‘ … with deadly weapons, the golden plains’: Grodek as the legacy of the poet Georg Trakl

In the evening the autumnal woods resound

With deadly weapons, the golden plains

And blue lakes, over them the sun

Rolls grimly away; the night envelops

Dying warriors, the savage lament

Of their smashed mouths.

But silently on the pastures

Red clouds gather, therein lives a raging god,

The spilled blood, the moonly cool;

All roads lead to black decay.

Under the golden branches of the night and stars

The shadow of the nurse sways through the silent grove,

To greet the spirits of the heroes, the bleeding heads;

And softly in the reeds sound the dark flutes of autumn.

O prouder grief! You iron altars,

Today the hot flame of the spirit is fed by an immense pain,

The unborn grandchildren.

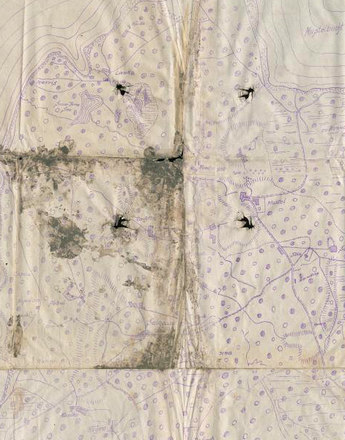

Grodek refers to the name of a place, today in Ukraine, where a battle with Russian troops ended in a devastating defeat for the Austro-Hungarian army. Because of his pharmaceutical knowledge – he had completed a three-year period of practical training at a dispensing chemist’s in Salzburg, Trakl volunteered to serve as a lieutenant in the medical corps. After the defeat at Grodek he had to take care of some ninety critically wounded men in a barn – without any medicines and anaesthetics. This task led to a complete mental breakdown and after attempting suicide he was admitted to a psychiatric clinic. During his stay there he wrote several poems, including Grodek. A few days later, in November 1914, he died of an overdose of cocaine.

Grodek is a typical example of Trakl’s poetry; in it motifs like those of night, autumn and death constantly recur. Trakl uses contrasts of sound and colour to show the opposition between unspoiled nature and the destruction caused by the war; this results in a state of hopelessness. There are countless interpretations of this poem, but in the end it is up to the individual reader to reflect critically on these images of nature and war and to derive from them the senselessness of the mass deaths on the fronts of the First World War.

The works of other Expressionists also put into words the apocalyptic feeling of the times. One of these was August Stramm; in his poem Sturmangriff (Assault) (1914) he describes the brutality of the war in highly artificial language by mutilating and deforming words.

While Georg Heym had already anticipated the horror in a visionary way in Der Krieg (The War) in 1911, many Expressionists went enthusiastically to war and celebrated it in their poetry, as Ernst Stadler did in his poem Der Aufbruch (The Departure) (1914). Irrespective of whether it is enthusiasm or shock that is expressed in their texts, many authors soon met with the same fate: in the first months of the war Stadler, Stramm and Trakl all paid for their euphoria with their lives.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Interpretation Grodek. Unter: http://lyrik.antikoerperchen.de/georg-trakl-grodek,textbearbeitung,71.html (19.06.2014)

Interpretation Sturmangriff. Unter: http://lyrik.antikoerperchen.de/august-stramm-sturmangriff,textbearbeitu... (19.06.2014)

Interpretation Der Aufbruch. Unter: http://lyrik.antikoerperchen.de/ernst-stadler-der-aufbruch,textbearbeitu... (19.06.2014)

-

Chapters

- ‘Rabble of words’ – Writers in the War

- ‘An area to which only those who are (un)employed there have access.’

- The war after the war – reflection, homecoming and review

- ‘ … with deadly weapons, the golden plains’: Grodek as the legacy of the poet Georg Trakl

- ‘Guilt is always beyond doubt!’ Franz Kafka’s 'In der Strafkolonie' (In the Penal Colony)

- I did not want it: Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind)

- Anti-war literature as a bestseller: Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front)

- ‘What remained was a mutilated trunk that bled from every vein.’ Stefan Zweig and his "World of Yesterday"