‘Rabble of words’ – Writers in the War

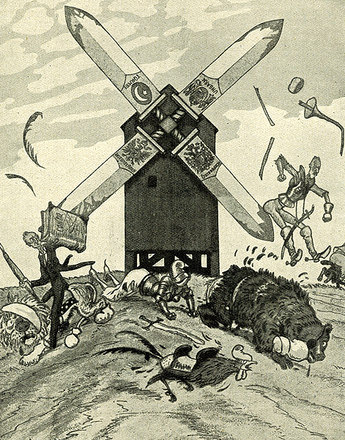

The beginning of the First World War released a wave of enthusiasm throughout Europe, especially among intellectuals and the middle classes, the like of which it is utterly impossible for us to understand nowadays. It was the writers who led the way in propaganda, their verbal attacks making an essential contribution in preparing the ground for the general mood of unthinking nationalism.

In February 1909 the Italian lawyer and writer Filippo Marinetti published the Futurist Manifesto in the French daily newspaper Le Figaro. In it he called in a provocatively radical manner for the destruction of all traditions and saw war as a suitable way of doing this: ‘We want to glorify war – the one and only way to cleanse the world, militarism, patriotism, the anarchists’ act of destruction, the beautiful ideas that kill, and contempt for women.’ Many artists – and writers too – were enthusiastic about the futurists’ credo, and some of them died for ‘the beautiful ideas’ on the battlefields of the First World War.

The literary mobilization began even before the war began. In 1910 the German writer Georg Heym noted in his diary: ‘It’s always the same, so boring, boring, boring. … Would that for once something would happen. .. Even if the only way were to start a war, it can be an unjust one. This peace is so rotten, oily and greasy like the sticky polish on old furniture.’

However, enthusiasm for the war did not reached its productive climax until shortly after the war had broken out. Eloquent combatants on all sides directed their national stereotypes against their respective opponents. The most popular German poem in the early stages of the war, Ernst Lissauer’s Hassgesang gegen England (Song of Hatred for England), became the epitome of the way poetry treated the war: ‘We love as one, we hate as one, we all have just one foe: England.’ At patriotic war evenings held in the Konzerthaus hall in Vienna Egon Friedell defamed, among others, the Italians as notorious traitors, the French as the barbarians of the West, and declaimed: ‘Japan is a plague of moths, peoples like the Serbs and the Montenegrins come straight from the zoo and are beyond the pale.’

In an outpouring of poetry vast quantities of poems were sent to newspapers, with the total for Germany being estimated at between 50,000 per day and 1.5 million just in August 1914. It was the intellectual élite who led the way, and the writers who were the most eloquent. The list of those who succumbed to the euphoric mood – in their writing and also in some cases as volunteers in war service, reads like a who’s who of the authors of the time, including Hermann Bahr, Alfred Döblin, Hermann Hesse, Gerhard Hauptmann, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Thomas Mann, Richard von Schaukal, Georg Trakl and Anton Wildgans. Alexander Roda Roda und Felix Salten worked as war reporters, while Robert Musil edited a newspaper for soldiers, and Stefan Zweig, Rainer Maria Rilke, Alfred Polgar, Felix Salten, Rudolf Hans Bartsch, Franz Karl Ginzkey and Franz Theodor Csokor did periods of service in the war archive, where they wrote propaganda, which Rilke ironically described as ‘doing the hair of heroes’.

On the opposing side the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle, exploited the stereotype of the ‘strong, deep Germany of old, the Germany of music and philosophy, against this monstrous modern aberration, the Germany of blood and iron’, while Rudyard Kipling, the author of the Jungle Book stories, already saw ‘the Huns’ standing at the gates.

Rarely – but there were such cases – a different tone was to be heard – like Anatol France or Romain Rolland, whose Au-dessus de la mêlée (Above the Melee) resulted in him being boycotted by bookshops and regarded with contempt by his fellow writers. Many opponents of the war fled to Switzerland, including Ernst Bloch and Walter Benjamin. Arthur Schnitzler remained silent, for which he deserves credit in view of the contemporary mood.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Heinemann, Julia et al.: Die Autoren und Bücher der deutschsprachigen Literatur zum 1. Weltkrieg 1914-1939. Ein bio-bibliographisches Handbuch, Göttingen 2008

Sauermann, Eberhard: Literarische Kriegsfürsorge. Österreichische Dichter und Publizisten im Ersten Weltkrieg [Literaturgeschichte in Studien und Quellen 4], Wien/Köln/Weimar 2000

Traub, Rainer: Der Krieg der Geister, in: Spiegel special (2004), 1, 26-30. Unter: http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/spiegelspecial/d-30300018.html (19.06.2014)

Weigel, Hans/Lukan, Walter/Peyfuss, Max D.: Jeder Schuss ein Russ. Jeder Stoss ein Franzos. Literarische und graphische Kriegspropaganda in Deutschland und Österreich 1914-1918, Wien 1983

Quotes:

„Rabble of words“: Zweig, Stefan: Briefe 1914-1918, Frankfurt am Main 1998, 110 (Translation)

„It’s always the same ...“: Heym, Georg: Dichtungen und Schriften. 3 Bände, Hamburg/München 1960, Bd. 3, 138f. (Translation)

Number of poems (estimate): quoted from: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn 2004, 190 (Fußnote 14) (Translation)

-

Chapters

- ‘Rabble of words’ – Writers in the War

- ‘An area to which only those who are (un)employed there have access.’

- The war after the war – reflection, homecoming and review

- ‘ … with deadly weapons, the golden plains’: Grodek as the legacy of the poet Georg Trakl

- ‘Guilt is always beyond doubt!’ Franz Kafka’s 'In der Strafkolonie' (In the Penal Colony)

- I did not want it: Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind)

- Anti-war literature as a bestseller: Im Westen nichts Neues (All Quiet on the Western Front)

- ‘What remained was a mutilated trunk that bled from every vein.’ Stefan Zweig and his "World of Yesterday"