The "Eastern Jews" as a pivotal point for anti-Jewish agitation

When in winter 1915 over 130,000 persons sought refuge in Vienna from the Tsarist army, the initial reaction was one of sympathy. However, the mood rapidly swung against the mostly Jewish migrants from the Galician "shtetls", and anti-Semites began to prepare their weapons.

During the war, the Jewish civil population suffered from the effects of the armed conflict in the same way as the non-Jewish population, and many Jews supported the activities on the home front. They became involved in patriotic and welfare organisations, subscribed war loans and supported the roughly 300,000 Jewish soldiers and their families.

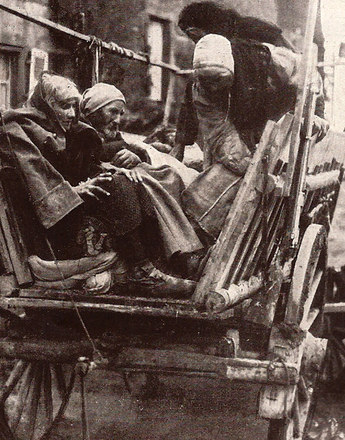

However, the precarious situation of the Jewish population in Vienna deteriorated when shortly after the start of the war the largest movement of Jewish refugees since the 17th century began. The defeats in the first months of the war and the Tsarist army's invasion of Galicia and the Bukovina caused thousands of families within the Empire to flee – for many a traumatic event. Flight was rarely carefully prepared and only few succeeded in rescuing their mostly meagre possessions.

It is not possible to put a definite number on the Jewish refugees. According to estimates, in the first phase of the war roughly 400,000 Jews from the eastern part of the Empire were forced to flee. For many, the destination was Vienna, where they hoped to find help from family members and acquaintances. In autumn 1915, the Austrian Ministry of the Interior estimated the number of refugees in Vienna at 137,000, the majority of whom were Jewish, which led to a considerable increase in the size of the Jewish population.

Accommodating, feeding and ensuring the daily survival of the refugees from Galicia and the Bukovina was an almost insoluble challenge to the authorities. Most of the displaced persons came from regions where Jews constituted a high percentage of the population, where their lives were characterised by poverty and a commitment to religious traditions. Numerous associations and private individuals, including many women in particular, provided assistance to the Jewish refugees, opening soup kitchens and field hospitals and organising childcare facilities and accommodation for the new arrivals.

Within the Jewish community, there was disagreement as to how the refugees should be treated, long-established Jews fearing that the presence of the impoverished "Eastern Jews" would stir up anti-Semitism even further. And indeed, the large number of Jewish arrivals triggered a defensive reaction amongst the Viennese population, and the mood swung to an opposition to the refugees from the east.

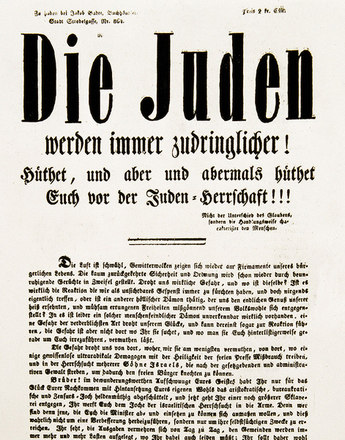

This rejection fed on the fear of "the alien" and on the anti-Semitic resentment that had been handed down for centuries. In addition, the shortage of food, heating material and accommodation worsened, a precarious situation that was exploited by anti-Semitic agitators. Although the number of Jewish refugees in Vienna never exceeded 125,000, and by 1921 all but 26,000 Jewish migrants had been returned to where they came from, the impoverished refugees became the central motif of anti-Semitic agitation. In the strongest terms possible, Jews were made responsible for the raging social problems and attacked with defamatory accusations such as "eastern Jews", "hoarders", "speculators" and "war profiteers".

This swing in the mood was also reflected in the mood reports filed by the Vienna police. On 1 October 1914, under the heading "Galician refugees", a report read: "The population of the second district, where they [Galician refugees] are mostly to be found, is already beginning to see them as a very unpleasant invasion and, in addition to the already perceptible rise in the cost of food, there is a fear that disease might spread."

However, anti-Semitic agitation did not reach its peak until after the end of the war, when the political parties made the issue part of their political programmes.

Translation: David Wright

Hoffmann-Holter, Beatrix: „Abreisendmachung“. Jüdische Kriegsflüchtlinge in Wien 1914 bis 1923, Wien et al. 1995

Lichtblau, Albert: Integration, Vernichtungsversuche und Neubeginn – Österreichisch-jüdische Geschichte 1848 bis zur Gegenwart, in: Brugger, Eveline et al. (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Juden in Österreich, Wien 2006, 447-566

Lichtblau, Albert: Zufluchtsort Wien. Jüdische Flüchtlinge aus Galizien und der Bukowina, in: Patka, Markus im Auftrag des jüdischen Museums Wien (Hrsg.): Weltuntergang. Jüdisches Leben und Sterben im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien/Graz/Klagenfurt 2014, 134-142

Rechter, David: The Jews of Vienna and the First World War, London 2001

Quotes:

„„Die Bevölkerung des zweiten Bezirks...“: Stimmungsberichte aus der Kriegszeit, k. k. Polizeidirektion Wien, 1. Oktober 1914, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus

-

Chapters

- Antisemitism: A historical definition

- Jewish life in the Habsburg Empire

- Anti-liberalism – anti-capitalism – anti-Semitism

- Antisemitism as a political movement

- "I decide who is a Jew"

- The social exponents of Austrian anti-Semitism

- Anti-Semitism in other nationalities within the Habsburg Monarchy

- The Habsburg Monarchy as the guarantee of pluralistic identities

- Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army

- The "Eastern Jews" as a pivotal point for anti-Jewish agitation

- The breakdown of the internal peace