-

“Battery on the march to Zalošče”, Slovenian theatre of war, photograph, 1915, extract from Leopold Wolf's war photo album

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

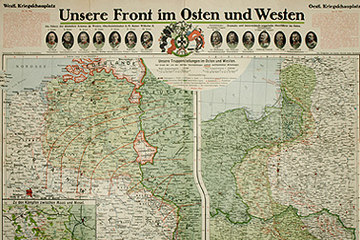

The First World War lasted four long years; it was not only a long war but it was also fought in very different theatres. For many soldiers of the Monarchy this meant moving around in unfamiliar lands and coming into contact with the resident population.

Diaries and forces post thus contain detailed descriptions of landscapes, buildings and villages, descriptions of local customs and mores, also stories about the local population, not seldom peppered with prejudiced and racially charged comments.

But even more than ‘foreignness’, the troops of the Monarchy had to come to terms with the climate, the weather conditions, extremes of snow and avalanches, ice and thaw, the blast of gales and prolonged rainfalls, also unbearable heat waves. An officer of the 58th Infantry Regiment described the retreat from the San Line in November 1914 with the following words: “Autumn cold slicing through us. Sleet. Muddy paths, trodden by thousands of soldiers’ boots, rutted by cartwheels and artillery teams. March with full baggage. Dysentery is rife. The nights are spent in the open field or in barns and sheds, the wind whistling through. Intolerable fatigue – rest in wet ditches along the way, where we fell asleep on the spot. Food at night, presuming the field kitchen made it to the company. And finally the worst of the scourges to plague the soldier – lice, lice and more lice […]. There was neither time nor place to destroy them.”

The exertions of these retreats were exacerbated not only by the weather conditions, but also – and this particularly affected the infantry – by the loads that had to be carried for days. These included bayonet, coat, blanket, tent equipment, underwear, cartridges, steel helmet (first introduced in 1916), emergency rations and much more, all weighing around 20 kg. The weight might be increased a further five to six kilos, Isabelle Brandauer tells us, if you count the gun and strap, or an extra load added in winter consisting of woollen gloves, puttees, knitted vests and underpants and various field utensils – cooking pots, bucket, spades, a lantern and so on.

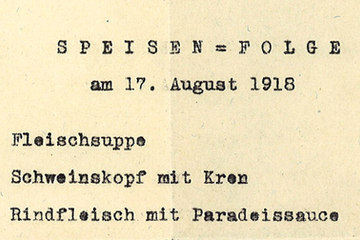

The inadequate winter equipment and clothing, sleeping outside, the lack of water supply and provisions from the field kitchens lagging behind the army led very early on to the first experiences of hunger and effects of shortages, also diseases such as dysentery. It spread relatively soon after the outbreak of the war in Serbia, Bosnia, South Hungary, Galicia and Russia. Systematic immunisation of the troops, as Elisabeth Dietrich pointed out, was only introduced in 1915, the second year of the war. By then around 120,000 soldiers had contracted dysentery, another 5,000 had died by then.

Translation. Abigail Prohaska

Biwald, Brigitte: Von Helden und Krüppeln. Das österreichisch-ungarische Militärsanitätswesen im Ersten Weltkrieg, Teil 2, Wien 2002

Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg 1915–1917, Innsbruck 2007

Dietrich, Elisabeth: Der andere Tod. Seuchen, Volkskrankheiten, und Gesundheitswesen im ersten Weltkrieg, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck/Wien 1995, 255–275

Hämmerle, Christa: Soldaten, in: Labanca, Nicola/Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Krieg in den Alpen. Österreich-Ungarn und Italien im Krieg, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2014, im Druck

Szlanta, Piotr: Unter dem sinkenden Stern der Habsburger. Die Ostfronterfahrung polnischer k.u.k. Soldaten, in: Bachinger, Bernhard/Dornik, Wolfram (Hrsg.): Jenseits des Schützengrabens. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Osten: Erfahrungen – Wahrnehmungen – Kontext, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2013, 139–156

Quotes:

„Autumn cold slicing through us ...“: Stanisław Sosabowski, quoted from: Zlanta, Piotr: Unter dem sinkenden Stern der Habsburger. Die Ostfronterfahrung polnischer k. u. k. Soldaten, in: Bachinger, Bernhard/Dornik, Wolfram (Hrsg.): Jenseits des Schützengrabens. Der Erste Weltkrieg im Osten: Erfahrungen – Wahrnehmungen – Kontext, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2013, 147

„The weight might be increased a further …“: Brandauer, Isabelle: Menschenmaterial Soldat. Alltagsleben an der Dolomitenfront im Ersten Weltkrieg, 1915 – 1917, Innsbruck 2007, 126

„By then around 120,000 soldiers had …“: figures quoted from: Dietrich, Elisabeth: Der andere Tod. Seuchen, Volkskrankheiten, und Gesundheitswesen im ersten Weltkrieg, in: Eisterer, Klaus/Steininger, Rolf (Hrsg.): Tirol und der Erste Weltkrieg, Innsbruck/Wien 1995, 258