-

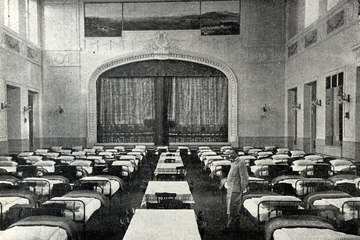

Invitation to an event for the benefit of the Invalids School in the No. 11 Vienna Reserve Hospital, poster, 1915

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

Wounded soldiers in the War Dental Clinic of the IVth Army in Lublin, photo, 1915–1917

Copyright: Zahnmuseum Wien

After being wounded, the soldiers now had to endure what were frequently months of roaming from one hospital to another in the hinterland. Many of these facilities could make no more than provisional arrangements to care for the invalids.

First aid for the war-injured and ill soldiers was given in the field hospitals. From here they were transferred to the hospitals and sanatoriums located in the hinterland. Existing hospitals were adapted and enlarged to accommodate them – often by adding barrack-type buildings; schools, universities, children’s homes, museums and other facilities were also converted into soldiers’ hospitals. If possible, the attempt was made to accommodate war invalids needing prolonged medical treatment in their home countries in the Monarchy and to place them in specialist institutions according to injury. Since in theory there was always the chance of being healed, wounded and sick soldiers were at first not declared unfit for service, thus they were not released from military service and remained subject even as patients to military command. They might be transferred from one hospital to the next until being declared unfit for service and in case of recovery could be commanded back to the front at any time or to a service post in logistic support in the rear areas. The military remained responsible for providing for the infirm for a full year, before this was taken over – if treatment actually lasted that long, which was not a rare occurrence – by the Landeskommissionen zur Fürsorge für heimkehrende Krieger (State committees for the welfare of returning soldiers) established in early 1915, and thus into civil responsibility.

The hospitals were of very varying quality. Medical care was not state of the art everywhere. In more remote parts of the Monarchy it was not a rare occurrence that provision of food and heating materials was very difficult to procure. In contrast, in Vienna there were several modern hospitals set up as paragon institutions that could boast astonishing medical achievements, especially as regards surgery and orthopaedics. First and foremost here was the Reserve Hospital No. 11 with its training workshops in Vienna X, Schleiergasse 17, set up by the military administration in 1915 on the initiative of the orthopaedist Hans Spitzy. By mid-1918, around 24,000 soldiers were being cared for here.

Nevertheless, the greatest deficiencies were experienced in hospitals and sanatoriums for tuberculosis patients, who formed a considerable proportion of war invalids. While the Styrian state committee for the welfare of returning soldiers in late 1915 already availed of 800 hospital beds for invalid soldiers and another 800 for TB patients, in 1917 Upper Austria for instance still did not have a single institution for the treatment of tuberculosis.

Many war invalids spent months and years in the hospitals. Not a few found themselves completely uprooted in such institutions after the war, which were ultimately also the places where the organisation of war invalids into their own influential associations and societies was initiated.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Barth-Scalmani, Gunda: Kranke Krieger im Hochgebirge: Einige Überlegungen zur Mikrogeschichte des Sanitätswesens an der Dolomitenfront, in: Mazohl-Wallnig, Brigitte/Kuprian, Hermann J. W./Barth-Scalmani, Gunda (Hrsg.): Ein Krieg, zwei Schützengräben. Österreich-Italien und der Erste Weltkrieg in den Dolomiten 1915–1918, Bozen/Innsbruck 2005

Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2002

Weitensfelder, Hubert: Prothesen sammeln, in: Steinbrener, Christoph (Hrsg.): Unternehmen Capricorn. Eine Expedition durch Museen, Wien 2001, 54-61

-

Chapters

- Invalid pensions, allowances for wounded veterans, state support and maintenance contributions

- The failure of private welfare

- The hospitals

- From recovery to reintegration: the training of invalids

- Work for war invalids

- Heroes or victims? War invalids and their impact on general awareness

- Forms of war injury

- Discontent and misery: war invalids get organised