The war after the war – reflection, homecoming and review

The topics writers dealt with were many and varied. They ranged from enthusiasm for the war and wartime propaganda to descriptions of battles with individual experiences and feelings. The types of text that were used were just as varied – including diary entries, essays, poems, dramas and novels.

The descriptions came from authors who fought at the front and from authors who remained behind the lines. Some were written immediately while the war was in progress, others only after the war, the latter in many cases a way of mentally processing what was actually beyond comprehension. This is how the First World War became the topic that dominated literature after 1918. Ernst Jünger’s book In Stahlgewittern (In Storms of Steel) is based on diary entries he made on the western front between 1915 and 1918 and then published in various versions from 1920 on. Jünger depicted the war as a natural phenomenon governed by fate; he did not judge and he did not recognisably express an opinion either. But what he remembered was reading Karl May, and he described himself as an adventurous Old Shatterhand at the front: ‘My fourth-form memories of Karl May came back to me as I was sliding on my belly through the grass wet with dew and the undergrowth of thistles … ‘Heiner Müller has commented: ‘Jünger’s problem is a problem of the twentieth century, namely that for him the experience of war came before the experience of women.’

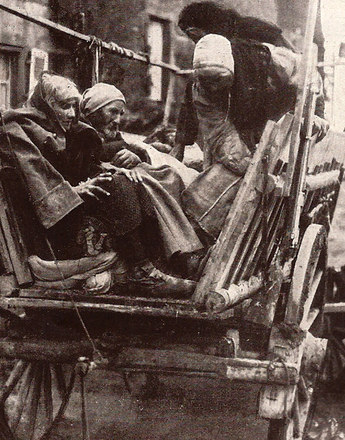

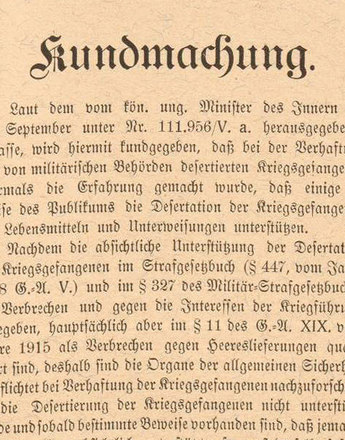

Escape, desertion and the motives for them and their consequences are themes frequently found in the literature of the war. Thus Stefan Zweig’s short story Episode am Genfer See (Episode on Lake Geneva) from 1926 tells the story of the Russian soldier Boris, who after a bullet wound flees from the sick bay and is pulled from Lake Geneva in a state of exhaustion. Zweig makes opposing worlds confront each other, the world of fighting and the world of an idyllic holiday resort, and depicts the fate of masses by means of the story of one individual. At the end only resignation and capitulation are left: Boris drowns himself in the lake; he is buried and a wooden cross is placed on his grave, ‘one of those small wooden crosses above a nameless fate with which our Europe is now covered from one end to the other’.

The situation of those returning home provided further material for many literary productions. These dealt with the trauma of the war in the backpack of memories, the estrangement from those who had remained at home, but also from the homeland itself, disorientation after the disintegration of the old orders, especially in Austria, where nothing was as it had been before. In his novel Die Flucht ohne Ende (The Flight Without End) (1927) – the subtitle describes it as a ‘Report’, Joseph Roth presented the wanderings of Franz Tunda, a soldier returning from the war, who, fleeing from captivity by the Russians, gets mixed up with the Russian revolution, then arrives in Austria after its collapse, later goes via Germany to Paris and is finally lost to the world in an existence marked by alienation and the absence of relationships, because ‘nobody in the world was as superfluous as he was.’

Shortly before the beginning of the first year of peace Kurt Tucholksy looked back on the war years in his poem Silvester (New Year’s Eve) (1918) and summed them up as follows:

"Four long years.

Time and again we again had to keep our heads down

and say nothing and just swallow.

Humans were military material and army supplies."

Tucholksky put an end to the war idyll, the courage of heroes and the spirit of comradeship; in his works the individual, the lyrical ‘I’ sits alone in front of a glass of wine and the picture of the abandoned Emperor, naming those responsible, settling accounts and warning: ‘Forget that, Always think of what the ancients sang!’

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Jünger, Ernst: In Stahlgewittern. Unter: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/34099/34099-h/34099-h.htm (19.06.2014)

Roth, Joseph: Die Flucht ohne Ende. Unter: http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/4268/1 (19.06.2014)

Zweig, Stefan: Episode am Genfer See. Unter: http://www.dhhh.eu/pdf/17StefanZweig.pdf (19.06.2014)

Tucholsky, Kurt: Silvester. Unter: http://www.textlog.de/tucholsky-silvester.html (19.06.2014)

Quotes:

"My fourth-form memories of Karl May ...": Jünger, Ernst: In Stahlgewittern. Unter: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/34099/34099-h/34099-h.htm (19.06.2014) (Translation)

"Jünger’s problem is a problem ...“: Müller, Heiner: Krieg ohne Schlacht. Leben in zwei Diktaturen, Köln 1992, 282 (Translation)

"one of those small wooden ...": Zweig, Stefan: Episode am Genfer See. Unter: http://www.dhhh.eu/pdf/17StefanZweig.pdf (19.06.2014) (Translation)

"nobody in the world ...": Roth, Joseph: Die Flucht ohne Ende. Unter: http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/4268/1 (19.06.2014) (Translation)

-

Chapters

- ‘Rabble of words’ – Writers in the War

- ‘An area to which only those who are (un)employed there have access.’

- The war after the war – reflection, homecoming and review

- ‘ … with deadly weapons, the golden plains’: Grodek as the legacy of the poet Georg Trakl

- ‘Guilt is always beyond doubt!’ Franz Kafka’s 'In der Strafkolonie' (In the Penal Colony)

- I did not want it: Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind)

- Anti-war literature as a bestseller: Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front)

- ‘What remained was a mutilated trunk that bled from every vein.’ Stefan Zweig and his "World of Yesterday"