Instrumentalizing war correspondence to shape common perceptions of the war

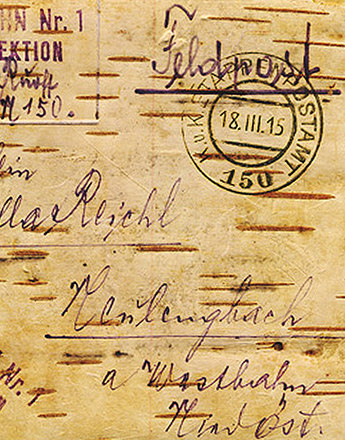

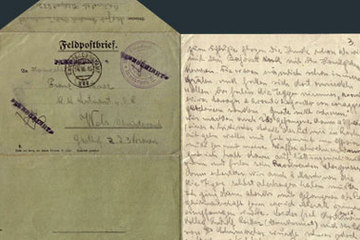

In everyday wartime life, which was dominated by propaganda and censorship, letters from the front assumed a special status. The ‘immediate proximity of its writers to the events of the war at the front’ gave it an otherwise almost unachievable ‘authenticity’.

According to the historian Bernd Ulrich, the letter sent from the front became the ‘medium of the eye-witness’, who in contrast to fictional accounts and other writing on the war promised to convey an ‘undistorted’ view of events at the front as well as the day-to-day life of the ordinary private.

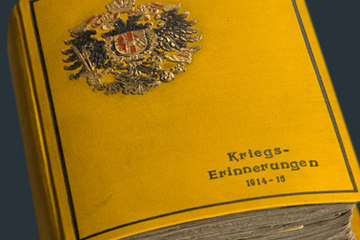

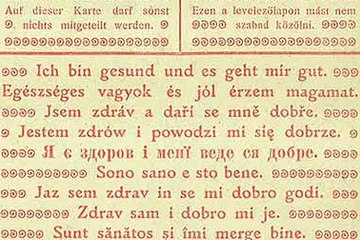

This perspective was also encouraged by the regular publication of selected letters from the front in the Austro-Hungarian press, an activity that started shortly after the beginning of the war. Thus ‘the Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung (then as now a highly popular publication) established a permanent column with the title Aus unserer Feldpostmappe (‘From our Feldpost file’)’, and regional dailies such as the Eggenburger Zeitung. Illustriertes Wochenblatt contained a regular section called Soldaten- und Feldbriefe (‘Letters from soldiers in the field’). In addition a number of collections of letters from the front were published, some rather hastily put together. All these publications only reflected voices that were patriotic, keen to fight and provided allegedly ‘authentic’ accounts from the field. This public ‘orchestration’ – Bernd Ulrich even speaks of the ‘domination of the Feldpost letter’ – quickly came to shape how the war was represented and interpreted.

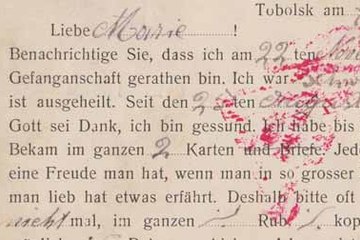

At the beginning of the conflict enthusiasm for the war was often expressed in private correspondence, and some of the writers expected that it would be of brief duration and result in victory for the Monarchy. However, relatively soon these voices took on a different note, and critical opinions became more frequent. Complaints about how long the war was lasting could be heard, as well as grievances about the deteriorating supply situation at the front and in the towns and cities at home. Letters reflected incessant worry about loved ones, the long periods of separation and the constant presence of death, suffering and privation, in crass contrast to what the authorities wished people to write about.

As the war went on the military authorities attempted to influence both the form and content of letters sent to and from the front via the daily press and other publications, issuing instructions on the correct way to write them. As the historian Martin Humburg has discovered in his research on the Second World War, the Feldpost letter increasingly came to assume the significance of a ‘weapon’ that could have a positive or negative influence on the soldiers’ fighting morale and thus on the course of the war. In this context, the findings of his research can also be applied to the First World War, when it was seen as the duty particularly of women to write only of pleasurable and edifying things from everyday life on the home front. This was intended to bolster the will to fight and the determination to ‘hold out’ at the front.

Translation: Sophie Kidd

Humburg, Martin: Das Gesicht des Krieges. Feldpostbriefe von Wehrmachtssoldaten aus der Sowjetunion 1941-1944, Wiesbaden 1998

Humburg, Martin: Deutsche Feldpostbriefe im Zweiten Weltkrieg – Eine Bestandsaufnahme, in: Vogel, Detlef/Wette, Wolfram (Hrsg.), Andere Helme – andere Menschen? Heimaterfahrung und Frontalltag im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Ein internationaler Vergleich (Tübingen 1995), 13-35

Rebhan-Glück, Ines: Liebe in Zeiten des Krieges. Die Feldpostkorrespondenz eines Wiener Ehepaares (1917/18), in: ÖGL (2012), 56/3, 231–246

Spann, Gustav: Vom Leben im Kriege. Die Erkundung der Lebensverhältnisse der Bevölkerung Ungarns im Ersten Weltkrieg durch die Briefzensur, in: Ardelt, Rudolf G. Ardelt/Huber, Wolfgang J.A./u.a. (Hrsg.): Unterdrückung und Emanzipation. Festschrift für Erika Weinzierl zum 60. Geburtstag, Wien 1985, 149-165

Sturm, Margit: Lebenszeichen und Liebesbeweise aus dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Zur Bedeutung von Feldpost und Briefschreiben am Beispiel der Korrespondenz eines jungen Paares. Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Universität Wien 1992

Ulrich, Bernd: Die Augenzeugen. Deutsche Feldpostbriefe in Kriegs- und Nachkriegszeit 1914-1933, Essen 1997

Ulrich, Bernd: Militärgeschichte von unten.“ Anmerkungen zu ihren Ursprüngen, Quellen und Perspektiven im 20. Jahrhundert, in: Geschichte und Gesellschaft (1996), 22, 473-503

Quotes:

„immediate proximity of its writers ...“: Ulrich, Bernd: Die Augenzeugen. Deutsche Feldpostbriefe in Kriegs- und Nachkriegszeit 1914-1933, Essen 1997, 12-13

„medium of the eye-witness“: Ulrich, Bernd: Die Augenzeugen. Deutsche Feldpostbriefe in Kriegs- und Nachkriegszeit 1914-1933, Essen 1997, 11

„Thus the Illustrierte Kronen Zeitung ...“: Sturm, Margit: Lebenszeichen und Liebesbeweise aus dem Ersten Weltkrieg. Zur Bedeutung von Feldpost und Briefschreiben am Beispiel der Korrespondenz eines jungen Paares. Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Universität Wien 1992, 35

„domination of the Feldpost letter“: Ulrich, Bernd: Die Augenzeugen. Deutsche Feldpostbriefe in Kriegs- und Nachkriegszeit 1914-1933, Essen 1997, 36

„[…] the significance of a weapon ...“: Humburg, Martin: Das Gesicht des Krieges. Feldpostbriefe von Wehrmachtssoldaten aus der Sowjetunion 1941-1944, Wiesbaden 1998, 16

-

Chapters

- Feldpost as an instrument of warfare

- How did a letter get from A to B?

- The dialogue between the front line and the home front

- ‘I am healthy and doing well.’

- The sending of ‘gifts of love’ to the front line and food parcels to the home front

- Instrumentalizing war correspondence to shape common perceptions of the war

- Women! Don’t write gloomy letters!