-

Story The End of the War

The disintegration of the Habsburg Monarchy – Part I: On the road to self-determination

-

The founding fathers of Czechoslovakia in front of the Jan Hus Monument in Prague, postcard, 1918/19

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur- und Betriebsges.m.b.H. / Objekt aus der Sammlung Dr. Lukan

-

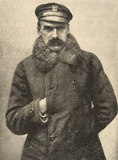

Józef Piłsudski, portrait photograph, around 1914

Copyright: Schloß Schönbrunn Kultur-und Betriebsges.m.b.H./Fotograf: Alexander E. Koller

-

“The Serbs in Ljubljana: Reception of the Serbian troops by Mayor Hribar”, newspaper photo from Das Interessante Blatt, issue of 28 November 1918

Copyright: ÖNB/ANNO

Partner: Austrian National Library

For the non-German and non-Magyar peoples the incipient disintegration of the Monarchy opened up new prospects for the future.

The autumn of 1918 saw the leading political representatives of the ‘other nationalities’ change their attitude towards the Monarchy as the state within which they might or might not pursue their national existence. The slogan of ‘self-determination’ was their answer to the unwillingness of the German Austrians and the Magyars to agree to a radical reshaping of the Monarchy. Karl’s manifesto of 16 October 1918 ‘To My faithful Austrian peoples’ was a half-hearted attempt that came too late – and his offer of federalization fell on deaf ears.

A characteristic example of the change in attitudes towards the Habsburg Monarchy is provided by the development amongst the Czechs, who were the third largest national group in the Monarchy and had the most highly developed emancipation movement, within which two different lines of action were pursued.

Firstly, Czech political émigrés had been lobbying for their national cause with the Western Powers since the beginning of the war, with the goal of an independent state having very early become a realistic option. This line of political activity came to a head on 26 September 1918 with the establishment of a Czechoslovakian National Council and the proclamation of an independent Czechoslovakia, which was shortly afterwards recognized by the Allies as a belligerent state.

Secondly, the Czech political representatives who had stayed at home and who were organized in a Czech national committee in the Reichsrat for a long time fought shy of the idea of complete secession from the Habsburg Monarchy. They preferred to pursue a solution on federal lines and considered the pro-Austrian form of Czech activism a viable option.

Vienna’s determination to preserve the status quo resulted in a perceptible change in attitudes on the Czech political scene. Within a period of only a few weeks all the Czech political parties swung around to the anti-Austrian position, with the émigrés taking over the political leadership. The clear imminence of Austria-Hungary’s capitulation led to a rapid sequence of events that culminated on 28 October in Prague with the declaration of independence. The fait accompli was confirmed on 30 October when Slovak representatives who had hitherto only been peripherally involved ratified the foundation of Czechoslovakia in the Declaration of Svätý Martin named after the town where the resolution was made.

Developments followed a similar course for the southern Slav nationalities of the Habsburg Monarchy, who faced an additional obstacle in the form of disagreements over their united future – in particular with respect to the Serbian claim to the leadership. On 6 October 1918, as a result of the uncompromising positions still being held by the Austrian and Hungarian governments, the southern Slav deputies of the Austrian Reichsrat and of the Hungarian parliament assembled in Zagreb as the National Council of the Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and declared themselves the representatives of the southern Slavs within the Habsburg Monarchy. In the course of the continued disintegration of the Monarchy agreement was finally given to the formation of a unified state under Serbian leadership, which led to the proclamation of the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the ‘SHS State’) on 1 December 1918.

The Poles found themselves in a special situation in that although all sides agreed that a Polish state would be part of the post-war order, opinions differed on the geographical extent of the new state and on its degree of independence. The interests of the Poles were defended by a number of different national representative bodies. The Polish National Committee in exile in Paris had in the meantime been recognized by the Western Powers as representing a belligerent state. At home, on the other hand, a Polish Council of Government operating under the control of the Central Powers was also seeking to make progress with plans for an independent Poland, which made coordination difficult. Following the proclamation of the new Polish state on 7 October 1918, three governments were formed (Warsaw, Lublin, Cracow). Finally, in November general recognition was given to the Warsaw government under Józef Piłsudski.

Translation: Peter John Nicholson

Bihl, Wolfdieter: Der Erste Weltkrieg 1914–1918. Chronik – Daten – Fakten, Wien/Köln/Weimar 2010

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Böhmens. Von der slavischen Landnahme bis ins 20. Jahrhundert, München 1987

Hoensch, Jörg K.: Geschichte Polens. (3. Auflage), Stuttgart 1998

Hösch, Edgar: Geschichte der Balkanländer. Von der Frühzeit bis zur Gegenwart, München 1999

Rauchensteiner, Manfried: Der Erste Weltkrieg und das Ende der Habsburgermonarchie 1914–1918, Wien u. a. 2013

Štih, Peter/Simoniti, Vasko/Vodopivec, Peter: Slowenische Geschichte. Gesellschaft – Politik – Kultur, Graz 2008

-

Chapters

- The course of the war 1917–1918: Face-to-face with imminent downfall

- The situation in the hinterland

- Apathy and resistance – The mood of the people

- The Sixtus Affair: A major diplomatic débacle

- A programme for world peace – President Wilson’s Fourteen Points

- ‘To My faithful Austrian peoples’ – Emperor Karl’s manifesto

- The collapse

- The disintegration of the Habsburg Monarchy – Part I: On the road to self-determination

- The disintegration of the Habsburg Monarchy – Part II: The situation in Vienna and Budapest

- The last days of the Monarchy