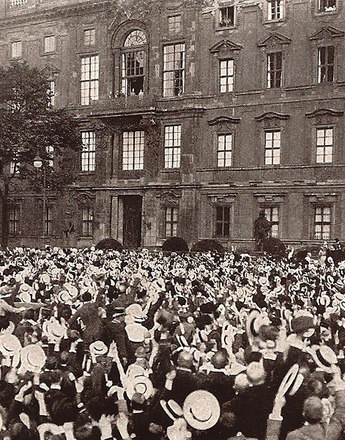

The idea of the all-inclusive enthusiasm for war long dominated the historiography of the First World war. More recent historical research has however unmasked the theory of a euphoria encompassing all classes and political parties as a legend and attests that this view is biased and one-sided.

The press played a pre-eminent role in the 'intellectual' mobilisation for the war and was among the factors responsible for the growth of the legend. There were frequent reports of enthusiastic recruits merrily going off the front wearing their “Tauglichkeits-Sträußerln” – plant and floral sprays as trophies of their fitness to serve. Newspapers were full of photographs and reports of cheering crowds taking their farewells from the soldiers – all certain of victory – with flowers and patriotic songs. Many young people who felt a certain futility in their existence saw an adventure in the war, a welcome opportunity for breaking out of this 'dull life'. Another reason why many young men volunteered to serve in the army was the enhanced revaluation of their masculinity. Those found to be unfit to serve were bitterly disappointed and felt it to be an unbearable disgrace.

But not all people welcomed the war. The reactions to its outbreak were diverse and included affirmation and acceptance but also criticism and rejection. Uncertainty and depression quite considerably tempered the general mood. Philip Schuster, then twelve years old, recounted his memories of August 1914 in an interview: "People cheered them on, giving them courage: […] we’ll soon see one another again! Happy shouting from the people. There were also tears – they should make sure they come back soon! […] The feelings of some were joyful, some afraid, and that’s how the cheering was as well. […] The way the people cheered them off was of course a mixture of fear, joy and fear."

Enthusiasm and jubilation was found less among the working class and in rural districts. Cheering people and patriotic demonstrations were not as noticeable in the smaller towns and villages as they were in larger cities. And the women left at home were frequently beside themselves with anxiety about the survival of the male members of the family, and worries about their own security and existence. For women from the rural milieu the recruitment of the men brought directly threatened the running of their farms, and new demands were made on them in work and efficiency. This is reflected in an excerpt from the war memoirs of Amabile Maria Broz from Trent, translated into German from Italian by Oswald Überegger: "But the first of August was a day that surely no one will ever forget. At seven o’ clock in the morning I saw a bill posted on a building wall calling up all men between the ages of 21 and 40 who had done military service. Oh no! What unhappy news. My brothers came the next day, the second of August. I had to get up at three o’clock in the morning and make breakfast together with my mother. You can’t imagine their appetites! After a few bites they left; they hadn’t the heart to say good bye. I’m now left alone with my aged parents, tormented with grief."

However, critical attitudes or objections to the war had no place in newspaper reports. Censorship did not permit alternative interpretive patterns and critical points of view, public opinion was brought into line and boosted the enthusiasm for war – the voices of war objectors remained unheard in many cases. Nevertheless, autobiographical texts provide an eloquent testimony that the anxieties about son or husband going off to the front and the fear of what was to come frequently overshadowed the war euphoria. The farmer from Trent Giovanni Zontini noted in his diary: "The train was adorned with flowers, sprays and flags, but thoughts were grave, death did not seem far away. The songs were sad, sad as birds on snow."

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner: Der Erste Weltkrieg – Zeitenbruch und Kontinuität. Einleitende Bemerkungen, in: Dies. (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 15-41

Ferguson, Niall: Der falsche Krieg. Der Erste Weltkrieg und das 20. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart 1999

Geinitz, Christian: Kriegsfurcht und Kampfbereitschaft. Das Augusterlebnis in Freiburg. Eine Studie zum Kriegsbeginn 1914, Essen 1998

Hofer, Hans-Georg: Effizienzsteigerung und Affektdisziplin. Zum Verhältnis von Kriegspsychiatrie, Medizin und Moderne, in: Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 219-242

Leidinger, Hannes/Moritz, Verena: Der Erste Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2011

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Sauermann, Eberhard: Literarische Kriegsfürsorge. Österreichische Dichter und Publizisten im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar, 2000

Steininger, Rolf: Einleitung: „Gott gebe, daß diese schwere Zeit bald ein Ende nimmt.“ Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2011, 7-25

Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002

Verhey, Jeffrey: Der Geist von 1914, in: Der Tod als Maschinist. Der industrialisierte Krieg 1914–1918. Eine Ausstellung des Museums Industriekultur Osnabrück im Rahmen des Jubiläums „350 Jahre Westfälischer Friede“ 17. Mai – 23. August 1998. Katalog, Bramsche 1998, 47-53

Winkelhofer, Martina: So erlebten wir den Ersten Weltkrieg. Familienschicksale 1914–1918. Eine illustrierte Geschichte, 2. Auflage, Wien 2013

Quotes:

"People cheered them on …": Schuster, Philipp: Teils freudig, teils ängstlich [Interview], quoted from: Geinitz, Christian: Kriegsfurcht und Kampfbereitschaft. Das Augusterlebnis in Freiburg. Eine Studie zum Kriegsbeginn 1914, Essen 1998, 182 (Translation)

"But the first of August …": Kriegserinnerungen der Amabile Maria Broz, abgedruckt in: Antonelli, Q./Leoni, D./Marzani, M. B./Pontalti, G. (Hrsg.): Scritture di guerra, Rovereto 1996, 40, quoted from: Überegger, Oswald: Der andere Krieg. Die Tiroler Militärgerichtsbarkeit im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2002, 390 (Translation)

"The train was adorned …": Giovanni Zontini, quoted from: Steininger, Rolf: Einleitung: „Gott gebe, daß diese schwere Zeit bald ein Ende nimmt.“ Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2011, 13 (Translation)