"At last we welcomed with flowers what had been overdue and suppressed for so long."

-

Taking leave of soldiers at the station, photo 1914/15

Copyright: Josef Neubauer

-

“Before leaving Kaaden [Kadaň] station, Fritz Ortlieb war photo album, 1916

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

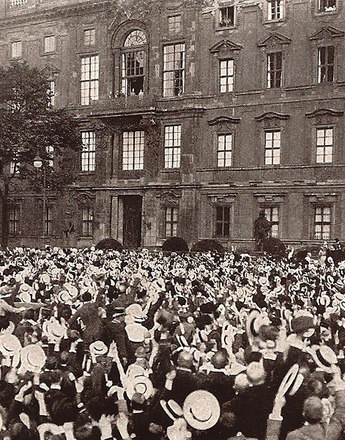

“Church service at the Bismarck Monument in Berlin on 2 August 1914”, photo

Copyright: Josef Neubauer

Immediately after the outbreak of the First World War, widespread sections of the Austrian-Hungarian population were gripped by nothing less than a war craze, scarcely conceivable from today’s perspective and knowing how many millions were killed through the war.

Enthusiasm for the war was evident not only in the Dual Monarchy but also in many other countries waging war. This mood reached a climax especially in Germany in late July and early August 1914. Public squares and streets were crowded with cheering people acclaiming the German Fatherland and demonstrating for the war. In the cities of the Habsburg Monarchy there were also frequent mass gatherings and patriotic demonstrations. Railway stations saw scenes of riotous celebration, manifest in newspaper pictures of the time. The recruits were hailed and sent off with flowers and tokens of affection. They went to war with confidence and certainty of victory, which – as was prophesied – would be theirs in any case within a few months.

Even Stefan Zweig, a writer who later spoke out in no uncertain terms against the war had to admit that "there was a majestic, rapturous and even seductive something in this first outbreak of the people from which one could escape only with difficulty. […] As never before, thousands and hundreds of thousands of people felt as they should have felt in peace time, that they belonged together […] each one experienced an intensification the self; he was no longer the isolated human being from earlier, he was integrated into the mass, he was the nation, and his person, his otherwise unnoticed person, had been given a meaning."

This is the feeling described by Stefan Zweig of a retrieved national unity; it describes the mood prevalent in July and for Germany the so-called "Augusterlebnis" (August experience). In the ecstasy of national exultation class distinctions seemed set aside and rivalling social classes united. "I know no more parties, I know only Germans" – thus the motto of the German Kaiser.

The war was deemed to be a means of overcoming the disintegration of society exacerbated by industrialisation and modernisation. With it, national and social tensions would retreat into the background and social distinctions abolished. The idea of national unity was of special significance most of all for the Habsburg Monarchy, for its stability had begun to totter owing to the enduring conflicts of nationalities. The author Hermann Bahr revealed his enthusiasm when he wrote: "The whole of Austria is one, of the same will, the same readiness, the same self-sacrifice, Germans, Slavs and Hungarians brothers, no more strife, harmony everywhere, Austria is here again! It seems a miracle. Whoever would have thought it?"

Nonetheless, this enthusiasm for the war was not a phenomenon that encompassed all sections of society, but one of many different sentiments to be found in the population in summer 1914. Propagandist and generalising versions of these sentiments deliberately camouflaged the ambivalent and negative voices at the outbreak of the war and thus hindered a more discriminating view.

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner: Der Erste Weltkrieg – Zeitenbruch und Kontinuität. Einleitende Bemerkungen, in: Dies. (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 15-41

Ferguson, Niall: Der falsche Krieg. Der Erste Weltkrieg und das 20. Jahrhundert, Stuttgart 1999

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2013

Sauermann, Eberhard: Literarische Kriegsfürsorge. Österreichische Dichter und Publizisten im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar, 2000

Steininger, Rolf: Einleitung: „Gott gebe, daß diese schwere Zeit bald ein Ende nimmt.“ Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2011, 7-25

Verhey, Jeffrey: Der Geist von 1914, in: Der Tod als Maschinist. Der industrialisierte Krieg 1914–1918. Eine Ausstellung des Museums Industriekultur Osnabrück im Rahmen des Jubiläums „350 Jahre Westfälischer Friede“ 17. Mai – 23. August 1998. Katalog, Bramsche 1998, 47-53

Winkelhofer, Martina: So erlebten wir den Ersten Weltkrieg. Familienschicksale 1914–1918. Eine illustrierte Geschichte, 2. Auflage, Wien 2013

Quotes:

"At last we welcomed with flowers ...": Mann, Golo: Deutsche Geschichte des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, Frankfurt am Main 1995, 589, quoted from: Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner: Der Erste Weltkrieg – Zeitenbruch und Kontinuität. Einleitende Bemerkungen, in: Dies. (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 16 (Translation)

"there was a majestic …": Zweig, Stefan: Die ersten Stunden des Krieges von 1914, in: ders.: Die Welt von Gestern. Erinnerungen eines Europäers, Frankfurt am Main 1970, 258, quoted from: Duiker, William J./Spielvogel, Jackson J.: World History. Volume II: Since 1500, Wadsworth 20137, 669

"I know no more parties …": Wilhelm II., quoted from: Verhey, Jeffrey: Der Geist von 1914, in: Der Tod als Maschinist. Der industrialisierte Krieg 1914–1918. Eine Ausstellung des Museums Industriekultur Osnabrück im Rahmen des Jubiläums „350 Jahre Westfälischer Friede“ 17. Mai – 23. August 1998. Katalog, Bramsche 1998, 49 (Translation)

"The whole of Austria is one …": Bahr, Hermann: Das österreichische Wunder, Stuttgart 1915, 5f., quoted from: Ernst, Petra/Haring, Sabine A./Suppanz, Werner: Der Erste Weltkrieg – Zeitenbruch und Kontinuität. Einleitende Bemerkungen, in: Dies. (Hrsg.): Aggression und Katharsis. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Diskurs der Moderne, Wien 2004, 18 (Translation)