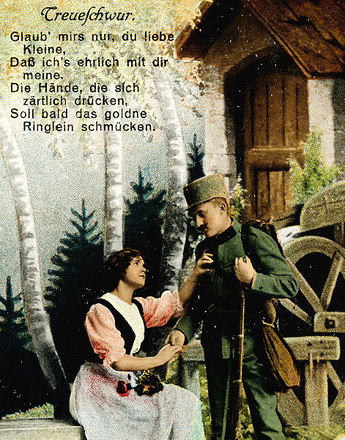

With the outbreak of war, complementary gender roles were reinforced. The ideal of the active fighting soldier was complemented by the image of the passive, self-sacrificing mother. These models meant that extramarital sexual relations by women were socially stigmatised.

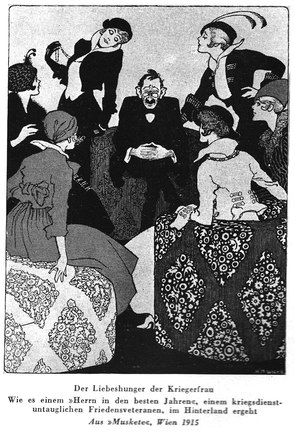

This idea of polar gender roles had its roots in the bourgeois double standards and their wartime version. While the sexual mobility of the troops was widely accepted, all forms of female sexuality outside of marriage were roundly condemned. Female sexual behaviour at home was a focus of national interest not only in terms of increasing the population. It was widely believed that the fighting morale of the soldiers depended to a large extent on the sexual fidelity of the wives and partners back home.

The result was the increased criminalisation of female sexuality. Extramarital sexual relations by women were stigmatised as “covert prostitution” – even though there was no money involved. According to a report by the office of the governor of Innsbruck in March 1918, covert prostitutes were defined as “women who had sexual relations with different men, […] even if they obtained no material gain from them.”

The increased sexual mobility of women endangered the stability of the perceived gender roles. Unfaithful women did not conform to the wartime propaganda, which stated that the troops were also going to war to protect their self-sacrificing and caring wives. This provoked national concern and a series of initiatives to control female sexual behaviour.

The departments responsible for public morality in Austria and Germany intensified their control not only of registered prostitutes but also of women suspected of it. Doctors and health politicians repeatedly lamented the inefficient control of “covert” prostitution by these departments. The Austrian military therefore suggested that women working in the hotel and restaurant industry, who could possibly spread venereal diseases, should be forced to undergo regular examinations. The massive public protest prevented this measure from being implemented.

Women who had a (sexual) relationship with a prisoner of war were ostracised by society and also subject to criminal prosecution. According to the Imperial Regulation of 23 May 1915, women in Austria were forbidden from “any communication with prisoners of war that was not strictly necessary for the purpose of work or duty”, subject to criminal prosecution for violations. The punishments were also to be announced in the residential communities in which the women lived. Members of the “Ohrfeigen-Liga” in Innsbruck endeavoured to ensure that women who entered into a relationship with a prisoner of war were denounced and publicly flogged.

This public discrediting was a further means of controlling the sexual behaviour of war wives. The social defamation of soldiers’ wives whose husbands at the front were able to gain sexual gratification behind the lines was an example of the wartime version of bourgeois double morality.

Translation: Nick Somers

Daniel, Ute: Arbeiterfrauen in der Kriegsgesellschaft. Beruf, Familie und Politik im Ersten Weltkrieg, Göttingen 1989

Daniel, Ute: Frauen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn et al. 2009, 116-134

Hirschfeld, Magnus/Gaspar, Andreas: Sittengeschichte des Ersten Weltkrieges, 2. Auflage, Hanau am Main 1966

Kundrus, Birthe: Kriegerfrauen. Familienpolitik und Geschlechterverhältnisse im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg, Hamburg 1995

Peters, Hubert: Über Schutzmaßregeln für die Frauenwelt in hygienischer und sozialrechtlicher Beziehung, Wien 1918

Überegger, Oswald: Krieg als sexuelle Zäsur? Sexualmoral und Geschlechterstereotypen im kriegsgesellschaftlichen Diskurs über die Geschlechtskrankheiten. Kulturgeschichtliche Annäherungen, in: Kuprian, Hermann J. W./Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung. La Grande Guerra nell’arco alpino. Esperienze e memoria, Innsbruck 2006, 351-366

Quotes:

“women who had sexual …“: Statthalterei-Rundschreiben an die Bezirkshauptmannschaften, 7.3.1918, quoted from: Überegger, Oswald: Krieg als sexuelle Zäsur? Sexualmoral und Geschlechterstereotypen im kriegsgesellschaftlichen Diskurs über die Geschlechtskrankheiten. Kulturgeschichtliche Annäherungen, in: Kuprian, Hermann J. W./Überegger, Oswald (Hrsg.): Der Erste Weltkrieg im Alpenraum. Erfahrung, Deutung, Erinnerung. La Grande Guerra nell’arco alpino. Esperienze e memoria, Innsbruck 2006, 359 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Separation of husbands and wives and sexual mobility in the First World War

- Dwindling birth rates during the First World War

- "Mobilisation of the cradle"

- State control and social stigma

- Abstinence and satisfaction of needs

- Combatting venereal diseases in the Austro-Hungarian army

- “Resist from the outset”

- Sexual relief for soldiers

- Prevention or punishment

- Sexual assault in the First World War

- Sexual violence in Allied war propaganda