-

Weight table of Maria Lienhart, entries for years 1914 to 1921

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

Postcard from Attnang of 15 July 1919, address side

Copyright: Herta Rohringer

In 1916 the hunger disaster spread unstoppably throughout the Habsburg Monarchy. In their affliction women became the harshest critics of the state, demanding an end to the war.

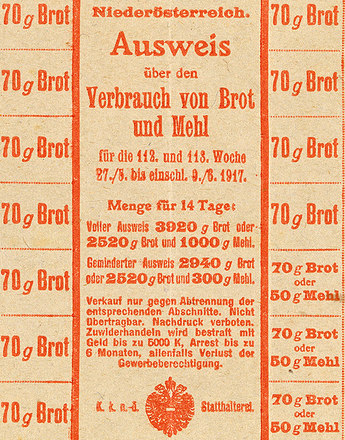

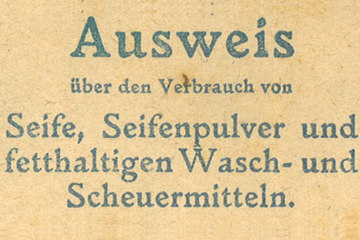

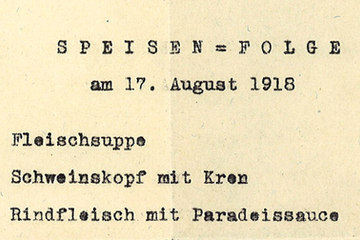

In the last two years of the war, a change of thinking came about. Everyday life was marked by nightlong queuing for ever shrinking amounts of basic food, repeated shortages in rations allocated, conflicts between police, traders and customers, half-starved children and women marked by malnourishment. In view of the poor supply situation, tubercular diseases rose rapidly; pneumona, hunger swelling, influenza and dysentery claimed their first victims. The number of deaths by many times in the civilian population and the psychological strains led to aggression and hostility in people’s dealings with one another.

In Vienna in May 1916 the first food disturbances occurred. Groups of emaciated youths plundered food wagons and smashed in shop windows, women formed into protest chains and marched towards the central district to declare their anger. The police reacted with a wave of arrests and imposed a curfew on the city. The censor still ensured that nothing was to be read of these first hunger riots in the newspapers. Yet the state power kept a close eye on these armies of queuing people, fearing after all that they could form into protest and revolt movements.

In fact the fury of the population over the sinking food rations was articulated in the coming years into a series a spontaneous riots and demonstrations. On May 18, 1916 the Austro-Hungarian police directorate noted: ‘The excited mood of the population resulted on the 11 of the month in clashes (hunger riots) at the market at Eugenplatz in the X. Distr. [sic!] which spread to the districts of Rudolfsheim and Schmelz in the following days. Bitter massed assemblies also took place at markets of other districts […]. The demonstrators tended to yell out such slogans as “We are hungry, we have to be hungry with our children, give us something to eat, down with the price drivers, we want peace”etc.’.

These hunger protests were mostly held by women, who thus won influence over ‘high politics’. When the flour allocation were restricted yet again in January 1918, strikes broke out in almost every region of the monarchy. Social democracy positioned itself at the head of the strike and articulated both economic and political demands. The strikes continued throughout 1918, with protests against price increases, poor working conditions and the miserable food supply situation.

In early summer of 1918 social tensions between city and countryside reached a climax. At the end of June when the bread rations were to be reduced by half once again, the patience of the city dwellers ran out. Stoked by rumours of food held back and by the unscrupulous lack market prices, thousands of Viennese marched into surroundings towns and villages. There the women, children and soldiers plundered the fields, forced the farmers to hand out food, and threatened them with violence. The conflicts continued until July 1918. The resilience of the civilian population had reached its limit and wide swathes of the population were no longer prepared to bear the burden of this war.

Augeneder, Sigrid: Arbeiterinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen proletarischer Frauen in Österreich, Wien 1987

Bauer, Ingrid: Frauen im Krieg. Patriotismus, Hunger, Protest – weibliche Lebenszusammenhänge zwischen 1914 und 1918, in: Mazohl-Wallnig, Brigitte (Hg.): Die andere Geschichte 1. Eine Salzburger Frauengeschichte von der ersten Mädchenschule (1695) bis zum Frauenwahlrecht (1918), 285-310

Hautmann, Hans: Hunger ist ein schlechter Koch. Die Ernährungslage der österreichischen Arbeiter im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Botz, Gerhard et al. (Hrsg.): Bewegung und Klasse. Studien zur österreichischen Arbeitergeschichte. 10 Jahre Ludwig Boltzmann Institut für Geschichte der Arbeiterbewegung, Wien/München/Zürich, 1978, 661-682

Healy, Maureen: Vienna and the Fall of the Habsburg Empire. Total War and Everyday Life in World War I, Cambridge 2004

Pfoser, Alfred: Wohin der Krieg führt. Eine Chronologie des Zusammenbruchs, in: : Pfoser, Alfred/Weigl, Andreas (Hrsg.): Im Epizentrum des Zusammenbruchs. Wien im Ersten Weltkrieg. Wien 2013, 580-688

Quotes:

„Die erregte Stimmung der Bevölkerung...“: Stimmungsberichte aus der Kriegszeit, k. k. Polizeidirektion Wien, 18. Mai 1916, Wienbibliothek im Rathaus