-

The Emperor's tent at the procession in homage to the Emperor on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the reign of Emperor Franz Joseph on 12 June 1908

Copyright: ÖNB Bildarchiv

Partner: Austrian National Library -

Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz: Lemberg/Lviv – The Emperor receives a petition, drawing, 1898

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H.

Partner: Schloss Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. -

“Viribus unitis”, anniversary correspondence card, 1914

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller / Objekt aus Privatbesitz

-

Austrian national anthem, “Gott erhalte”, sound recording, around 1914

Copyright: Österreichische Mediathek

Partner: Österreichische Mediathek -

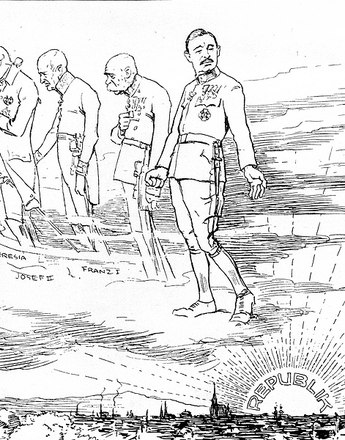

Hans Götzinger: On 18 August, illustration, 1908

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller

Emperor Franz Joseph was the symbol par excellence of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. For most of his subjects the Emperor was a sacrosanct figure who deserved their utmost respect. He had been on the throne since 1848 and for one and all was simply ‘the Kaiser’.

To be a citizen of the Monarchy also meant being a subject of the Emperor. All reforms notwithstanding, the Monarchy was primarily an authoritarian state, embodied in the person of the Emperor: when court judgments were pronounced, laws passed or honours bestowed, all these things and many more were done ‘in the name of His Majesty’.

The Emperor was ubiquitous. His portrait adorned the walls of every office and every classroom throughout Monarchy. He enjoyed an exalted public image and in any kind of celebration his name and person were invoked as symbols of the unity of his realm. Franz Joseph was the subject of a veritable patriarchal cult that presented him – with the help of various symbolic back-ups such as the Radetzky March – as a father-figure to the Monarchy as a whole.

The myth surrounding the Emperor certainly served to reinforce the fabric of the state. Thanks to his exceptionally long reign – at the outbreak of war in 1914 he was in the sixty-sixth year of his reign, which was finally to last almost sixty-eight years, the longest of any Habsburg monarch – Franz Joseph had indeed been a symbol of permanence and stability for the crisis-prone Dual Monarchy. The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and the House of Habsburg-Lorraine were rooted in a dynastic idea of which Franz Joseph was the very incarnation. He personified the unity of the multi-national empire and saw himself as a counterweight opposing the centrifugal currents that had been set in motion by the escalating problem of the nationalities.

At the time of the First World War the Emperor was still a political force to be reckoned with, as his power had been safeguarded by the special position guaranteed him in the constitution. Not only, for example, was he very largely responsible for foreign policy but he was given even greater freedom of action by the weakness of Austrian parliamentarism. Governments were appointed by – and were first and foremost answerable to – the Emperor in person. The ageing monarch behaved as if the business of daily politics was beneath his dignity. Governments came and went, overseen by Franz Joseph as their constant patron and guardian.

Personally, Franz Joseph was a convinced adherent of an outdated aristocratic code of honour. The Emperor and the old Austrian nobility were imprisoned in the rites of the past. The court of Vienna was famous for its elegance and social exclusiveness but was also known to be the most elitist of all European courts and incapable of openness towards modern social trends.

While the elderly Emperor was above any kind of personal criticism this was not entirely true of the dynasty. The numerous scandals concerning the ‘supreme Arch-House’ led to increasing criticism of the decadence of certain members of the Habsburg clan, which was all grist to the mill of the idea that the traditional elites were in a state of crisis and decline.

Franz Joseph saw himself as a man of the past, a foreign body in the modern world. As a preserver of what had been passed down to him he was fearful of changes, even when he recognized their inevitability – and as long as he lived, he preferred things to stay as they were. In his old age it was common knowledge that he had grown tired of the responsibilities of his high office. Although he would in principle have been prepared to make way for a successor, the personal conflict with the heir to the throne Franz Ferdinand held him back. ‘If I had a son who inspired me with sufficient confidence, I would gladly abdicate – but for this dangerous fool, never!’

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Beller, Steven: Franz Joseph. Eine Biographie, Wien 1997

Conte Corti, Egon Caesar/Sokol, Hans: Franz Joseph. Im Abendglanz einer Epoche, Wien 1990

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Herre, Franz: Kaiser Franz Joseph von Österreich. Sein Leben – seine Zeit, Köln 1978

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena/Schippler, Bernd: Schwarzbuch der Habsburger. Die unrühmliche Geschichte eines Herrscherhauses (2. Auflage, ungekürzte Taschenbuchausgabe), Innsbruck [u.a.] 2010

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Traum und Wirklichkeit. Wien 1870–1930. Katalog der 93. Sonderausstellung des Historischen Museums der Stadt Wien 1985, Wien 1985

Das Zeitalter Kaiser Franz Josephs – 2. Teil: 1880–1916. Glanz und Elend. Katalog der Niederösterreichischen Landesausstellung auf Schloss Grafenegg 1987, Wien 1987

Quotation:

‘If I had a son ...': Kaiser Franz Joseph, quoted from: Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005, 559 (translation)

-

Chapters

- ‘God preserve Him, God protect Him’ – The Emperor

- The Army: Austria-Hungary in its entirety

- The bureaucracy as the long arm of the state

- The Dual Monarchy: two states in a single empire

- ‘Indivisible and inseparable’ – the supranational state

- The Habsburg Monarchy in the process of democratization

- The absence of political culture

- A strong monarch and autocratic tendencies