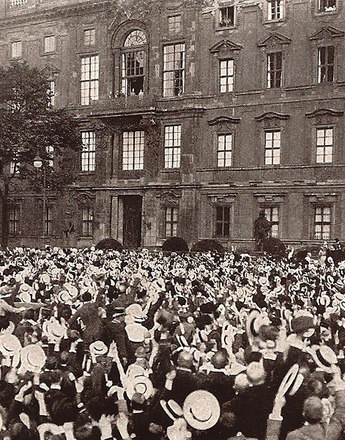

Patent enthusiasm at the outbreak of the war was manifest particularly in intellectual circles, writers, artists, academics, philosophers, scientists, etc. They saw armed engagement as a catharsis, as a cleansing force, as a chance to escape from a pre-war world that had become fatigued and futile.

Many representatives of the artistic-intellectual milieu welcomed the war, among them Anton Wildgans, Georg Heym, Thomas Mann, Georg Trakl, Ernst Jünger, Max Scheler, Hermann Bahr, Georg Simmel, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Rainer Maria Rilke, Robert Musil and Oskar Kokoschka. They didn’t see an apocalypse or downfall in it; they saw change, a hopeful departure into a new and better world, free of decadence, utilitarianism and alienation. The pre-war world seemed mendacious to them, hypocritical, imbued with materialism and a distorted morality. They rejected over-satiated, blasé attitudes and rationalism, and fought against a civilisation that was supposedly blighting everything natural and genuine in the bud. The war would stop or at least partly correct the process of disintegration of culture accompanying industrialisation and the modern age.

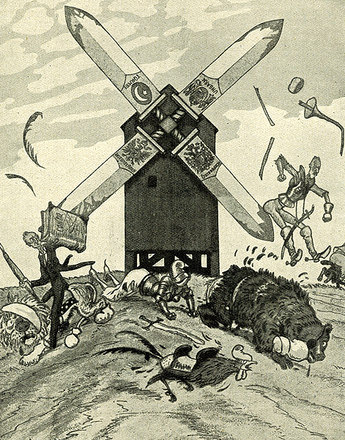

The demand for a warlike conquest of the present was also omnipresent in the arts. It would revolutionise art, bring forth new aesthetic forms and – as Ernst Jünger wrote in his short story Storm – create a new type of human being. "Here an entirely new race bore a new view of the world by marching through an archetypal experience. The war was a primeval mist of spiritual and psychologicall possiblities, pent up with developments."

The abhorrence of the zeitgeist and the hope many intellectuals placed in the outbreak of war are particularly clear in Thomas Mann’s formulation: "We knew it, did we not, this world of peace. Did not vermin of the mind swarm about in it like maggots? Did it not ferment and stink of the decaying matter of civilisation? How could the artist, the soldier within the artist, not praise God for the collapse of a world of peace of which he was so utterly sick? War! We felt cleansing, liberation and a tremendous hope."

There were many scientists, too, who welcomed the outbreak of war – not least based on Darwinist ideas about society. They interpreted the war as a probationary period, which would weed out the weak segments of society and thus contribute to an upgrading of the national collective. "War is a touchstone upon which everything will be eliminated that is sick and rotten", wrote the psychiatrist Karl Baller in 1917 in the Allgemeinen Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie und psychisch-gerichtliche Medizin.

The formula of war as a “major catharsis” was widespread particularly among doctors, psychiatrists and psychologists, who optimistically anticipated that military operations would have a therapeutic effect on the nervous complaints frequently observed in the pre-war period. In their opinion the changes associated with the modern age – increased mobility, urbanisation, mechanisation etc. –permanently damaged the nervous system. Hysteria, neurasthenia and nervous complaints were among the most common diagnoses with which psychiatry endeavoured to describe the psychiatric and mental illnesses of the pre-war generation. Many psychiatrists interpreted the military conflicts as a chance for a society –softened and degenerate in their eyes – to train its nerves and regain control over body and soul. The war, in the diction used by the leading psychiatrist Albert Eulenburg, was a "steel bath […] for nerves that are withering and pining in the dust of long years of peace".

