The photographer as documentarian: the amateur's eye

-

“Buying a pig in Kudobince”, Leopold Wolf war photo album, 1915

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

“A sunny hour for cleaning and repairs on the Romanian front”, photo

Copyright: dform

-

Shot-down planes, Leopold Wolf war photo album, c. 1916

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

“Church in Kal”, extract from war photo album of Fritz Ortlieb, c. 1917

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien -

“A traitor”, Fritz Ortlieb war photo album, 1917

Copyright: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien/Fotografie: Angelika Spangel

Partner: Sammlung Frauennachlässe, Institut für Geschichte der Universität Wien

Although there was a lively trade with negatives and prints at the front, the majority of amateur photographers were not thinking of a specific recipient but instead photographed what seemed to them to be of documentary value. They recorded what appeared to reflect their experiences of the war. In this way, their photographs contradicted the official image of the war as published in newspapers and magazines.

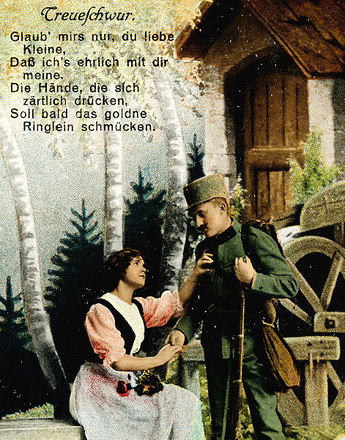

In contrast to those photographs that were taken with the intention of creating propaganda and glorifying war, amateurs were attracted by other motifs. Photographs were primarily taken to remind the soldiers of the war, recording what constituted 'their war'. With an obsession for detail, they documented scenes of everyday life, violence and destruction. They were guided by a reliance on the documentary power of the camera and the hope of making individual experiences visible. At the same time, the permanent threat and mental stress made them keenly aware of the transience of life. Thus each photograph was also a sign of survival that was sent home in the form of a picture postcard.

In addition, the soldiers wanted to communicate a picture of life at the front to those at home. Brief comments ("Here you can see…") written on the backs of the photos are evidence of the hope that the objects depicted could speak for themselves and help to bridge the distance to the family members far away. Since many of the experiences at the front could not be associated with comparable experiences in civilian life, the assumed authenticity of the photograph was intended to represent the unspeakable and give it a voice. Conversely, photos from home were intended to document and communicate the children growing up, the well-being of the family members and the like. Photography was meant to communicate between the two worlds – the front and home – and to build a communicative bridge between the two worlds of experience.

The pictorial world of the soldier snapshooters comprised above all two groups of motifs. Firstly, they were a record of the new and the unknown while at the same time giving it a coating of 'normality'. The camera showed Christmas being celebrated, soldiers cooking and cleaning, setting up positions and building a base. War landscapes, equipment and weapons were photographed and preserved for the future. Photographing the soldiers' everyday life in the usual alternation of work and leisure created an analogy to everyday life at home.

Secondly, the amateur photographic eye captured the violence and threats to which they were permanently exposed. Off the beaten track of the established habits of seeing, the soldiers documented attacks on the civilian population, showed death and brutality, mass firing squads and executions unrestrained by any taboo or censorship. Looking through the camera created distance, putting the photographing soldier on the other side, making them into victors. These unofficial images were rarely seen in the illustrated press and only rarely found their way into the archives.

Translation: David Wright

Holzer, Anton (Hrsg.): Mit der Kamera bewaffnet. Krieg und Fotografie, Marburg 2003Li

Hüppauf, Bernd: Fotografie im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Spilker, Rolf/Ulrich, Bernd (Hrsg.): Der Tod als Maschinist. Der industrialisierte Krieg 1914–1918. Eine Ausstellung des Museums Industriekultur Osnabrück im Rahmen des Jubiläums „350 Jahre Westfälischer Friede“ 17. Mai – 23. August 1998, Osnabrück 1998, 108-123

Starl, Timm: Knipser. Die Bildgeschichte der privaten Fotografie in Deutschland und Österreich 1880 bis 1980, München 1995

-

Chapters

- Public relations in the First World War: the state organisation for war reporting

- The WPH Photograph Office

- "Embedded photography": war photographers as part of military logistics

- Photography as a weapon: reconnaissance, surveying, documentation

- Who photographed the war? Snapshooters, amateurs, front tourists

- The canon of images of the First World War as reflected in the illustrated press

- The photographer as documentarian: the amateur's eye

- World War photography between traditional pictorial conventions and the Modern