The Austrian version of constitutionalism called for a strong emperor with a comparatively weak role being assigned to the people’s representatives.

‘The divine duty imposed on rulers is to lead their peoples, and if these peoples – as in our monarchy – are not mature enough to act reasonably, they must be compelled to do so. Imposition and force are justified even if they restrict the rights of the people.’

Quoted in Jean-Paul Bled, Franz Ferdinand. Der eigensinnige Thronfolger (Vienna, 2013), p. 219, original quotation in Robert A. Kann, Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand Studien, (Munich, 1976), p. 186

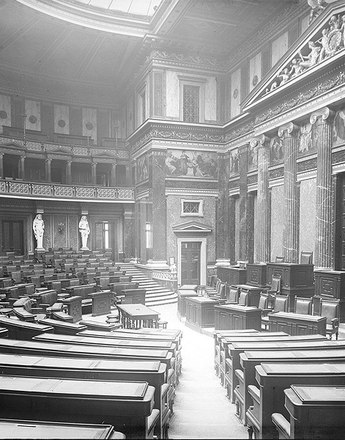

‘I know what I have done; I did not act anti-patriotically.’

The December Constitution of 1867 finally turned the Habsburg Monarchy into a constitutional monarchy, which restricted the absolute power of the monarch. The Austrian parliament or Reichsrat was built on shaky foundations, however, because it was merely entrusted with ‘participation in the legislative and administrative right of the monarch,’ as it was formulated revealingly in the book Österreichische Bürgerkunde published in 1911. In the Habsburg Monarchy the constitution was approved by the Emperor, who passed on some of his power to parliament through it. The extent of parliament’s rights was precisely described in the constitution – everything else was in the absolute power of the Emperor. Franz Joseph also reserved the right of repeal, since the constitution stemmed from his imperial authority and not from the sovereignty of the people.

This was the big difference to a parliamentary monarchy as was traditional in Great Britain, for example. The parliament there represented the sovereignty of the people, which granted the monarch precisely defined and generally symbolic rights as head of state.

The powerlessness of the Austrian parliament, which hamstrung itself through the all-pervasive nationality conflicts, became increasingly evident. The lack of respect for parliamentarianism, due not least to the appalling political culture that prevailed in the Reichstag, is clearly hinted at in an utterance by Foreign Minister Count Ottokar Czernin, who described the parliamentarians quite simply as ‘wasteful baggage’.

To a certain extent, this reflected the basic attitude of the old elites, who sought a return to the monarchic autocracy of neo-absolutism as an antidote to the complicate realities in the era of popular political parties. Extreme conservatives were not averse to the idea of a coup d’état that would invalidate the constitution. They saw the introduction of a monarchic dictatorship as a solution to the political stalemate.

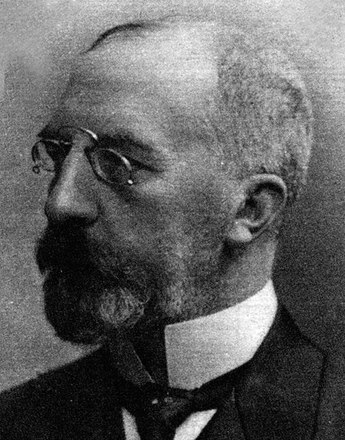

One figurehead in this regard was Minister-President Count Karl Stürgkh, head of the Cisleithanian government from November 1911. His suspension of the Reichsrat in March 1914 was an expression of his conviction that the future of the monarchy could be safeguarded only by a strong imperial regime.

Stürgkh’s assassination on 21 October 1916 by Friedrich Adler, secretary of the Social Democratic party and editor-in-chief of the Socialist magazine Der Kampf, was intended as a signal of opposition to the surreptitious introduction of absolutism.

With the suspension of parliamentarianism and censorship of the media, Adler, son of the Social Democratic party head Viktor Adler, no longer considered that he had any legal possibility of expressing his protest. His trial turned into a political showcase. Adler’s passionate plea was a reckoning with his own party, which he accused of lack of principle, but also a wake-up call for the forces of democracy in Austria, which had become reconciled to the weak parliamentary culture in the country.

Translation: Nick Somers

Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Rumpler, Helmut: Eine Chance für Mitteleuropa. Bürgerliche Emanzipation und Staatsverfall in der Habsburgermonarchie [Österreichische Geschichte 1804–1914, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005

Wandruszka, Adam (Hrsg.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band VII: Verfassung und Parlamentarismus. Teil 1: Verfassungsrecht, Verfassungswirklichkeit und zentrale Repräsentativkörperschaften, Wien 2000

Zitat:

„zur Teilnahme an dem Rechte des Kaisers ...“, zitiert nach: Hanisch, Ernst: Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert [Österreichische Geschichte 1890–1990, hrsg. von Herwig Wolfram], Wien 2005, 230

-

Chapters

- ‘God preserve Him, God protect Him’ – The Emperor

- The Army: Austria-Hungary in its entirety

- The bureaucracy as the long arm of the state

- The Dual Monarchy: two states in a single empire

- ‘Indivisible and inseparable’ – the supranational state

- The Habsburg Monarchy in the process of democratization

- The absence of political culture

- A strong monarch and autocratic tendencies