-

The Committee of the Women's Aid Campaign in the War, with Richard und Bertha Weiskirchner; photograph

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall -

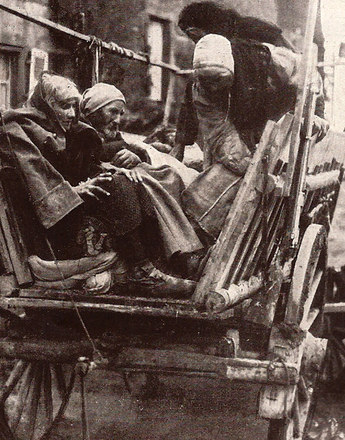

Anita Müller’s soup and tea kitchen for refugees in Leopoldstadt, Vienna, newspaper photo

Copyright: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

Partner: Wienbibliothek im Rathaus – Vienna Library in the City Hall

Society was programmed to expect a short campaign but not an enduring war. The social agenda became more and more urgent. The war marked the dawn of the modern social state.

Already in the evening of 25 July 1914 after the expiry of the ultimatum, the Mayor of Vienna Richard Weiskirchner announced he would do everything to see that relatives of enlisted soldiers would be given their due financial support. This was specified in the war maintenance law of 1912. The maintenance amount was compounded of maintenance payments and house-rent contributions. Those liable to claim welfare were primarily the wife and the legitimate progeny, but also – depending on individual cases – forbears, siblings and parents-in-law. The law offered great scope for interpretation, which resulted in chaos. An added problem was that in many working-class families prior to 1914 women were forced to go out to work because the husband’s income was not sufficient. It also affected the wives of tradesmen, who ran the business alone after their husbands had been enlisted. Through their independent gainful employment they forfeited the maintenance, at least according to law. Conflicts were pre-programmed, and complaints soon followed. Moreover, people were outraged that the maintenance amounts were not adapted to the increasing cost of living. The lack of state support was a source of rebellious and revolutionary mood among women, at any rate in the second half of the war.

The corporation was also overtaxed by the state maintenance contribution in the context of the transferred field of action. The application for maintenance had to be submitted to the district offices; here an inquiry was carried out as to the legitimacy of the claim. Decisions were made in the twenty maintenance commissions of the Lower Austrian Government Office, where the Vienna municipal corporation had one representative in each. Distribution of money was organised in eleven districts by way of the municipal chief cashiers’ departments. What was deemed to be a civic service at the beginning of the war turned out to be a boomerang for the city as the war wore on. It was the institution responsible for the rancour of all those women drawing maintenance contributions. Twice a month, women had to queue in degrading conditions at the municipal cashiers’ offices in order to pick up their meagre support. The statistics are impressive: in October around 60,000 persons were registered; this grew incrementally by a group of dependents that included interned persons, refugees, invalids, etc. By the end of the war 650,000 persons were registered for picking up social support.

Besides the legal maintenance contributions, a special war welfare fund of the City of Vienna was set up for families and individuals in distress, for starving and abandoned children, and a major advisory and support network was created for women. Advance and supplementary payments were granted on top of the legal support amount, money poured out for those cases of hardship where there was no legal claim for payments, and practical material help was organised (e.g. jobs for needy, unemployed women and war kitchens). Communal war welfare was organised to function with divided responsibilities. Private organisations raised money and donations in kind, the City Government provided for just distribution and control, and supported the agenda with their own money or payments in kind. Voluntary and honorary organisations were yet again integrated on site in the practical implementation of war welfare. Again, the statistics are impressive: in 1918, around 200,000 registered families with 700,000 so-called persons “of small means” were issued cheapened shopping tickets; in the so-called war kitchens more than 45 million portions were cooked in the second half of 1918, giving the needy food at least once a day. Countless independently active initiatives provided welfare, besides the state and the corporation.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Die Gemeinde-Verwaltung der Stadt Wien vom 1. Jänner 1914 bis 30. Juni 1919 unter den Bürgermeistern Dr. Richard Weiskirchner und Jakob Reumann, hg. vom Wiener Magistrat, Wien 1923

Ein Jahr Kriegsfürsorge der Gemeinde Wien, hg. von der Stadt Wien, Wien 1915, 54-56

Hauptmann, Manuela: Frauenprotest und Beamtenwillkür, in: Österreich in Geschichte und Literatur 56 (2012), Heft 3, 247-271

Weigl, Andreas: Kommunale Daseinsfürsorge. Zur Genesis des ‚Fürsorgekomplexes‘, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 336-347

-

Chapters

- Wartime Mayor Richard Weiskirchner

- The political system: The “Obmänner”conference and the municipal council

- Yet again capital of the Monarchy: a larger population, more tasks, more bureaucracy, fewer resources

- “Approvisionierung”

- State, communal and voluntary welfare

- Tenancy protection

- “The Dying City”