With the outbreak of savage reality however such expectations were bitterly disappointed. The artillery bullets hit the 'genetically valuable' soldiers just as they did the supposedly 'inferior' ones, which is why the mechanised war – thus the new conclusion of many racial hygienists – favoured negative selection. Moreover, the mentally ill and traumatised soldiers emerging in masses already in the first months of the war contradicted the view that the war would be a suitable method of 'toughening up' the nerves and overcoming the "age of nervous ailments".

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Düriegl, Günter: Wir wollen den Traum, wir wollen den Rausch, in: „So ist der Mensch…“ 80 Jahre Erster Weltkrieg. 195. Sonderausstellung Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, 15. September bis 20. November 1994, Wien 1994, 9-14

Eckart, Wolfgang U./Gradmann, Christoph: Medizin im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Spilker, Rolf/Ulrich, Bernd (Hrsg.): Der Tod als Maschinist. Der industrialisierte Krieg 1914–1918. Eine Ausstellung des Museums Industriekultur Osnabrück im Rahmen des Jubiläums „350 Jahre Westfälischer Friede“ 17. Mai – 23. August 1998. Katalog, Bramsche 1998, 203-215

Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner: Der Erste Weltkrieg – Zeitenbruch und Kontinuität. Einleitende Bemerkungen, in: Dies. (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 15-41

Herzinger, Richard: Die grosse Reinigung oder: Weltkrieg für die neue Menschheit. Über die Mobilmachung des deutschen Geistes, in: „So ist der Mensch…“ 80 Jahre Erster Weltkrieg. 195. Sonderausstellung Historisches Museum der Stadt Wien, 15. September bis 20. November 1994, Wien 1994, 15-32

Hofer, Georg: „Nervöse Zitterer. Psychiatrie und Krieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 15-134

Hofer, Hans-Georg: Effizienzsteigerung und Affektdisziplin. Zum Verhältnis von Kriegspsychiatrie, Medizin und Moderne, in: Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 219-242

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Sauermann, Eberhard: Literarische Kriegsfürsorge. Österreichische Dichter und Publizisten im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar, 2000

Schwarz, Peter: „Die Opfer sagen, es war die Hölle.“ Vom Tremolieren, Faradisieren, Hungern und Sterben. Krieg und Psychiatrie in Wien, in: Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien 2013, 326-335

Quotes:

"War! We felt a cleansing …": Mann, Thomas: Gedanken im Kriege, in: Ders.: Politische Reden und Schriften, Frankfurt am Main 1986, 9, quoted from: Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner: Der Erste Weltkrieg – Zeitenbruch und Kontinuität. Einleitende Bemerkungen, in: Dies. (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 19 (Translation)

"Here an entirely new race …": Jünger, Ernst: Sturm, in: Ders.: Sämtliche Werke. Band 15: Erzählende Schriften I, Stuttgart 1978, 27, quoted from, Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner: Der Erste Weltkrieg – Zeitenbruch und Kontinuität. Einleitende Bemerkungen, in: Dies. (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 20 (Translation)

"We knew it…": Mann, Thomas: Gedanken im Kriege, in: Ders.: Politische Reden und Schriften, Frankfurt am Main 1986, 9, quoted from: Kramer, Alan: Dynamic of Destruction. Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War, New York 2007, 163

"War is a touchstone …": Baller, Karl: Krieg und krankhafte Geisteszustände im Heere, in: Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie und psychisch-gerichtliche Medizin (1917), 73, 29, quoted from: Hofer, Georg: „Nervöse Zitterer. Psychiatrie und Krieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 27 (Translation)

"steel bath […] for nerves …": Eulenburg, Albert: Kriegsnervosität, in: Die Umschau (1915), 19, 1, quoted from: Hofer, Georg: „Nervöse Zitterer. Psychiatrie und Krieg, in: Konrad, Helmut (Hrsg.): Krieg, Medizin und Politik. Der Erste Weltkrieg und die österreichische Moderne, Wien 2000, 28 (Translation)