‘Guilt is always beyond doubt!’ Franz Kafka’s 'In der Strafkolonie' (In the Penal Colony)

Like other short stories Kafka’s In der Strafkolonie arose from a writing block, as the author found himself unable to continue with the end of Der Prozess (The Trial). Kafka wrote the story in October 1914, but it was not published until 1919, when it appeared in a one-off edition of 1,000 copies. The fantasies of guilt and punishment in Der Prozess are also to be found in In der Strafkolonie. In a key passage we read, ‘Guilt is always beyond doubt.’

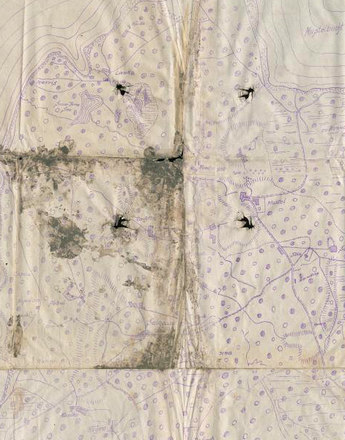

The theme of the story is a gruesome form of torture in wartime, a topic which had until then rarely been treated in literature. Reviewers criticized him, claiming that he had chosen the subject out of a desire for sensationalism, but he rejected this, referring to the violence of the present.

Kafka had read Le Jardin des Supplices (The Garden of Tortures) (1899) by the French journalist Octave Mirabeau. It was from there that he took the figure of the European traveller who, partly fascinated, partly repelled, is shown the sadistic penal practices of an island far away from civilisation. In the story the judicial system of a penal colony is presented. Every person accused, whether guilty or innocent, is tortured in a machine for twelve hours according to a strictly regulated procedure and is then killed. The sentence is not announced to the delinquent but is more or less inscribed on his body. Kafka describes the planned execution of a mutinous soldier who is being fixed onto the machine. His punishment is to have the command ‘Honour your superior’ tattooed on his body. Since the traveller does not seem to be convinced by the penal system, the officer releases the convicted prisoner, pulls out a sheet of paper from a leather folder with the new slogan ‘Be just!’ and places himself in the machine. The body of the officer is impaled and the machine, now out of control, lifts the dead officer and drops him into a ditch.

There are many interpretations of the story, which is often seen as anticipating the horrific deeds perpetrated in the war. However, Kafka himself made contradictory statements about the war. On the one hand there are some individual critical comments, but on the other there are his efforts to be accepted by the army in order to get to the front.

In 1916 Kafka read parts of this story in Munich during a series of lectures on literature at which Rilke was present. Some of the women listening apparently fainted because of the gruesome descriptions. Kurt Tucholsky reviewed the story in 1920, expressing the opinion, ‘This dream of Franz Kakfa’s is pitilessly harsh, cruelly objective and crystal-clear: In der Strafkolonie. … This slim book, a marvellous Drugulin print, is a masterpiece. Not since Michael Kohlhaas has a German novella been written which apparently suppresses every inner sympathy with such deliberate force and yet which is so thoroughly permeated with its author’s lifeblood.’

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Kafka, Franz: In der Strafkolonie. Unter: http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/156/1 (19.06.2014)

Stach, Reiner: Kafka. Die Jahre der Entscheidungen, 3. Auflage, Frankfurt am Main 2003, 536-563

Quotes:

„This dream of Franz Kakfa’s is …“: Tucholsky, Kurt: Rezension In der Strafkolonie. Unter: http://www.textlog.de/tucholsky-strafkolonie.html (19.06.2014) (Translation)

-

Chapters

- ‘Rabble of words’ – Writers in the War

- ‘An area to which only those who are (un)employed there have access.’

- The war after the war – reflection, homecoming and review

- ‘ … with deadly weapons, the golden plains’: Grodek as the legacy of the poet Georg Trakl

- ‘Guilt is always beyond doubt!’ Franz Kafka’s 'In der Strafkolonie' (In the Penal Colony)

- I did not want it: Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind)

- Anti-war literature as a bestseller: Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front)

- ‘What remained was a mutilated trunk that bled from every vein.’ Stefan Zweig and his "World of Yesterday"