Starting the war was easy. But ending the war seemed to be an impossibility. The population no longer wished to hear anything about the war after the “Swedish Turnip Winter” of 1916/17. The Imperial Capital and Residence sank into a vortex of apathy and aggression, dirt and social ignominy.

The Viennese populations was visibly marked, most of them long undernourished, clothes and suits no longer fitted; there was a strong demand for antidotes against itch mites; shoes and leather soles were hot property, doctors diagnosed deficiency diseases. Children went barefoot even in the cold seasons. Country communities warned on posters that “Hamsterer” – scroungers – trippers and summer visitors from Vienna were undesirable; occasionally these were prevented with savage brutality. The Viennese populace felt imprisoned, forgotten by government and administration. Invalid veterans became vagrants on the hunt for alms. The atmosphere was aggressive, complaints about war-related rudeness were ubiquitous, consideration and courtesy were left by the wayside in the fight for survival. Automobiles and fiacres had disappeared from the streets, shop windows yawned empty, many goods were no longer available. Notices on restaurant doors read “Closed till the end of the war”. Apart from a few exceptions, all building work had stopped; scarcely any renovations were carried out for four and a half years. So much of what was projected, planned or ripe for development before 1914 could no longer be started, let alone finished. Plans for constructing the Underground railway system, the new municipal museum on “die Schmelz” and the magnificent building of the Austrian-Hungarian Bank on the grounds of the former Bosnia Barracks on Alserstrasse had to be shelved. The start of the war sliced an epochal caesura through the illustrious history of building in Vienna. The social agenda had priority.

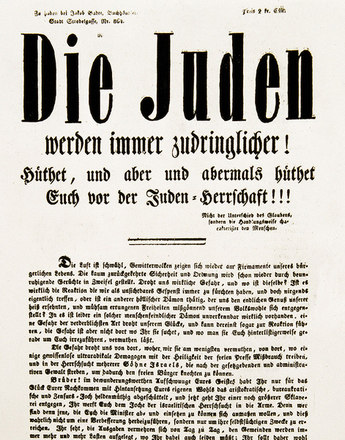

The longer the war lasted, the more intense the polarisation in Vienna. An incident in the Rathauskeller in early May 1918 was a small brick in the great crumbling edifice of nationality conflicts: because Czech Imperial Council members and other high-ranking representatives from Brno spoke Czech, they were expelled from the restaurant. The brawl had its consequences: the Czech MPs requested the Prime Minister temporarily to refrain from ordering potato deliveries from Moravia to Vienna. The pressure noticeably rose in Vienna’s social and political structure. In the German People’s Diet in June 1918 Mayor Weiskirchner demanded anti-Slavic measures and a political scene in general which acknowledged that “it is the rightful due of the Germans that they take on the leading role in the empire.” Anti-Semitic feelings exploded: Jews were blamed for the war, the rise in the cost of living, the Spanish ‘flu and more, and administrative chicanery did much to sour their life in the capital. They were castigated in the Vienna Municipal Council, Jewish refugees from Galicia should be made to return promptly to their homeland. The middle classes cast envious eyes on the workers, who fought for higher wages and better working conditions by going on strike.

From 1915 on, the situation in the city for children and young people was described as extremely critical. In many cases the fathers were on the front, mothers at work. Children were forced into the role of parents, could not be supervised, roved wild through the city. 80 percent were marked by hunger after the war. The pictures of Viennese children and their misery horrified the whole of Europe after the war and caused aid organisations to haste into the city. The anxiety about the future generation was the major topic of the day. The corporation administration set up a separate Youth Office. Countless organisations worked at the task of rescuing the children from distress, misery and neglect; they fed them as best they could and at least in summer tried to give them some fresh air in day homes, summer camps and evacuation to the country.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Pfoser, Alfred: Wohin der Krieg führt. Eine Chronologie des Zusammenbruchs, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 580-686

-

Chapters

- Wartime Mayor Richard Weiskirchner

- The political system: The “Obmänner”conference and the municipal council

- Yet again capital of the Monarchy: a larger population, more tasks, more bureaucracy, fewer resources

- “Approvisionierung”

- State, communal and voluntary welfare

- Tenancy protection

- “The Dying City”