Astonishing but imperative as a consequence of the war: the Christian Social municipal government had to assert tenancy protection against its own clientele, the house owners. Tenancy protection was not the only social achievement to be continued by “Das Rote Wien” – Red Vienna.

The start of the war exacerbated the notoriously controversial relationship between house owners and tenants. The mayor and district representatives appealed to the proprietors to be generous in their treatment of needy tenants. However, the former behaved according to their tried and trusted formula and wished to give the tenants their notice if rents were not paid. The authorities gradually came to support the legal trick used by many tenants as advised by the “Arbeiter-Zeitung”, the workers’ newspaper: if the husband now serving in the army or territorials had rented the apartment, he was the home owner. The notice of termination had to be sent to him. The wife was not obliged to open the envelope that came from the court. Should the notice be delivered to her she could go to the local district court of law, appeal against it, and inform that her husband was the tenant; what counted was the information on the registration form. The court could commission a trustee for the absent tenant or interrupt proceedings until the husband returned.

To ameliorate this conflict, the provided maintenance contributions for women and families of the enlisted soldiers accounted the rent of the home separately, but only to around 50 – 60 percent of the full rent. If due rent was not paid, house proprietors gained deductions in real estate tax from the Ministry of Finance. Interventions by the strongly frequented communal housing welfare department was also effective in helping the needy and unemployed. Despite this, many court proceedings remained pending in which house owners had brought a charge for non-payment of rent. Jurisdiction and also the supreme court usually decided on the side of the tenant. Eviction stopped almost completely. The number of notices of termination dropped to around a third of the pre-war statistic.

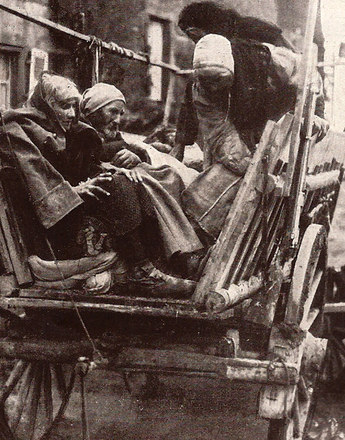

Mobilisation caused homes to become free, and empty properties multiplied, however, the influx of refugees, the prospering war industry and the proliferation of bureaucracy drastically decreased the number of available homes. The galloping increase in the cost of living which also affected rents triggered a debate about rent prices. The Social Democrats were by no means the only faction to demand a freeze in rents and a fixing of them by the authorities in order to combat growing impoverishment. At the same time the authorities wanted to take legal action to force the compulsory renting of empty properties. And it was becoming more and more difficult to move house because the prices for removal services with a vehicle were exploding, and ultimately it became impossible even to organise a horse and wagon. The old system of frequent “flitting” collapsed before the people’s very eyes.

On 8 December 1916, a separate housing office was set up by the Vienna Corporation. The first of a series of tenancy protection regulations was issued on 28 January 1917, retro-active to 1 January 1917. Rents were frozen. Starting in October 1918, a separate department of the “war usury office” dealt with illegal practices in housing. In late October 1918 the ordinance was issued announcing the unlimited validity of tenancy protection. What had started as an emergency action in the war and limited to wartime was codified in the tenancy protection regulations of 1922 with the introduction of so-called peace rent prices. And even the council housing scheme of “Das Rote Wien” was anticipated in announcements by Mayor Weiskirchner.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas: Wohnverhältnisse und Mieterschutz, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 462-469

-

Chapters

- Wartime Mayor Richard Weiskirchner

- The political system: The “Obmänner”conference and the municipal council

- Yet again capital of the Monarchy: a larger population, more tasks, more bureaucracy, fewer resources

- “Approvisionierung”

- State, communal and voluntary welfare

- Tenancy protection

- “The Dying City”