The dialogue between the front line and the home front

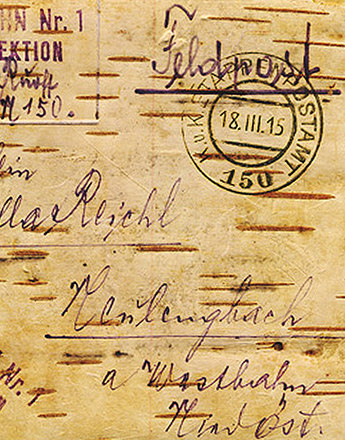

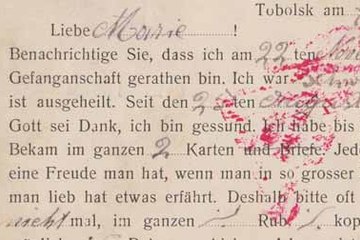

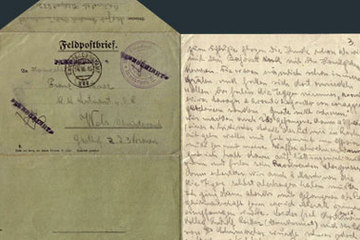

For the eight to nine million soldiers called up in the Habsburg Monarchy during the course of the First World War and their families, friends and acquaintances, the military postal system often provided the only form of contact. Receiving a sign of life in the shape of a letter or postcard was essential both for the soldiers at the front as well as their families at home.

Faced with constant uncertainty and strain, everybody wanted to know how their beloved son, brother, father or husband at the front was or, conversely, that the family at home were all well. Communication by letter also served as a substitute for daily conversation that could not be maintained when those concerned were separated. Thus many wartime letters also contain descriptions of banalities such as eating, sleeping or the weather, daily activities, news of children, siblings, friends and acquaintances. It was a way of letting one’s partner participate in one’s own daily life, of creating a connection with the familiar world of family and friends, a link with shared experiences from life as it had been before the war.

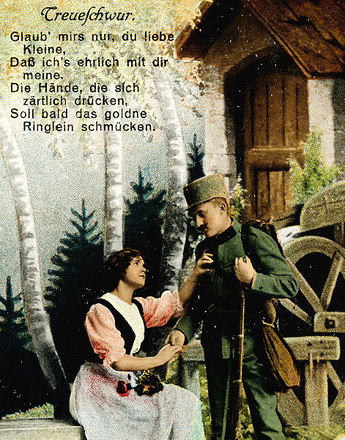

The majority of letters that have survived from this time contain not only descriptions of contemporary everyday life at home and on the front but also reminiscences of a shared past and hopes for a shared future. Since a shared present was mostly a thing of impossibility, memories of the past were frequently evoked as encouragement as well as to mitigate the strains of everyday wartime life and assuage the pangs of separation. Many correspondents regularly wrote about their plans for the future, imagining a life together in health and happiness with their relatives and friends after the war.

As the historian Ulrike Jureit has pointed out, the daily writing of letters served ‘to maintain the emotional bonds that were frequently threatened by the war’. Even the very act of writing expressed attentiveness and concern. In this way people attempted to preserve constellations of family and relationships, to express their feelings, give voice to their longings and to create a certain degree of intimacy. In addition to letters families also sent parcels to their loved ones at the front, typically containing warm clothing and homemade cakes and biscuits.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Hämmerle, Christa: Entzweite Beziehungen? Zur Feldpost der beiden Weltkriege aus frauen- und geschlechtergeschichtlicher Perspektive, in: Veit Didczuneit/Jens Ebert/Thomas Jander (Hrsg.): Schreiben im Krieg. Schreiben vom Krieg. Feldpost im Zeitalter der Weltkriege, Essen 2011, 241-252

Hämmerle, Christa: „… wirf Ihnen alles hin und schau, dass Du fortkommst.“ Die Feldpost eines Paares in der Geschlechter(un)ordnung des Ersten Weltkriegs, in: Historische Anthropologie (1998), 6/3, 431-458

Jureit, Ulrike: Zwischen Ehe und Männerbund. Emotionale und sexuelle Beziehungsmuster im Zweiten Weltkrieg, in: Werkstatt Geschichte (1999) 22, 61-73

Knoch, Peter (Hrsg.): Kriegsalltag. Die Rekonstruktion des Kriegsalltages als Aufgabe der historischen Forschung und Friedenserziehung, Stuttgart 1989

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: Liebe in Zeiten des Krieges. Die Feldpostkorrespondenz eines Wiener Ehepaares (1917/18), in: ÖGL (2012), 56/3, 231–246

Sturm, Margit: Lebenszeichen und Liebesbeweise aus dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Zur Bedeutung von Feldpost und Briefschreiben am Beispiel der Korrespondenz eines jungen Paares. Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Universität Wien 1992

Quotes:

„to maintain the emotional bonds ...“: Jureit, Ulrike: Zwischen Ehe und Männerbund. Emotionale und sexuelle Beziehungsmuster im Zweiten Weltkrieg, in: Werkstatt Geschichte (1999) 22, 62

-

Chapters

- Feldpost as an instrument of warfare

- How did a letter get from A to B?

- The dialogue between the front line and the home front

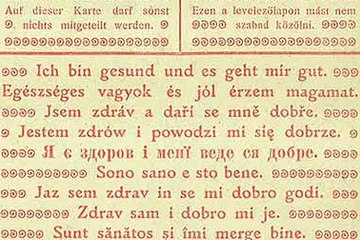

- ‘I am healthy and doing well.’

- The sending of ‘gifts of love’ to the front line and food parcels to the home front

- Instrumentalizing war correspondence to shape common perceptions of the war

- Women! Don’t write gloomy letters!