Since the turn of the century there had been a marked drop in the birth rate throughout central Europe. Because of the deteriorating supply situation during the war, the number of births dwindled even further between 1914 and 1918.

In the future German Austria, the annual birth rate dropped from around 250,000 before the war to 140,000 in 1918. In 1913, there were 37,367 births in Vienna; in 1918 the level had decreased to just 19,257. In the German Empire, there were 2 million fewer births during the war.

The declining birth rate in all war societies was a result not just of the separation of partners but also of the economic situation. Because of the difficult supply situation, a pregnancy was seen as an additional burden, and many couples therefore attempted to avoid it.

With the men conscripted, the responsibility for feeding and looking after the family shifted to the women. Not only did they have to replace the absent labour and take on jobs hitherto performed by men, they also had to acquire food. The hour-long queues in front of grocery stores were particularly tedious. The health of many women suffered considerably, and they were often too weak to bring a child into the world. While the number of pregnancies declined, there was also a marked increase in Vienna in miscarriages and infant mortality.

A welfare worker in Vienna described the appalling situation for mothers as follows:

“Women are allowed only a few days rest after giving birth. Then they have to leave and stand in line again for food. […] There is a regulation that pregnant and breastfeeding women don’t have to stand in line, but if they insist on it, people just say ‘we don’t care about regulations from the council or health insurance.’ That’s what maternity and child welfare are like in practice.”

Although extramarital sexual relations were more frequent, the number of illegitimate births declined even more than legitimate ones. This is a sign of the increasing use of contraceptives and of the large number of abortions. Amongst the working class, the commonest form of contraception was coitus interruptus (referred to as “being careful”) and postcoital vaginal douching. Reliable condoms were often too expensive, and caps and diaphragms required visits to the doctor, which also cost money.

In spite of the strict abortion laws in Austria and Germany with punishments of up to five years’ imprisonment, abortions were common. Surveys at the time indicate that women saw nothing reprehensible about it, but regarded it rather as a legitimate method of preventing a difficult situation from becoming even worse. Apart from conventional abortifacient agents like ergot or savin juniper, chemicals and instruments were also used. Injuries and infections were a frequent consequence, which meant that for many women abortion became a life-threatening undertaking.

Translation: Nick Somers

Augeneder, Sigrid: Arbeiterinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen proletarischer Frauen in Österreich, Wien 1987

Daniel, Ute: Frauen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn et al. 2009, 116-134

Daniel, Ute: Arbeiterfrauen in der Kriegsgesellschaft. Beruf, Familie und Politik im Ersten Weltkrieg, Göttingen 1989

Eder, Franz X.: Kultur der Begierde. Eine Geschichte der Sexualität, 2. Auflage, München 2009

Kundrus, Birthe: Kriegerfrauen. Familienpolitik und Geschlechterverhältnisse im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg, Hamburg 1995

Quotes:

“Women are allowed ...": Fürsorgerin der Gemeinde Wien, in: Arbeiterinnen-Zeitung, Nr. 24 vom 27. November 1917, 5, quoted from: Augeneder, Sigrid: Arbeiterinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen proletarischer Frauen in Österreich, Wien 1987, 154 (Translation)

-

Chapters

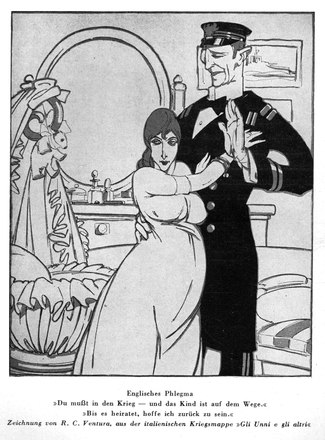

- Separation of husbands and wives and sexual mobility in the First World War

- Dwindling birth rates during the First World War

- "Mobilisation of the cradle"

- State control and social stigma

- Abstinence and satisfaction of needs

- Combatting venereal diseases in the Austro-Hungarian army

- “Resist from the outset”

- Sexual relief for soldiers

- Prevention or punishment

- Sexual assault in the First World War

- Sexual violence in Allied war propaganda