forms of war injury

- Discontent and misery: war invalids get organised