In the second half of the war, the focus of war reporting shifted to the medium of photography. The aim behind the WPH's deployment of official war photographers was to direct the public's visual perception of the war.

At the start of the war, the War Press Headquarters (WPH) concentrated the official representation of the war on written reports and classical military and battle painting. It was only when Colonel Wilhelm Eisner-Bubnas was appointed director in spring 1917 that an awareness developed for the manipulative power of photography. The WPH gradually shifted to creating structures for the government control of photographs and to placing pictorial propaganda at the centre of opinion-forming activities. The Photograph Office became the central department for pictorial propaganda, commissioning, censoring and processing the official pictorial reporting.

The War Press Headquarters' strategy was to extend its monopoly position to the pictorial representation of the war. The production of images was to be encouraged, but at the same time strictly monitored and regulated so that private agencies practically ceased to be source of supply for the illustrated press. This media concentration under government pressure ensured that the pictures published during the years of the war largely corresponded with the demands of government propaganda.

Experienced press photographers from established newspapers and professional photographers were recruited and sent to the front as officially accredited war photographers. For them, membership of the War Press Headquarters was not only a step up in their careers but also protection against having to serve at the front. In part they could continue to work for the newspapers and photo agencies, but they were primarily subject to the command hierarchy of the WPH.

In the war zones, press photographers were co-ordinated in what were known as Photo Offices and entrusted with the task of making photos both for military purposes and for the press and propaganda. The war was to be presented from its heroic side: successful raids, defeated opponents and the challenges of everyday soldier life were skilfully staged. Depending on where they were deployed, the war photographers were expected to supply between five and sixty photos a month, but some also delivered hundreds of photographs from the battles zones. However, only very few succeeded in publishing their photos under their own names, and most photographers remained anonymous.

The War Press Headquarters' Photograph Office systematically collected the photographs, censored pictures unsuitable for propaganda purposes and supplied the domestic and foreign press with pictorial material. In addition, the photos were shown in exhibitions, used as advertising material and passed on to schools and publishers.

Translation: David Wright

Holzer, Anton: Die andere Front. Fotografie und Propaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg, Darmstadt 2007

Paul, Gerhard: Bilder des Krieges – Krieg der Bilder. Die Visualisierung des modernen Krieges, München 2004

-

Chapters

- Public relations in the First World War: the state organisation for war reporting

- The WPH Photograph Office

- "Embedded photography": war photographers as part of military logistics

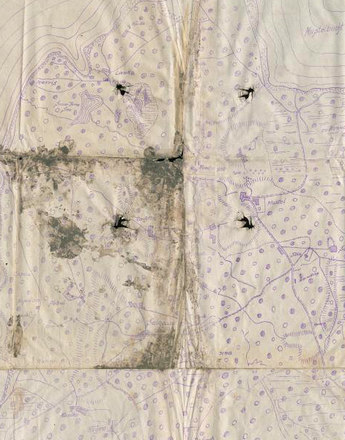

- Photography as a weapon: reconnaissance, surveying, documentation

- Who photographed the war? Snapshooters, amateurs, front tourists

- The canon of images of the First World War as reflected in the illustrated press

- The photographer as documentarian: the amateur's eye

- World War photography between traditional pictorial conventions and the Modern