Photography as a weapon: reconnaissance, surveying, documentation

Technical achievements at the beginning of the 20th century allowed the use of aerial photography as a strategic element in warfare. The aircraft became a tool for seeing, the camera a weapon. Aerial reconnaissance created new space for warfare, providing a previously unobtainable view over the war zones.

It was in the First World War that aerial photography was first used intensively by the military as a source of information. Decades previously, there had already been attempts to make visual recordings from a great height in order to have a wider strategic overview. Draughtsmen were sent up in tethered balloons, cameras attached to balloons and even doves were fitted with recording devices. But it was only a few years before the First World War, on 23 October 1911, that the first reconnaissance aircraft equipped with cameras and measuring devices took off in Italy to investigate the road from Tripoli to Azizia from the air during the war against the Ottoman Empire.

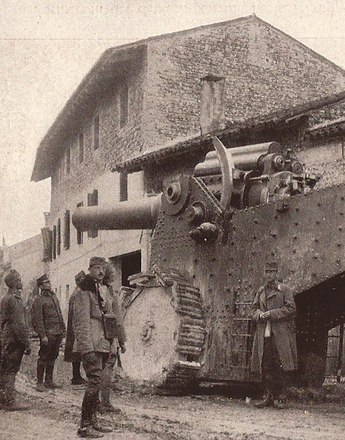

Photography was then used systematically in the First World War. Important developments of previous years, such as shorter shutter times, more sensitive lenses and refined photographic reproduction techniques meant that detailed information from afar could be recorded. The combination of flight and photography extended the range of the visible. Enemy troops could be investigated using modern photography, photos of weapons systems were used for training soldiers and ground photography supported the artillery. The reconnaissance and survey photos were taken by specialists recruited from the Imperial and Royal Military Geographical Institute.

As intelligence sources, however, the aerial photographs first needed to be interpreted – the pictures supplied were too abstract and out of focus. By using indexical symbols, codes were developed to allow clear knowledge to be read out of the pictures. Thus the information was reduced to a few topographical characteristics: a triangle meant a depot, a circle with a dot a mortar position. In this way, the General Staff succeeded in overcoming the distortions of the medium and combining the illustrations to show the course of entire fronts. The maps obtained in this way were distributed throughout the entire command hierarchy.

The value of the aerial photographs lay above all in the fact that information could be obtained about military activity over large distances. This became necessary because military action had disappeared from eyelevel as a result of aerial and trench warfare, new weapon technology and changes in the way war was fought. Using aerial photography brought war back into view.

Translation: David Wright

Holzer, Anton: Die andere Front. Fotografie und Propaganda im Ersten Weltkrieg, Darmstadt 2007

Holzer, Anton (Hrsg.), Mit der Kamera bewaffnet. Krieg und Fotografie, Marburg 2003

Paul, Gerhard: Bilder des Krieges – Krieg der Bilder. Die Visualisierung des modernen Krieges, München 2004

Sekula, Allan: Das instrumentalisierte Bild. Streichen im Krieg, in: Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie (1992), 45/46, 55-75

Siegert, Bernhard: Luftwaffe Fotografie. Luftkrieg als Bildverarbeitungssystem 1911-1921, in: Fotogeschichte. Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie (1992), 45/46, 41-54

-

Chapters

- Public relations in the First World War: the state organisation for war reporting

- The WPH Photograph Office

- "Embedded photography": war photographers as part of military logistics

- Photography as a weapon: reconnaissance, surveying, documentation

- Who photographed the war? Snapshooters, amateurs, front tourists

- The canon of images of the First World War as reflected in the illustrated press

- The photographer as documentarian: the amateur's eye

- World War photography between traditional pictorial conventions and the Modern