‘Everyday life’ without combat – ‘everyday life’ despite combat

Field mass, photo, 1916

Copyright: private Leihgeberin

-

“Field mass”, photograph, undated

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

“Christmas 1917”, extract from Fritz Ortlieb's war photo album

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

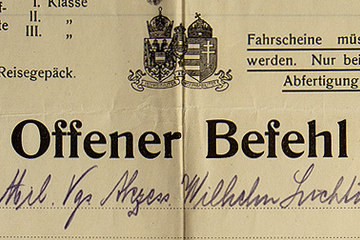

“Open order” by an officer of the Austro-Hungarian mountain bakery no. 108, 1918

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

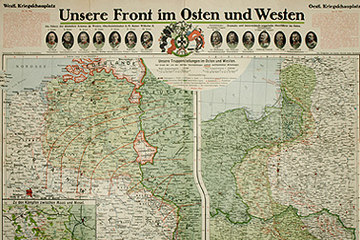

‘Everyday life’ on the front was structured into variously intensive intervals of time. There were periods marked by extremely strenuous activity and high-risk potential, but also times when the soldiers could experience “relative peace and quiet, and [even] relax.”

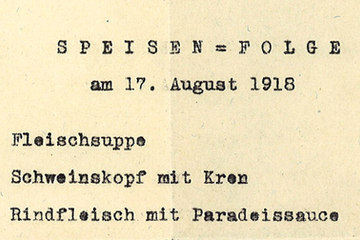

In the so-called “Etappe” – station HQ – soldiers were meant primarily to recover from the stress of action on the front, take it easy, and regain their “fighting spirit”. ‘Diversions” and leisure activities took the form of trips to nearby townships and villages, visiting cafés and so forth. Not seldom, these trips were marked by an extensive consumption of alcohol. Besides which, the soldiers – wherever available – had the opportunity of going to the front theatre or front cinema and also a brothel. Specially set-up soldier homes, writes Isabelle Brandauer, “separated according to religion”, offered the opportunity of reading newspapers and books or playing cards. Another activity available to front soldiers in the “Etappe” was to read and write cards and letters for the military postal service; millions of letters and cards were despatched to their relatives at home, and vice versa.

The combat-free ‘everyday life’ of the soldier was not complete without military drill, which took the form of constantly necessary building activities in the trenches and positions, also training sessions and further education. These included courses teaching the soldiers to handle mine-throwing, hand grenades and gas masks, or skiing and climbing courses for those deployed on the Southwestern Front.

Religious feast days and the birth- and name day of the emperor were also events offering a welcome change in everyday life on the front for the soldiers. As Christa Hämmerle has shown, it was particularly the Catholic soldiers – 75 to 80 percent in comparison with their Protestant, Jewish, Muslim and Serbian-Orthodox comrades – who not only represented the largest denominational group “but had most rights or options for practising their religion, regardless of the constitutionally anchored prerogative of equality.”

Religion certainly played an important role in giving a meaning to life and an interpretative framework for many soldiers. But at the same time religious doubt and mental crises could be observed in the soldiers, as demonstrated by research, for instance by Benjamin Ziemann and Matthias Rettenwander.

In principle, there was an endeavour to celebrate religious services not only on feast days, but also hold regular Masses in the field. The Catholic field chaplain administered the sacraments, buried the dead and provided the soldiers with suitable literature. The same applied to the field rabbis deployed during the war, of whom according to Erwin Schmidl, there were “no fewer than 76 (…) in the Imperial-Royal Army in 1918”.

An event constantly uppermost in the soldiers’ minds, expectations and longings was home leave. It offered a welcome opportunity of escaping from life on the front for a while and of seeing wife, fiancée, girlfriend, children, parents and siblings again, who were not allowed to visit the positions. Applications for leave were accordingly very numerous, but irregularly issued – a practice the soldiers felt to be unjust. This applied as well to applications for home leave in order to help with the harvest, or because of a death in the family. In addition there were bans on taking leave prior to major troop mobilisations or offensives. It occurred quite often that soldiers were on front duty for more than a year. The discrepancies in granting leave to the ranks and even more in relation to superior officers had a great influence on the troopers’ mood, which was frequently marked by rage and hatred against the comrades who got ‘preferential treatment’.

If leave was finally given, the soldier’s relief and delight was accordingly unbounded and he could depart with his certificate of leave. He had to keep this carefully and show it on demand. In contrast, “for persons of the army in the field,” writes Isabelle Brandauer “the ‘basic command’ sufficed as a travel certificate.”

Translation: Abigail Prohaska

Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007

Hämmerle, Christa: Soldaten, in: Labanca, Nicola/Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Krieg in den Alpen. Österreich-Ungarn und Italien im Krieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2014, im Druck

Rettenwander, Matthias: Der Krieg als Seelsorge. Katholische Kirche und Volksfrömmigkeit in Tirol im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2006

Schmidl, Erwin A.: Juden in der k.(u.)k. Armee 1788–1918, Eisenstadt 1989

Ziemann, Benjamin: Front und Heimat. Ländliche Kriegserfahrungen im südlichen Bayern 1914–1923, Essen 1997

Quotes:

„relative peace and quiet ...“: quoted from: Ziemann, Benjamin: Front und Heimat. Ländliche Kriegserfahrungen im südlichen Bayern 1914–1923, Essen 1997, 76

„separated according to religion“ : quoted from: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 83

„These included courses …“: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 87-90

„but had most rights ...“: quoted from: Hämmerle, Christa: Soldaten, in: Labanca, Nicola/Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Krieg in den Alpen. Österreich-Ungarn und Italien im Krieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2014, in the press

„no fewer than 76 …“: quoted from: Schmidl, Erwin A.: Juden in der k. (u.) k. Armee 1788–1918, Eisenstadt 1989, 80

„for persons of the army ...“: quoted from: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007, 104

„But at the same time religious doubt …“: literature reference for: Ziemann, Benjamin: Front und Heimat. Ländliche Kriegserfahrungen im südlichen Bayern 1914–1923, Essen 1997, insbes. 246–265; Rettenwander, Matthias: Der Krieg als Seelsorge. Katholische Kirche und Volksfrömmigkeit in Tirol im Ersten Weltkrieg, Innsbruck 2006.