The War Monitoring Office and press censorship

By instruction of 27 July 1914, a War Monitoring Office (WMO) was set up in the Ministry of War in Vienna under the direction of Leopold von Schleyer as the top-level authority for ensuring the enforcement of the emergency regulations.

In Hungary, an organisation corresponding to the WMO was set up, the War Monitoring Commission, based in Budapest. An officer of the Hungarian Ministry of National Defence "was appointed ‘liaison officer’” in order to facilitate the collaboration between the two organisations and to coordinate the measures and regulations in the two halves of the Empire.

As “supervisory and executive authority”, the War Monitoring Office was in particular intended to take measures against espionage and activities directed against the state and the armed forces, and to act as contact point for information about inadequacies in the emergency regulations. Its jurisdiction covered “the entire territory of the kingdoms and countries represented in the Reichsrat and Bosnia-Herzegovina”.

The WMO's five action groups also included a Censorship Group, which in turn was broken down into press censorship (political and military press), letter censorship and telegram censorship.

Political censorship of the press was the function of staff from various ministries, while the military press was the responsibility of members of the armed forces, mainly officers. The censorship of telegrams was organised entirely in military form, while with letters the representatives of the Imperial-Royal Ministry for Trade, Finance and Justice worked together with the armed forces.

One of the main fields of activity of the WMO was to monitor printed publications, regulated in Sec. 7 of Service Manual J-25 a. Thus, as a result of the suspension of freedom of the press, newspaper publishers were required to submit statutory copies of their media products to the WMO for assessment within a specific deadline. In general, reports on military news were only permitted if they had previously been released by the War Press Headquarters (WPH) or the Press Office of the Minister of War.

From December 1915, press conferences were held daily in the rooms of the WMO between 5.30 and 6.30 in the evening, at which representatives of the ministries and journalists received instructions as to how they should handle the political events of the day. Journalists were allowed to put questions to and discuss with the WMO's representatives.

In the course of 1917, “wartime absolutism” was increasingly watered down by Emperor Karl and his Foreign Minister Graz Czernin, reflected inter-alia in the reconvening of the Reichsrat in May 1917. The War Monitoring Office and its activities were increasingly subject to public criticism. In August 1917, therefore, the head of the Office was dismissed and preparations were made to establish a more ‘legitimate’ successor organisation, the Ministerial Commission in the Ministry of War. Despite the change in the administrative structure and lines of communication, the Ministerial Commission, however, continued the work of the War Monitoring Office “practically without interruption”.

Translation: David Wright

Ehrenpreis, Petronilla: Kriegs- und Friedensziele im Diskurs. Regierung und deutschsprachige Öffentlichkeit Österreich-Ungarns während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2005

Scheer, Tamara: Das Kriegsüberwachungsamt: von den Anfängen bis zum Ausbruch des Weltkriegs 1914, Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Universität Wien 2004

Scheer, Tamara: Kontrolle, Leitung und Überwachung des Ausnahmezustandes während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 2006

Schwendinger, Christian: Kriegspropaganda in der Habsburgermonarchie zur Zeit des Ersten Weltkriegs. Eine Analyse anhand fünf ausgewählter Zeitungen, Hamburg 2011, 57-58

Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972

Quotes:

„was appointed ...“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 57

„supervisory and executive authority“: quoted from: Ehrenpreis, Petronilla: Kriegs- und Friedensziele im Diskurs. Regierung und deutschsprachige Öffentlichkeit Österreich-Ungarns während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2005, 68

„the entire territory of the kingdoms ...“: quoted from: Ehrenpreis, Petronilla: Kriegs- und Friedensziele im Diskurs. Regierung und deutschsprachige Öffentlichkeit Österreich-Ungarns während des Ersten Weltkriegs, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2005, 69

„One of the main fields ...": Scheer, Tamara: Das Kriegsüberwachungsamt: von den Anfängen bis zum Ausbruch des Weltkriegs 1914, Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Universität Wien 2004, 104-106

„From December 1915 …“: Scheer, Tamara: Das Kriegsüberwachungsamt: von den Anfängen bis zum Ausbruch des Weltkriegs 1914, Unveröffentlichte Diplomarbeit, Universität Wien 2004, 117

„practically without interruption“: quoted from: Spann, Gustav: Zensur in Österreich während des Ersten Weltkrieges 1914-1918, Unveröffentlichte Dissertation, Universität Wien 1972, 60

-

Chapters

- "Wartime absolutism" – and the revocation of civic rights

- The War Monitoring Office and press censorship

- Blank spaces, everywhere!

- Everything is censored!

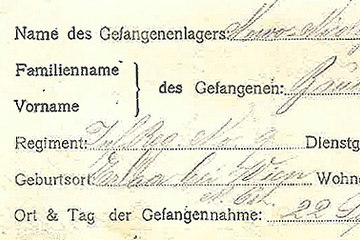

- Monitoring of the post – letter censorship

- Censorship with ink and scissors and seeking for information material

- “Hypercensorship” and mood reports

- Circumventing the censorship and "self-censorship"