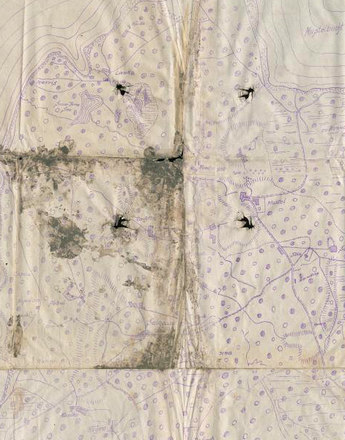

‘An area to which only those who are (un)employed there have access.’

The Imperial and Royal War Press Quarters (Kriegspressequartier/KPQ) was set up on 28 July 1914, the day of Austria-Hungary’s ultimatum to Serbia. Its purpose was to co-ordinate and direct military propaganda with specially written items for all media available at the time.

In the course of the war the KPQ grew to be a large and important instituion which employed several hundred artists and journalists. It had film, theatre and music sections, and a team of editors wrote propaganda texts for the media in Austria-Hungary and abroad. Also employed there was the Monarchy’s only woman war reporter, Alice Schalek, who achieved dubious fame as a result of being attacked by Karl Kraus in his journal Die Fackel (The Torch) – ‘The valiant Schalek is not afraid,’ and she appears in many scenes in Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind), where he stylizes her as the negative icon of what is in his view infamous war reporting.

The KPQ was popular with writers. Some of them tried to use it as a way to avoid military service, while others were forced to work there. At first the army command tried to employ eminent authors; occasionally young, still unknown writers like Leo Perutz or Egon Erwin Kisch did not succeed in getting there until they had been wounded. Authors who held the rank of an officer (for instance Robert Musil, Franz Karl Ginskey and Karl Zoglauer) were in a position to give commands and could thus get one or other of their fellow writers posted to the KPQ.

Those permanently employed by the KPQ included Alexander Roda Roda, Ludwig Hirschfeld and Ernst Klein, all of whom wrote for the Vienna daily Neue Freie Presse. Other authors, including Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Ludwig Ganghofer and Ludwig Thoma, were taken on only for single journeys to the front; afterwards it was possible for them to use the reports they had been commissioned to write for their own purposes.

The authors and journalists who worked for the KPQ did not always enjoy the highest prestige: they could not get rid of the reputation of being hacks. This was even more the case simply because the KPQ was based of all places in an inn in Rodaun (today part of Liesing, the 23rd district of Vienna, then a spa with a hot spring popular with summer visitors) that was a favourite place for Viennese high society to visit. Karl Kraus noted smugly in Die Fackel: ‘The press have been moved to Rodaun so that Herr von Hofmannsthal does not have so far to get to the front.’ In an earlier issue of his journal he had commented: ‘It is widely known that those members of the journalists’ trade who are voluntarily unfit for military service, together with a few mediocre but otherwise healthy master painters, were captured at the beginning of the war and locked up at a fenced off site that is known as the war press quarters, a place to which only those who are (un)employed there have access.’

The military command also sent prominent writers abroad on lecture tours. Franz Werfel, who was not assigned to the KPQ until 1917, travelled to Italy and then in 1918 to Switzerland, from where he was recalled earlier than planned after making unpatriotic statements – he advocated an end to the war. The writer Berta Zuckerkandl had heard Werfel and noted: ‘People are speculating whether on his return to Vienna he will be hanged or beheaded.’ In fact Werfel did not have to face any sanctions, probably in order to avoid a scandal.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Gruber, Hannes: „Die Wortemacher des Krieges“. Zur Rolle österreichischer Schriftsteller im Kriegspressequartier des Armeeoberkommandos 1914–1918, Graz Diplomarbeit 2012

Kalka, Joachim: Alice Schalek: Mutter aller Schlachtreporter. Gott, so ein Krieg! In: FAZ vom 28.3.2003. Unter:

http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/alice-schalek-mutter-aller-schlach... (17.05.2014)

Lustig Prean von Preansfeld, Karl: Aus den Geheimnissen des Kriegspressequartiers, in: Džambo, Jozo (Hrsg.): Musen an die Front. Schriftsteller und Künstler im Dienst der k. u. k. Kriegspropaganda 1914 – 1918. Begleitpublikation in 2 Bänden zur gleichnamigen Ausstellung, München 2003

Stiaßny-Baumgartner, Ilse: Roda Rodas Tätigkeit im Kriegspressequartier. Zur propagandistischen Arbeit österreichischer Schriftsteller im Ersten Weltkrieg, Wien Dissertation 1982

Quotes:

„‘The press have been moved …“: Kraus, Karl: Die nicht untergehen, in: Die Fackel von 4.1919 (F 508-513), 64f. (Translation)

„It is widely known …“: Kraus, Karl: Geteilte Ansichten über die Kriegsberichterstattung, in: Die Fackel vom 10.12.1915 (F 413-417), 33 (Translation)

„People are speculating whether …“: Zuckerkandl, Berta: Der Fall Franz Werfel, in: Mahler-Werfel, Alma: Mein Leben, Frankfurt 1960, 123 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- ‘Rabble of words’ – Writers in the War

- ‘An area to which only those who are (un)employed there have access.’

- The war after the war – reflection, homecoming and review

- ‘ … with deadly weapons, the golden plains’: Grodek as the legacy of the poet Georg Trakl

- ‘Guilt is always beyond doubt!’ Franz Kafka’s 'In der Strafkolonie' (In the Penal Colony)

- I did not want it: Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind)

- Anti-war literature as a bestseller: Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front)

- ‘What remained was a mutilated trunk that bled from every vein.’ Stefan Zweig and his "World of Yesterday"