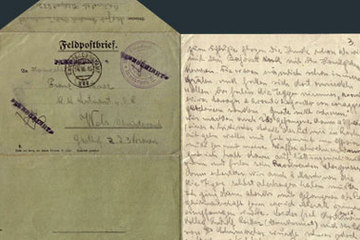

The sending of ‘gifts of love’ to the front line and food parcels to the home front

The sending of parcels from the home front to the front line was permitted from 10 August 1914, but had to be suspended for the first time by the beginning of September 1914 because the system was unable to cope with the volume of parcels being dispatched.

It was not until the end of 1916 that uninterrupted service for parcels could be guaranteed and was then maintained until the end of the war. The weight of these parcels was initially limited to a maximum of 5 kilos and a length of 60 cm. Owing to the huge demand in autumn 1914 this was increased to 10 kg and 80 cm, then reduced to the initial limits in December 1914. In addition to the sending of so-called Liebesgaben (‘gifts of love’), which were mostly organized by the state welfare office, the Red Cross or other charitable initiatives, the Warenprobenpaket (parcels of samples) were also enormously popular. These contained articles of everyday use such as ‘soap, combs, pocket-knives, smaller items of underwear, non-perishable foodstuffs and so on’, which the soldiers at the front found very useful.

In the opposite direction the sending of (private) parcels from the front line to the home front ‘was not permitted during the first years of the war for ‘sanitary’ reasons’. Exceptions were made in individual cases and at particular times of year, such as spring or autumn, when soldiers at the front were able to send home winter or summer clothing that they no longer needed.

It was not until 1917 that the sending of (private) parcels from the front to the home front was allowed on a larger scale. With the deterioration in the supply of foodstuffs and other goods in the Monarchy soldiers now began to send home food, everyday articles and raw materials. Thus during the nineteen-month occupation of Romania by Austro-Hungarian troops around 3,856,000 parcels were sent to the home front, and after the invasion of the Ukraine in the spring of 1918 similar if not greater numbers of food parcels were sent back to the homeland.

The brisk traffic in parcels from the front line to the homeland – via the military postal system or sent back with fellow-soldiers on home leave – played a significant role in supplying families with food and commodities.

At the same time the sending of parcels by soldiers and officers represented a huge burden for the civilian population in the occupied territories, as foodstuffs, commodities and raw materials were frequently requisitioned according to the provisions of the Kriegsleistungsgesetz (War Requirements Act), that is, confiscated and commandeered.

In addition to requisitioning there were frequent occurrences of theft and plundering, which was forbidden by martial law. As the historians Oswald Überegger and Matthias Rettenwander have documented in the case of Tyrol during the First World War, soldiers and officers in the Austro-Hungarian Army also went on targeted and planned ‘shopping trips’ to local farmers, where they ignored the officially permitted market prices for foodstuffs, paying more than the civilian population could afford. In doing so they not only continually forced up prices to the detriment of the local population but also stoked the already flourishing black market.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 1964

Hämmerle, Christa: „Habt Dank, Ihr Wiener Mägdelein …“ Soldaten und weibliche Liebesgaben im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: L’Homme. Zeitschrift für Feministische Geschichtswissenschaft (1997) 8, 132-154

Höger, Paul: Das Post- und Telegraphenwesen im Weltkrieg, in: Gatterer, Joachim/Lukan, Walter (Red.): Studien und Dokumente zur österreichisch-ungarischen Feldpost im Ersten Weltkrieg, Bd. 1, Wien 1989, 23-54

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: „Wenn wir nur glücklich wieder beisammen wären …“ Der Krieg, der Frieden und die Liebe am Beispiel der Feldpostkorrespondenz von Mathilde und Ottokar Hanzel (1917/18), Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Wien 2010

Überegger, Oswald/Rettenwander, Matthias: Leben im Krieg. Die Tiroler Heimatfront im Ersten Weltkrieg, Bozen 2004

Quotes:

„The weight of these parcels …“: figures, quoted from: Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 1964, 504

„soap, combs, pocket-knives ...“: quoted from: Höger, Paul: Das Post- und Telegraphenwesen im Weltkrieg, in: Gatterer, Joachim/Lukan, Walter (Red.): Studien und Dokumente zur österreichisch-ungarischen Feldpost im Ersten Weltkrieg, Bd. 1, Wien 1989, 45

„for sanitary reasons“: Clement, Alfred (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Feld- und Militärpost II. 1914-1918, Graz 196, 504

„[…] during the nineteen-month occupation …“: figures, quoted from: Höger, Paul: Das Post- und Telegraphenwesen im Weltkrieg, in: Gatterer, Joachim/Lukan, Walter (Red.): Studien und Dokumente zur österreichisch-ungarischen Feldpost im Ersten Weltkrieg, Bd. 1, Wien 1989, 46

„soldiers and officers (...) went on targeted and planned ...“: Überegger, Oswald/Rettenwander, Matthias: Leben im Krieg. Die Tiroler Heimatfront im Ersten Weltkrieg, Bozen 2004, 171

-

Chapters

- Feldpost as an instrument of warfare

- How did a letter get from A to B?

- The dialogue between the front line and the home front

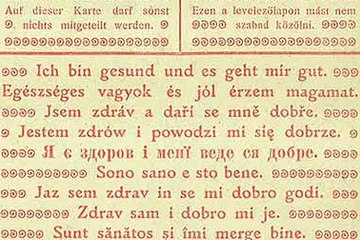

- ‘I am healthy and doing well.’

- The sending of ‘gifts of love’ to the front line and food parcels to the home front

- Instrumentalizing war correspondence to shape common perceptions of the war

- Women! Don’t write gloomy letters!