The birth rate dropped considerably between 1914 and 1918. In view of the loss of life caused by the war, the reproductive behaviour of the population became a matter of national interest.

The belligerent states were very concerned about the dwindling birth rate, as it threatened the defensive capability and military strength of the nation. Increasing the number of children became a national project. All of the societies at war introduced pronatal measures and improved maternity and infant welfare.

In practically all of the belligerent countries, unmarried women made pregnant by a soldier received a family allowance from the state. In Germany the Reich Maternity Welfare Regulation was adopted as early as December 1914. Women whose husbands had been conscripted and who had prior health insurance would be provided with financial support to help cover the delivery costs. After 1915, an illegitimate child whose father had been killed in the war was entitled to an allowance. Other measures included an increase in the number of nurseries, kindergartens and childcare centres.

Women who breastfed their children also received a special allowance. From 1916, the local health insurance office in the Vienna district of Floridsdorf gave a breastfeeding allowance to mothers who agreed to breastfeed their babies for at least eight weeks and who didn’t work during that time. The city of Vienna supported needy pregnant woman and mothers by paying a weekly allowance and distributing milk and food coupons. Following a reform of the Health Insurance Law in 1917, the government of Cisleithania extended the maternity allowance from four to six weeks and offered breastfeeding mothers additional assistance.

Apart from measures by the state, private welfare initiatives also provided mothers with support to reduce infant mortality. In early 1915 the War Sponsorship scheme was launched in Vienna, by which wealthy citizens could sponsor the children of needy mothers by giving them a monthly allowance of 12–14 krone. By the end of the war, some 29,100 children had been sponsored in this way.

The initial appeal by the War Sponsorship Committee emphasised the importance of this campaign for the population:

“At a time when thousands of our men are serving on the battlefield, it is more than ever a patriotic and heart-felt duty to protect children; the coming generation will fill the gaps being created in our midst on account of the war.”

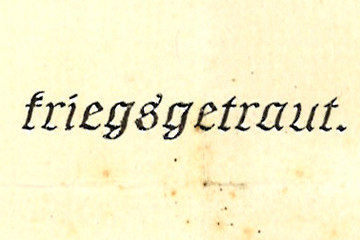

The variety of private and state measures to promote births could well be described as a “mobilisation of the cradle”, as a book by Ferdinand-Antonin Vuillermet published in 1917 was called. In the end, however, they were unable to improve the dwindling birth rates.

Translation: Nick Somers

Augeneder, Sigrid: Arbeiterinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen proletarischer Frauen in Österreich, Wien 1987

Daniel, Ute: Frauen, in: Hirschfeld, Gerhard/Krumeich, Gerd/Renz, Irina (Hrsg.): Enzyklopädie Erster Weltkrieg, Paderborn et al. 2009, 116-134

Eder, Franz X.: Kultur der Begierde. Eine Geschichte der Sexualität, 2. Auflage, München 2009

Kundrus, Birthe: Kriegerfrauen. Familienpolitik und Geschlechterverhältnisse im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg, Hamburg 1995

Sauerteig, Lutz: Sex, Medicine and Morality during the First World War, in: Cooter, Roger/Harrison, Mark/Sturdy, Steve (Hrsg.): War, Medicine and Modernity, Stroud 1998, 167-188

Quotes:

“At a time when thousands ...": Gründungsaufruf des Kuratoriums für Kriegspatenschaft, in: Zeitschrift für Kinderschutz und Jugendfürsorge, (1915), 1, 16, quoted from: Augeneder, Sigrid: Arbeiterinnen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Lebens- und Arbeitsbedingungen proletarischer Frauen in Österreich, Wien 1987, 157 (Translation)

"Mobilisation of the cradle": Vuillermet, Ferdinand-Antonin: La mobilisation des berceaux, Lethielleux, 1917 (Translation)

-

Chapters

- Separation of husbands and wives and sexual mobility in the First World War

- Dwindling birth rates during the First World War

- "Mobilisation of the cradle"

- State control and social stigma

- Abstinence and satisfaction of needs

- Combatting venereal diseases in the Austro-Hungarian army

- “Resist from the outset”

- Sexual relief for soldiers

- Prevention or punishment

- Sexual assault in the First World War

- Sexual violence in Allied war propaganda