-

“The huge toy”, caricature, 1990

Copyright: IMAGNO/Austrian Archives

-

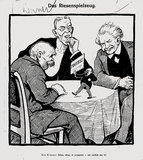

“In St Germain”, caricature from the newspaper Arbeiterwille of 20 January 1919

Copyright: ÖNB/ANNO

Partner: Austrian National Library -

Chancellor Karl Renner on the way to signing the Peace Treaty of St Germain, photo from Das Interessante Blatt, issue of 18 September 1919

Copyright: ÖNB/ANNO

Partner: Austrian National Library -

The Provisional National Assembly of German Austria on 21 October 1918 in the Lower Austrian Landhaus in Vienna, photo from Das Interessante Blatt, issue of 31 October 1918

Copyright: ÖNB/ANNO

Partner: Austrian National Library -

Max Frey: The proclamation of the Republic from the balcony of the Lower Austrian parliament in Vienna’s Herrengasse on 30 October 1918, painting, 1918

Copyright: Heeresgeschichtliches Museum, Wien

Partner: Heeresgeschichtliches Museum -

The members of the first government of German-Austria in March 1919, photo from Das Interessante Blatt, issue of 27 March 1919

Copyright: ÖNB/ANNO

Partner: Austrian National Library

The aim of the peace conferences held in the suburbs of Paris between January 1919 and August 1920 was to create a new international order.

The peace concluded with the German Empire, German-Austria, Bulgaria, Hungary and Turkey was regulated by the treaties of Versailles, Saint-Germain, Neuilly, Trianon and Sèvres respectively, and these also laid down the post-war order. The peace negotiations were in essence based on the ‘Fourteen Points’ of the American president Woodrow Wilson, in which he called, among other things, for the establishment of a League of Nations as well as self-determination of the peoples. The tenth of these points states:

The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development.

According to Wilson, the individual ethnic groups or nationalities were, if they so wished, in future to have their own states. The hopes of the defeated powers to claim this right of self-determination also for themselves were, however, not fulfilled. The Allies saw the Republic of German-Austria as the direct successor of the Danube Monarchy which had been responsible for the outbreak of the First World War, which is why the small newly created state was given no say in the negotiations and had to accept in their entirety the conditions imposed on it.

Like the German Empire, Austria had to accept the loss of large swathes of territory and could not push through its demand that all German speakers of the former Habsburg monarchy should be brought together in the newly founded republic. While the south of Carinthia and Burgenland fell to Austria after a period of many conflicts, other (partly) German-speaking areas were lost – including South Tyrol, the Kanaltal/Val Canale, South Styria, the Miess/Mežica valley to the south of the Karawanken mountains, and parts of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia. As a result of the peace negotiations in Paris, only 6.5 million out of a total ten million German-speaking inhabitants remained in Austria. It was no longer allowed to use the name German-Austria. In addition any union with Germany was forbidden. This was why the treaty between Austria and the twenty-seven allied and associated powers signed by Chancellor Karl Renner in the chateau of Saint-Germain on 10 September 1919 tended to be seen as a ‘dictated peace’, or, in the exaggerated formulation of the then head of state Karl Seitz, as a ‘totally destructive peace’.

However, the frontiers which were laid down in the Paris peace treaties for the states of Central and Eastern Europe took the claims of the individual ethnic groups into consideration only to a limited extent. There was no long-term solution to the problems of minorities and nationalities. For example, in the republic of Czechoslovakia 43% of the population were Czechs and 22% Slovaks, while 23% were Germans, 5% Hungarians, 3% Ukrainians and 4% Jews.

The situation was made worse because in many cases the First World War had led to an increase in nationalism.

Translation: Leigh Bailey

Berger, Peter: Kurze Geschichte Österreichs im 20. Jahrhundert, 2. Auflage, Wien 2008

Goldinger, Walter/Binder, Dieter A.: Geschichte der Republik Österreich 1918-1938, München 1992

Haas, Hanns: Österreich im System der Pariser Vororteverträge, in: Tálos, Emmerich/Dachs, Herbert/Hanisch, Ernst/Staudinger, Anton (Hrsg.): Handbuch des politischen Systems Österreichs. Erste Republik 1918-1933, Wien 1995, 665-693

Hanisch, Ernst: Österreichische Geschichte 1890-1990. Der lange Schatten des Staates. Österreichische Gesellschaftsgeschichte im 20. Jahrhundert, Wien 1994

Mikoletzky, Lorenz: Saint-Germain und Karl Renner. Eine Republik wird diktiert, in: Konrad, Helmut/Maderthaner, Wolfgang (Hrsg.): Das Werden der Ersten Republik … der Rest ist Österreich. Bd. I, Wien 2008, 179-186

Möller, Horst: Europa zwischen den Weltkriegen, München 1998

Sandgruber, Roman: Das 20. Jahrhundert, Wien 2003

Suppan, Arnold: Österreich und seine Nachbarn 1918-1938, in: Karner, Stefan/Mikoletzky, Lorenz (Hrsg.): Österreich. 90 Jahre Republik. Beitragsband der Ausstellung im Parlament, Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen 2008, 499-512

Vocelka, Karl: Geschichte Österreichs. Kultur – Gesellschaft – Politik, 3. Auflage, Graz/Wien/Köln 2002

14-Punkte-Programm von US-Präsident Woodrow Wilson. Unter: http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/dokumente/14punkte/ (22.04.2013)

Quotes:

"The peoples of Austria-Hungary ...“: Woodrow Wilson, quoted from: Website des Deutschen Historischen Museums. Unter: http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/dokumente/14punkte/ (22.04.2013), (Translation)

-

Chapters

- The High Price of Peace

- Tyrol Is Divided

- Burgenland Is Gained

- The defensive campaign in Carinthia and the plebiscite on 10 October 1920

- Losing Southern Styria

- Fixing the Northern Frontier

- Austrian Federal Province or Swiss Canton?

- Austrian attempts to unite with Germany from the founding of the republic to the referendums in Tyrol and Salzburg in 1921