-

-

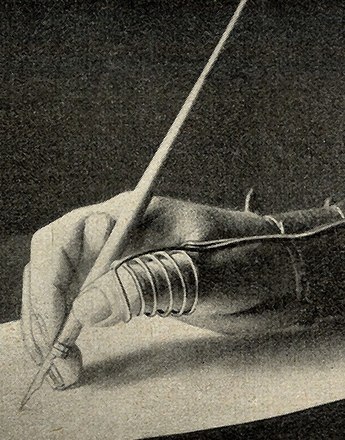

The armour made of nails of the Vienna Iron Wehrmann, photo

Copyright: Harald Wendelin

-

Speech by Emperor Franz Joseph to the benefit of the Imperial-Royal Austrian Military Widows and Orphans Fund, sound recording, 14 December 1915

Copyright: Österreichische Mediathek

Partner: Österreichische Mediathek

The many welfare measures organised with good intentions by private associations to help war invalids and war widows were more propagandist than of real value.

Private welfare was much challenged, confronted as it was by the lack of overall state provision for war victims. Numerous associations and funds actually did contribute to war provision right at the beginning of the war and were able to collect significant amounts at the start. Afterwards, however, the readiness of the population – itself in need – to donate waned more and more as the war wore on, and the failure of private welfare became clear. Even support from the very highest echelons of society could not prevent this.

Among the many activities initiated by the private sector the Nagelaktionen (nail actions) were among the most original ideas. The idea of driving nails into the wooden figure of a medieval knight and giving a donation for each nail for the relatives of fallen soldiers was the brainchild of the Militär-Witwen- und Waisenfonds (Military Widows and Orphans Fund), which enjoyed the particular support of the emperor. The knight was nailed for the first time on 6 March 1915 on Schwarzenbergplatz in the presence of prominent personalities. In just one week 11,000 Viennese had followed the example of Archduke Leopold Salvator, who along with the ambassadors of the German Empire and Turkey had hammered in the first nails. The wooden knight was covered with an armour consisting in all of about 500,000 nails, which brought in a revenue of more than 700,000 kronen. Lively business was done with postcards, badges and small soldier statuettes to support the action. Consequently, patriotic fervour gripped many other places in the Monarchy and also the German Empire, so that everywhere nailed figures, military signs, coats of arms, submarines, tanks, eagles and other emblems joined the repertoire. Regiments, professional organisations and schools imitated the Viennese action. But after only one year the action, initiated with such pomp, had subsided into inertia.

Less effective in publicity but all the more extensive were the activities of the Gesellschaft zur Fürsorge für Kriegsinvalide (Society for the Welfare of War Invalids). This private society, which ran a private carpentry for invalids in Vienna, was chosen by the Ministry of the Interior to care for those war invalids who – particularly the gravely wounded – could not find their feet in the job market. Conceived as a large society with a constitution and branches across the whole Monarchy, nevertheless, the society did not manage to extend its sphere of influence beyond Vienna. In 1917 it could manage no more than find jobs for 47 war invalids.

So important as these private measures were on a small scale, so little were they suited to provide feasible solutions for the problem of providing for widows and orphans, or re-integrating war invalids into the work process. It became evident already during the war that the social agendas had to be concentrated in the hands of the state: the founding of the Austrian Ministry for Social Welfare in early 1918 is an expression of this. Also the agendas of war invalid provision were transferred from the Ministry of the Interior to the new social department. But it was now too late to actuate a comprehensive reform of social agendas in the Monarchy.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Fahringer, Franz: Über die Kriegsbeschädigtenfürsorge. Ihre Anfänge und ihr Werdegang in Österreich, Diss. Wien 1953

Hasiba, Wilhelm: 60 Jahre Kriegsopferversorgung in Österreich, o.O. [Wien] 1979

Nierhaus, Irene: Die nationalisierte Heimat. Wehrmann und städtische Öffentlichkeit, in: Ecker, Gisela (Hrsg.): Kein Land in Sicht. Heimat – weiblich?, München 1997, 57-79

-

Chapters

- Invalid pensions, allowances for wounded veterans, state support and maintenance contributions

- The failure of private welfare

- The hospitals

- From recovery to reintegration: the training of invalids

- Work for war invalids

- Heroes or victims? War invalids and their impact on general awareness

- Forms of war injury

- Discontent and misery: war invalids get organised