-

The refrigerated warehouse of the City of Vienna, photograph

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

Bread and flour ration card, issued by the Municipality of Vienna, 1915

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall

Provisioning with food and energy, the so-called “Approvisionierung”, was the Achilles heel of the city in the dramatic years 1914 to 1918. Vienna was condemned to suffer hunger and cold. The picture of hundreds of thousands queuing became the symbol of the age.

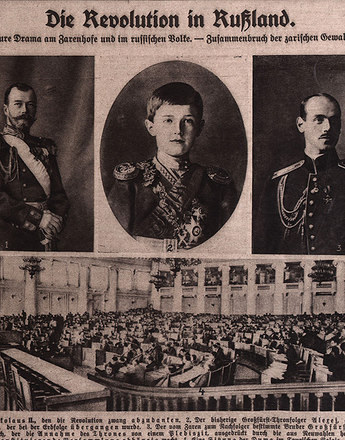

When vegetables and potatoes became dearer at the start of the war, in August 1914 women devastated the market stalls on Yppenplatz. One year later the situation escalated in many places in front of shops and in the markets. Every day hundreds of thousands (police reports state between 300,000 and 500,000) stood in queues in horrendous conditions in order to claim their ration of bread, a morsel of meat, or a couple of eggs. Anyone who didn’t join them was in danger of getting nothing at all. The authorities tried to forbid queuing, mayor and municipal politicians took measures against it – but to no avail. Queuing became a symbol of this war. In late autumn 1916 a new political dimension came into play. Now the employees of occasional firms intervened in order to force food delivery. They went on strike, marched into the inner city with demands for bread and adequate food. Lads played cat and mouse with the police. Shoe shops were stormed, baker’s vans attacked, butcher shops plundered. Year by year, the allocated rations became smaller and the hunger greater, the population was obliged to “fast”. Reports of the February Revolution in Russia had an electrifying effect; the slogan “Bread and Peace” became rife throughout Vienna as well. The mass strikes in January now sparked off panic in Government and emperor more than ever, fuelling the temptation to impose a state of emergency. The front was now finally encroaching upon the hinterland, the home front. City and government attempted to counter the distress and threat of revolution by giving social politics a boost (tenants’ rights, war kitchens, war gardens) and by organising provisions and welfare (cards for bread, coal, petroleum, potatoes, etc.).

The beginning of the war had already exposed the weaknesses of the provisioning system, especially shortages of flour, meat, potatoes and fodder, also coal supplies. On the one hand, supplying of goods was reduced. Particularly exports from Hungary – the source of more than fifty per cent of food before the war – were cut back in part to a sixth of the pre-war level. The connection to Galicia as grain supplier also broke down. All this was exacerbated by the transportation problem: the prioritisation of military transport meant that civilian requirements were set back, particularly prior to offensives; for weeks, the state railways were almost exclusively reserved for the needs of the army. The city mobilised what and where it was able: it placed the tram system with freight wagons in the service of civilian provisioning, shored up coal supplies with sixty two-horse wagons from the city’s horse-and-cart facilities.

Mayor Richard Weiskirchner found himself once again in a complicated competency structure. On the one hand, the municipal corporation enjoyed relative autonomy in decisions made in its independently operating sphere; on the other hand, it was subordinate to the direct central administration, thus in the delegated area of effectiveness it had to perform decrees from the State Government and the Lower Austrian Provincial Governor. Time and again Weiskirchner endeavoured to influence the Lower Austrian government office and the state government, firstly in order to gain concrete support, secondly to push through desirable decrees and ordinances. For instance in autumn 1914, the introduction of top prices was negotiated for flour and grain throughout the entire Monarchy. But this kept colliding with the resistance of the government and the military. The highest prices solely valid for Lower Austria (announcement of 31 August 1914) had the fatal consequence that supplies to Vienna functioned even less, the products simply disappeared from the market. It was the profound distress of the so-called “Swedish Turnip Winter” (Steckrübenwinter) and the reductions in bread and flour in January 1918 that led the city to the brink of collapse.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Beiträge von Healy, Maureen/Mertens, Christian/Berger, Peter/Langthaler, Ernst in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 336-347

Hautmann, Hans: Hunger ist ein schlechter Koch. Die Ernährungslage der österreichischen Arbeiter im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Bewegung und Klasse. Studien zur österreichischen Arbeitergeschichte, Wien 1978, 661-681

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I. Cambridge 2004

Loewenfeld-Russ, Hans: Die Regelung der Volksernährung im Kriege. Wien 1926 (Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte des Weltkrieges)

-

Chapters

- Wartime Mayor Richard Weiskirchner

- The political system: The “Obmänner”conference and the municipal council

- Yet again capital of the Monarchy: a larger population, more tasks, more bureaucracy, fewer resources

- “Approvisionierung”

- State, communal and voluntary welfare

- Tenancy protection

- “The Dying City”