Following the first general, equal, direct and secret Imperial Diet elections held in 1907, the Christian Socials entered the House of Deputies as the strongest party.

With 66 deputies (13%) they were initially just behind the Social Democrats, who won 87 seats (17%). By the end of June, however, the Christian Social Party had joined with the conservative Catholic People's Party to create the Christian Social Imperial Party, whose 96 deputies (19%) made it the largest group in the Cisleithanian Imperial Diet.

Following an initial consolidation phase, it developed into a party that was loyal to the state, with an increasingly conservative ideology and Catholic image. It adjusted its anti-capitalist position towards support for the idea of state capitalism and it strove to uphold the monarchy by achieving a balance between national and class-specific interests. Its social reform approaches took second place, and only little remained of its commitment to the creation of a corporate order.

Since 1894, the Reichspost had served as the Christian Social organ. Through the Cartel Association (student fraternities) and the Leo Society, Austrian Association of Christian Scholars and Friends of Knowledge founded in 1892, encouragement was given to Catholic education and science. Mention should also be made of the municipal achievements of the Christian Socials in Vienna. The gas and electricity works and the public transport system were acquired by the City of Vienna, public parks were created, welfare institutions, hospitals and public baths were built.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the political agenda was dominated by crises of the Habsburg Empire and the nationalities problem. At the 1905 Eggenburg Party Conference, the Christian Socials resolved to support the re-founding of the Empire on the basis of the autonomy of the various nationalities as a means of preserving the Habsburg Monarchy.

The shift of focus towards conservatism led to an increase in the influence of the conservative, property-owning and agricultural classes, the peasantry and the business classes within the party. Karl Lueger reacted to this in his political testament as follows: "The party should therefore take care not to become the party of a specific profession, it should be neither an agricultural nor another specific party but it must direct its attention both to the metropolitan population and intelligentsia and to the peasantry."

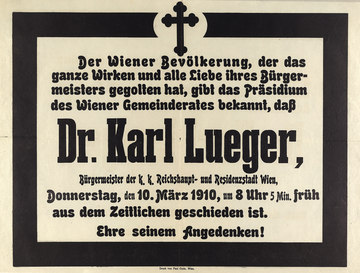

Lueger died on 10 March 1911, and the rivalries between the contenders for the succession and internal accusations of corruption plunged the party into a serious crisis. At the Imperial Diet elections held in June, it suffered a major defeat, losing its leading position in the capital. However, this latter fact did not have any direct consequences, since there were no further elections to the Vienna City Council before the end of the Habsburg Monarchy. Until then, the office of Mayor of Vienna was held by the Christian Social politician Richard Weiskirchner. Nevertheless, the Christian Socials were already losing their support amongst the Vienna population, the metropolitan proletariat clientele gradually being alienated by the party's shift towards a petty bourgeois and middle class party characterised by social conservatism and loyalty to the state.

Translation: David Wright

Berchtold, Klaus: Österreichische Parteiprogramme 1868-1966, Wien 1967

Hanisch, Ernst/Urbanitsch, Peter: Grundlagen und Anfänge des Vereinswesens, der Parteien und Verbände in der Habsburgermonarchie, in: Rumpler, Helmut/Urbanitsch, Peter (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848-1918. Bd. VIII. Politische Öffentlichkeit und Zivilgesellschaft. 1. Teilband. Vereine, Parteien und Interessenverbände als Träger der politischen Partizipation, Wien 2006, 15-111

Kriechbaumer, Robert: Die großen Erzählungen der Politik. Politische Kultur und Parteien in Österreich von der Jahrhundertwende bis 1945, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2001

Rumpler, Helmut: Österreichische Geschichte 1804-1914. Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie, Wien 1997

Urbanitsch, Peter: Politisierung der Massen, in: Das Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs. 2. Teil 1880-1916. Glanz und Elend (Ausstellungskatalog der Niederösterreichischen Landesausstellung im Schloss Grafenegg), Wien 1987, 106-118

Wandruszka, Adam: Österreichs politische Struktur. Die Entwicklung der Parteien und politischen Bewegungen, in: Benedikt, Heinrich (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Republik Österreich, Wien 1977, 289-486

Wandruszka, Adam: Die Habsburgermonarchie von der Gründerzeit bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Das Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs. 2. Teil 1880-1916. Glanz und Elend (Ausstellungskatalog der Niederösterreichischen Landesausstellung im Schloss Grafenegg), Wien 1987, 4-19

Wandruszka, Adam: Parteien und Ideologien im Zeitalter der Massen, in: Schulmeister, Otto (Hrsg.): Spectrum Austriae. Österreich in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 2. Auflage, Wien et al. 1980, 167-180

Quotes:

"The party should therefore take care …“: Karl Lueger, Politisches Testament, quoted from: Wandruszka, Adam: Die Habsburgermonarchie von der Gründerzeit bis zum Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Das Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs. 2. Teil 1880-1916. Glanz und Elend (Ausstellungskatalog der Niederösterreichischen Landesausstellung im Schloss Grafenegg), Wien 1987, 17 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Preconditions and beginnings of political participation

- On the road to political participation

- Liberalism and conservatism

- The rise and fall of liberalism

- Workers unite!

- Party of the masses

- Between a truce policy and left-wing radicalism

- Karl Lueger and the "Sausage Pot Party"

- "The Colossus of Vienna"

- Rise and fall

- Commitment to the Monarchy

- "Greater German", "Smaller German" or "German National"?

- "German and loyal, outright and true"

- "Prussian plestilence" or Habsburgophilia

- The battle for the 'national electorate'