Yet again capital of the Monarchy: a larger population, more tasks, more bureaucracy, fewer resources

Vienna was bigger than ever before during the First World War and never as big later. There were no censuses held during the war, so there are no secured statistics to analyse, but numerous indications show that the population must have risen to more than 2.4 millions.

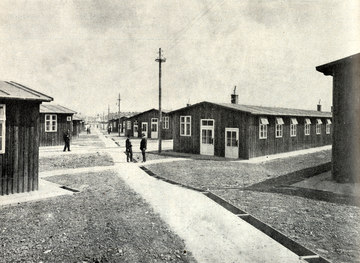

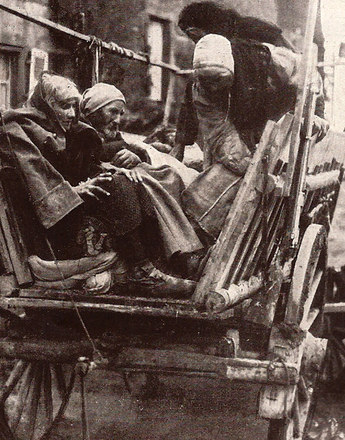

It is one of the paradoxes of the war that Vienna reached its highest population numbers in the whole of its history just at a time when hundreds of thousands of Viennese were away at the front far from their home town. Hotels and guesthouses were overcrowded in the end phase of the war. The chance of renting a flat was practically zero. New arrivals had great trouble finding a place to sleep. The Imperial Residence city was once more a central hub and on a previously unknown scale: Vienna had become a barracks city for soldiers from the entire Monarchy; the central administration for war efforts was now amassed in Vienna. But the city had also been transformed into a hospital city. Alone by March 1915 more than 260,000 wounded had arrived. Most refugees converged on the city, because the capital promised a better chance of survival. After 250,000 refugees and displaced persons landed in Vienna in late autumn 1914, the Government stopped the influx. Vienna became the centre of the war industry and attracted a workforce from the entire Monarchy. All these swarms of people caused the population to climb to over 2.4 millions.

As with most industrial and commercial enterprises, mobilisation in July 1914 also caused a caesura in Viennese municipal administration and operations. In 1914 the numbers of personnel employed by the municipal corporation came to about 43,000 civil servants and employees. Half of all employees from the tram transport system alone were enlisted, 6,000 men. There was an acute shortage in the workforce. Temporary workers were planned to fill the gaps. Starting in 1915, primarily women substituted men, but only as a temporary measure until the men came back from the front. The most popular figure of the “Kriegsfrauendienst” – women’s war service – was the city tram conductress. Pensioned-off civil servants were called back to their workplace. Teachers at schools had to take over other tasks besides their classes, for instance the complex job of issuing rationing cards.

The planning, issuing and control of bread, potato and various other cards was only one of the many new tasks crowding in for the city authorities to handle. In many other spheres, too, the city had to provide for more resources to became available so as to cope to some degree with the urgent problems and acute requirements. The quantitative numbers quoted in the administration report on wartime show clearly that the administrative handling of monetary and practical welfare alone placed civil servants under extreme pressure. An abundance of new authorities was set up: the municipal youth office, the war invalid office, the housing office, the municipal health office, the workers’ welfare office, the milk provision department, the department food welfare actions, the war kitchen commissariat, the advisory office for private affairs of enlisted persons, the central headquarters for war refugee welfare, the municipal headquarters for tuberculosis welfare, and so on and so forth. The new official building on Felderstrasse opposite the Town Hall was already full when not a single light bulb had been installed to illuminate the corridors.

Work conditions deteriorated in many regards. The increasing cost of living fretted away a major part of people’s wages. Civil servants had to move together, office rooms were scarcely heated, light was saved, clothes and shoes couldn’t be replaced. In September 1918 a two-day strike by tram workers demanding higher wages and better welfare provision paralysed public transport throughout the city. Despite this, the newly established war kitchen in the Felderstrasse office building improved matters to a certain degree in daily provisioning.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Beiträge von Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas/Mertens, Christian/Ma-Kircher, Klaralinda/Stekl, Hannes in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013

-

Chapters

- Wartime Mayor Richard Weiskirchner

- The political system: The “Obmänner”conference and the municipal council

- Yet again capital of the Monarchy: a larger population, more tasks, more bureaucracy, fewer resources

- “Approvisionierung”

- State, communal and voluntary welfare

- Tenancy protection

- “The Dying City”